El Orcoquisac

In the 1720s, French traders began visiting the Galveston Bay area to trade with the Akokisa (Orcoquisa) and Bidai Indians. The French came both by boat from New Orleans and overland from Nacogdoches to exchange European goods for furs, skins, and bear grease. In May 1754, trader Joseph Blancpain and several other Frenchmen set up a permanent trading post near the east bank of the Trinity River, about 8 kilometers upstream from Trinity Bay.

Word of the trading post soon reached Spanish authorities, who became alarmed by the encroachment of the French into the eastern edge of their territory. In September they dispatched a military force of 25 soldiers from Los Adaes under the command of Lieutenant Marcos Ruiz. The expedition was bolstered along the way by Akokisa and Bidai Indians who were promised the spoils from the trading post in return for their assistance in locating it. In October, the expedition reached the trading post and arrested the Frenchmen for trespassing on Spanish territory. The Spanish took the Frenchmen to Mexico City and allowed the Akokisa and Bidai to take their goods. Under interrogation, Blancpain told the Spanish authorities that the trading post was intended to be the first stage in a French settlement.

Spanish Presence Established

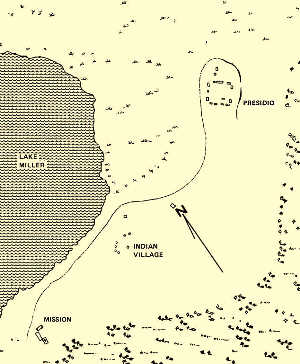

Determined to prevent a French settlement of the area, the Spanish established the Presidio of San Augustín de Ahumada in July 1756 in the precise location of Blancpain's trading post. Lieutenant Domingo del Rio was appointed commander of the presidio. The Spanish then established the accompanying Mission of Nuestra Señora de la Luz del Orcoquisac for the Akokisa. Calling the site El Orcoquisac, they made plans to turn it into a civil settlement of 50 families, creating a permanent Spanish presence in the Galveston Bay area.

The presence of the presidio hampered local trade between the French and local Indians, but the Spanish were not able to form their own trading relationships with these groups. The Spanish mission-presidio complexes were not designed to be entrepreneurial in nature and did not stock the kind of provisions necessary to maintain ongoing trading partnerships. In addition, they often suffered from shortages of basic supplies, leaving little leftover for trade. As a result, the Spanish could only act as middlemen, exchanging goods between the French and Indians.

In 1758, the idea of turning El Orcoquisac into a civil settlement was abandoned, due to lack of funds and interested settlers. The mission was moved 1 kilometer east of the presidio the following year. In 1763, Captain Rafael Martínez Pacheco replaced del Rio as commander of the presidio in response to complaints from the officers of dwindling supplies of food, clothes, and ammunition. By this time, the mission had fallen into a dilapidated state. Pacheco attempted to rebuild it and revive interest in mission life among the Akokisa by supplying a herd of beef cattle and tools for agriculture. Official support for the project was slow in coming, however, and Pacheco was regarded as cruel and arrogant by the soldiers, who deserted the presidio in 1764. Ruiz was sent to relieve Pacheco of his duties, but Pacheco and a handful of supporters refused to surrender the presidio. After a five-day standoff, Ruiz set fire to Pacheco's quarters in an effort to drive him out. The fire soon spread to the barracks and presidio church, greatly damaging both, while Pacheco escaped through a secret passage in his quarters. Ruiz then took charge of the presidio until he was arrested in 1765 for the crime of having set the presidio on fire. Melchor Afán de Rivera replaced him as commander.

In 1766, a hurricane severely damaged the presidio and completely destroyed the mission. The mission was rebuilt in the same location and the presidio was rebuilt 1 kilometer east, close to the mission. The following year, the Marqués de Rubí made a formal inspection of the presidio and concluded that it was of little strategic importance to Spain. The mission had also proved to be a disappointment, as only 30 Akokisa had been baptized. In 1769, Pacheco was cleared of any responsibility in the burning of the presidio and his position as commander was restored. His tenure was short lived, however, as El Orcoquisac was abandoned in 1771. During the next few years, the Akokisa used the buildings as a meeting place to trade with the Atakapa and Karankawa, before they too abandoned it.

