Shell Mounds and Shellfish: Staff of Prehistoric Life?

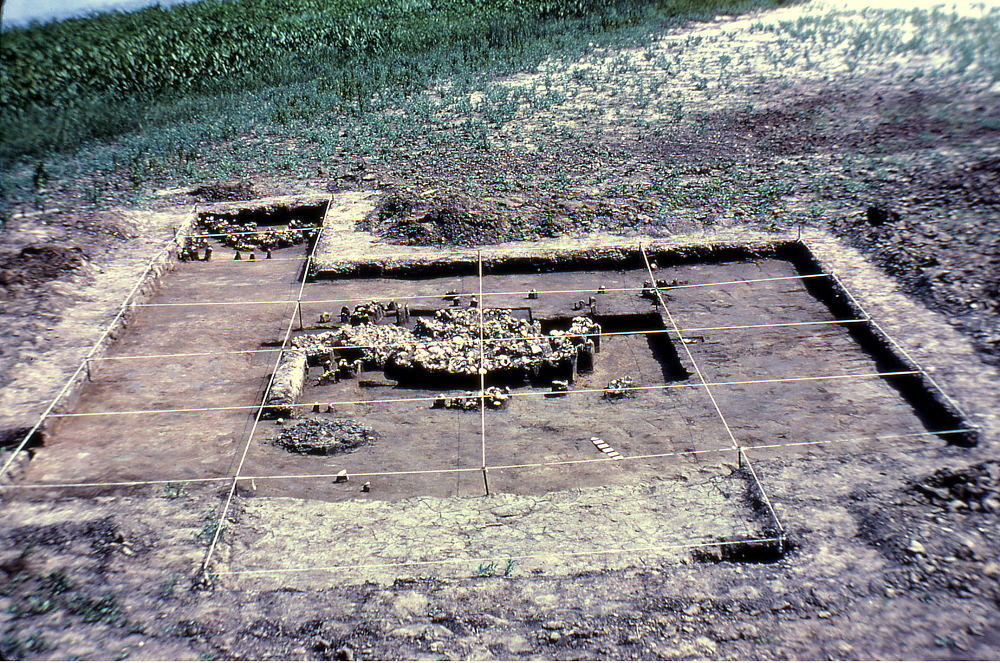

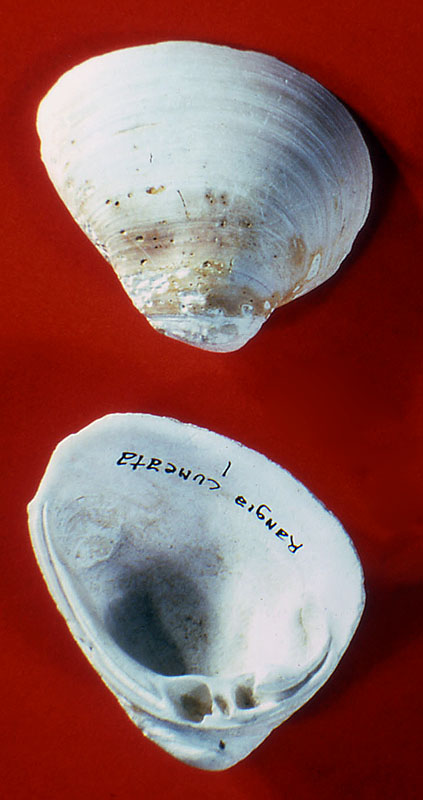

The physical bulk of prehistoric archeological sites of the Texas coast typically is comprised of some proportion of a dozen or so species of shellfish. In habitats from fresh water to the marine waters of the Gulf it is not unusual to encounter freshwater bivalves, Rangia cuneata (common rangia), Crassostrea virginica (Eastern oyster), and various other estuarine bivalves, sometimes in dense concentrations. Estuarine gastropods and surf clams of several species are also found and while they probably contributed to the native diet, apparently these were mostly collected for use as tool and ornament materials.

Over all, the clam Rangia cuneata was the shellfish of the greatest subsistence importance to prehistoric peoples, and is of the greatest analytical importance to archeological investigations along the coast of the northern Gulf of Mexico. This low-salinity pelecypod probably accounts for 80 percent or more of all mollusc shells found in archeological sites located around the estuaries and coastal marshes especially on the upper coast. The natural abundance of Rangia cuneata in this region is staggering. A modern survey of just that part of coastal Louisiana between the Atchafalaya and the Calcasieu rivers estimated the standing crop of Rangia there at around 30 to 50 billion clams, an order of magnitude that may have been available to prehistoric food gatherers as well.

Next in importance among other bivalve molluscs in this region, the Eastern oyster (Crassostrea virginica) is a minor constituent of many archeological sites and a major constituent primarily toward the central Texas coastal region. All other species of freshwater, estuarine, and nearshore marine molluscs are rare in their archeological occurrence, with occasional exceptions. Most of these several kinds of shellfish usually can be found anywhere on the Texas coast from Sabine Lake south to the Rio Grande delta, although in radically different proportions. Rangia cuneata is the dominant resource in the upper coast but the greatest diversity of species occurs as one moves down the coast into warmer waters. Along the central coast rangia are also more common except at bay shoreline sites where oysters are often the dominant resource, and a dozen or so other species are occasionally found in prehistoric sites. The shellfish exploitation patterns in the Rio Grande delta area are poorly known, but surface collections show that a greater array of shellfish species were used to make shell ornaments and tools that elsewhere along the Texas coast.