Archeological Investigations

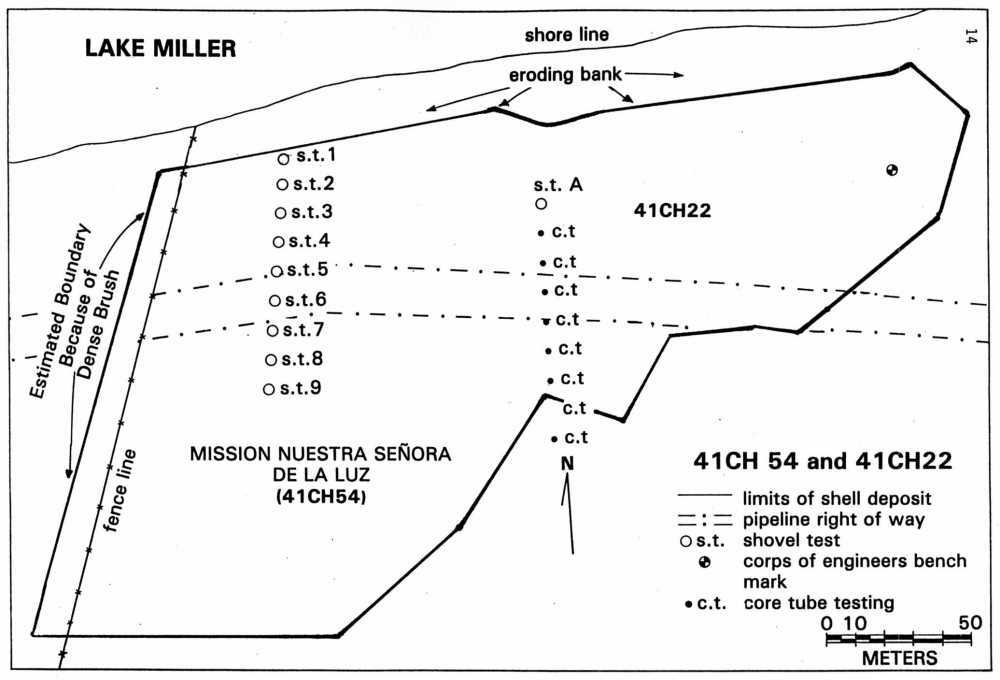

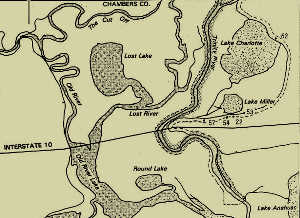

The second location of El Orcoquisac was discovered in 1966 by amateur historian John V. Clay with the aid of Spanish colonial documents and maps. Clay contacted Curtis Tunnell, State Archeologist, and J. Richard Ambler, Director of the Texas Archeological Salvage Project, who performed surface collections and shovel tests at the site and confirmed that it was the post-hurricane location of the presidio (designated 41CH53) and mission (designated 41CH54).

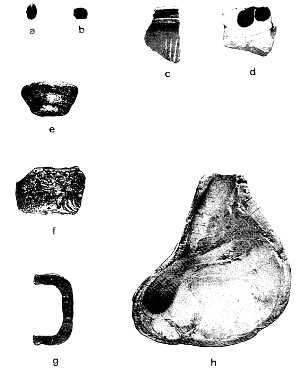

Soon afterwards, Tunnel, Ambler, Clay, and William L. Fullen embarked on a project to identify other historical sites in the surrounding area. They performed surface collection and test excavation at a large Rangia shell midden reported by archeologist Harry J. Shafer in 1966 (41CH22), and recovered 161 bone fragments, 88 prehistoric ceramic sherds, 10 chert flakes, and 1 blue glass bead. Of the bone fragments that were identifiable, 1 belonged to white-tailed deer, 1 to turtle, and the rest to fish, namely alligator gar, other gar, catfish, and striped mullet. The ceramics were identified as grog-tempered and sandy paste untempered wares. Based on the ceramics and the glass bead, occupation of the site may have begun as early as A.D. 1000 and continued to the time of Spanish contact. Based on the location of the site, it may represent the Akokisa encampment used when the presidio and mission were in operation, though none of the artifacts recovered from the site can confirm this.

By studying Spanish colonial documents and surveying the surrounding area, Tunnel, Ambler, Clay, and Fullen were also able to find the first location of El Orcoquisac (41CH57), believed to overlie Blancpain's trading post. In 1970, Fullen directed a project of the Houston Archeological Society to evaluate the archeological potential of the site. Aerial color infrared photographs were taken and topographic mapping, metal locator survey, surface collection, soil coring, and test excavations were carried out.

The trading post, and subsequently the presidio and mission, were built on a prehistoric Rangia shell midden. The project recovered 371 bone fragments, 2 flakes, 78 unidentifiable prehistoric ceramic sherds, 2 sherds of blue-on-white majolica, 4 fragments of a green bottle, and part of a metal buckle. The faunal remains consist almost entirely of fish, namely alligator gar, other gar, sheepshead (a type of drum), and either black drum or spotted weakfish. The rest of the remains belonged to white-tailed deer, cow, and turtle. The prehistoric ceramics were identified as grog-tempered and sandy paste untempered wares.

In 1979, the Center for Archaeological Research at the University of Texas at San Antonio conducted further studies, as part of the larger Wallisville Lake project, that shed light on the role of El Orcoquisac during the Spanish Colonial period. The CAR archeologists led by Anne Fox, Lynn Highley, and William Day, delved deeper into the historical accounts and evidence from the Spanish Colonial sites. They concluded that both the mission and presidio failed for a combination of reasons: poor environmental conditions, poor planning and lack of volunteer settlers, poor leadership, and power struggles to control trading/smuggling operations on the frontier at that time. In the end, as they noted, neither the Indians nor the Spanish could sustain an uneconomical and degenerating settlement. The lack of converts made it impossible for the church to sustain a missionary operation.

The El Orcoquisac Archeological District is a significant cultural resource of the French/Spanish Colonial period in southeast Texas. In the future, area residents hope to create a historic park with interpretive displays focused on the short-lived French trading post and Spanish settlement.

Contributed by Carly Whelan, based on the sources below.

Sources

Fox, Anne, D. William Day, and Lynn Highley

1980 Archaeological and Historical Investigations at Wallisville Lake, Chambers and Liberty Counties, Texas. Center for Archaeological Research, The University of Texas at San Antonio, Archaeological Survey Report 90.

Fullen, William Louis

1978 El Orcoquisac Archeological District, Wallisville Reservoir, Texas: Past, Present, and Future. Journal of the Houston Archeological Society 59:5-12.

Highley, Lynn, Anne Fox, and Will Day

1982 Mission Nuestra Señora de la Luz and Presidio San Augustín de Ahumada: The Orcoquisac Historic District in Chambers County, Texas. La Tierra 9(2):2-17.

Download article![]()

Ricklis, Robert A.

1994 Aboriginal Life and Culture on the Upper Texas Coast: Archaeology at the Mitchell Ridge Site, 41GV66, Galveston Island. Coastal Archaeological Research, Inc., Corpus Christi, Texas.

Tunnell, Curtis D. and J. Richard Ambler

1967 Archeological Excavations at Presidio San Agustín de Ahumada. State Building Commission, Austin.

Links

|

|

|

|

|