So, overall the Rangia cuneata clam appears to be the principal food shellfish comprising shell mounds on the Texas coast with the Crassostrea virginica oyster a distant second. This is not necessarily how it was when shell mounds were in formation. If we take Galveston Bay or Baffin Bay as an example, it is certain that a significant amount of peripheral erosion has occurred especially in the last century – erosion that took with it many archeological shell sites which undoubtedly were principally comprised of oyster shells since the bay shore was adjacent to prime oyster habitat. In historic times the accessible bay edges near populated areas all along the coast were effectively mined for shell for use as road base and construction fill. Many shell mounds left by native peoples, especially the larger accumulations of oysters, would have been selectively targeted and removed beginning in the late 19th century.

Molluscs in general are highly informative in modern archeological research. This includes high-resolution absolute dating, estimating ancient water salinity and temperature, determining dietary contributions, differentiating deposits and identifying features in archeological sites, recording effects of human predation on shellfish populations, analyzing the paleoecological setting of the site, and for other applications. It may be said that the archeological utility of molluscan remains is limited only by the imagination of the investigator.

The presence of a host of different species in Texas coastal archeological sites, as described above, is a matter of record but their archeological significance is not always understood. As examples, let us focus on two very different analytical values that shellfish have – for human nutrition, and for determining what the coastal landscape was like at the time a particular shell mound was being formed.

Nutrition: It is generally assumed that the shells in a shell site are the residues from aboriginal meal times. But some investigators question this assumption usually on grounds that the nutritional value (say, calories and protein) of the Rangia clam and the Crassostrea oyster are less than half that of an equivalent amount of venison from the white-tailed deer whose bones are often found in shell sites too. So what is the attraction of shellfish as a food item? Are shellfish a steady part of the diet or might they instead be a crisis food – something eaten when there are extreme shortages of the usual dietary plants and animals as during a period of drought. And still others have seen shell sites more as structures than as food. That is they were heaped up to create a permeable platform usable for habitation in the marshes during wet seasons. In fact, available studies seem clear that shellfish primarily was a category of food. Yet their role in the coastal food economy relative to other resources, and in other activities, is not yet completely clear.

Landscape interpretation: Sea level has been rising for some 15 to 18 thousand years and as it does so it displaces toward the land the Texas coastline and its component parts. While doing this it continually submerges older coastal sites with the result that today it is not known when the earliest coastal archeological sites were formed. We have many sites of Middle Archaic age (circa 4500 years ago) with some on the central coast estuaries that may be 7500 years old (circa Early Archaic or late Paleo-Indian). Some submerged shell piles off Sabine Pass on the order of 8000 years old also are suspected of being archeological sites.

The geography of the Texas coast is highly structured around major streams draining freshwater into estuaries or lakes, and from there into the coastal lagoons or the open Gulf. In some places the rivers have filled their estuary and flow directly into the Gulf (for example the Brazos and the Rio Grande). This structure yields a distinct salinity gradient from inland freshwater, to high salinity of the open Gulf.

The ecology of most Texas shellfish has been studied and the shellfish species or combinations of species (and their characteristic salinity and substrate preferences) as found in archeological sites allow interpretations to be made of the likely place in the river-delta-estuary-lagoon-Gulf continuum where the shellfish were collected. This, along with other lines of evidence, often permits an interpretation to be made of the endlessly changing coastal geography over the past 18 thousand years of rising sea level and the native peoples’ use of the coast.

In conclusion, it is fair to say that shellfish are one of the most complex components of coastal archeological sites. Generally they were a reliable food except in the margins of their preferred salinity, substrate, or other habitat conditions such as air temperature. For example, Rangia cuneata are very hard to find in shallow waters during the winter cold and so winter use of that species is unlikely. At a much larger scale, consider Baffin Bay, a once suitable estuarine habitat where oysters thrived, that turned hypersaline as it is today and became unsuitable for most shellfish.

But, even if more or less reliable to collect and clearly consumed in significant quantities, we have to ask what were the implications of the nutritional deficits of shellfish? This is a question currently without an answer, a situation even further complicated by the erosional removal of bay shore (and sites) on the upper and lower coasts, and to some degree the central coast. Add to the natural destruction the purpose removal of shell for construction and it is understandably that the role of bay species in prehistoric diet and activities can no longer be easily assessed, if at all. Beyond an undefined place in the prehistoric diet and material for a dry platform on which to camp, shellfish also provided native peoples with a variety of tool and ornament materials both for their direct use and probably for trade to inland peoples.

Finally, shellfish in their archeological context provide investigators an invaluable archeological tool for many purposes – radiocarbon dating, environmental reconstruction, analyzing site structure, analyzing impact of human (native) predation on shellfish populations, enhancing preservation of bone in sites, and more.

Contributed by Lawrence E. Aten.

Sources:

Aten, Lawrence E.

1983 Analysis of Discrete Habitation Units in the Trinity River Delta, Upper Texas Coast. Texas Archeological Research Laboratory, Occasional Papers 2.

Steele, D. Gentry

1987 Utilization of Marine Mollusks by Inhabitants of the Texas Coast. Bulletin of the Texas Archeological Society 58: 215-248.

|

|

|