Buffalo Gourd

Cucurbita foetidissima H.B.K.

Cucurbitaceae (Squash Family)

Buffalo gourd is a perennial that grows from a large tuberous root. It produces very long stems that trail along the ground for several yards, along which small, round gourds form. The roots, stems, and leaves were used for a variety of medicinal needs and the seeds were eaten.

The large, roughly triangular leaves of this plant are coarse, almost leathery, and emit what many consider an offensive odor when brushed against. The flower has five yellow petals and measures up to four inches from the base, and the fruit, which is green with white stripes but ripens to a yellowish green, is a globe-shaped gourd measuring 3-4 inches in diameter. The root can measure over one foot in diameter, and is described as spindle-shaped in some sources, thickest in the middle and tapering at each tip (Correll and Johnston 1970). The form of the root, however, is quite variable. Some buffalo gourd roots are over 15 inches wide at ground surface, and then split into two "legs" extending three feet deep, resembling a human form. Buffalo gourd is widespread in open disturbed areas in the Amistad Reservoir area.

Archeological occurrence. Seeds of buffalo gourd have been recorded from deposits in Hinds Cave near the lower reaches of the Pecos River. The roots were recovered from Tularosa Cave in New Mexico (Cutler and Whitaker 1961). The finds from Tularosa were recovered before the widespread use of radiocarbon dates, but the Hinds Cave material comes from deposits dated to the Middle Archaic period about 5,000 years ago and Late Archaic period about 1200 years ago (Dering 1979; 1999).

Ethnographic accounts. Both the root and the fruit/seed of the buffalo gourd were utilized by indigenous North Americans. They valued the root for its medicinal properties, and the seeds as a food source. The fruit and roots contain cucurbitacins, a group of triterpenoid glycosides that imparts a very bitter taste, and that can be poisonous in high concentrations. Cucurbitacins are produced by all members of the squash family, but they have been greatly reduced in domesticated squashes and cucumbers. The buffalo gourd, however, is rich in cucurbitacin and consumption of this plant requires some processing. Although there are accounts of other parts being consumed, most references mention only the seeds as a food source. The shell of the gourd, the leaves and stems, and the root had other applications.

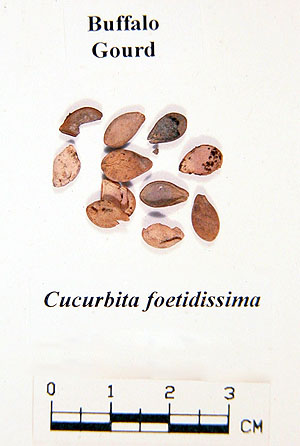

Healing and ritual. Some Plains Indians believed the buffalo gourd to be a powerful plant. The large root, quite variable in form, was considered by the Dakota and the Omaha-Ponca to have special healing powers. They used the root according to the doctrine of signatures, which meant that the specific application of each root was defined by its shape and resemblance to the human body. Some buffalo gourd roots were ascribed to the female human form and others to the male human form. For example, the root in the accompanying photograph is reminiscent of the female form. Healing was effected by removing the area of the root corresponding to the patient's body and placing it on the afflicted body part (Gilmore 1919:65).

The root has other medical applications which are related here strictly for historical purposes. The chemical contents of the buffalo gourd are quite potent, including saponins and cucurbitacins, which means that they are potentially poisonous if misapplied. None of the brief discussions in this vignette carry details known to the elders who actually used these plants for healing. This author's experiences with earth oven cooking and other plant processing endeavors have taught him that most ethnobotanies, in fact, are lacking in the details that insure culinary success. Therefore any healing applications, which in fact utilize the very chemicals that food preparations remove from plants, should be only be attempted with the tutelage of an experienced herbalist or healer.

The Isleta pounded and boiled the root, using the resulting topical infusion to relieve chest pains. A powdered extract of the root is a powerful laxative, perhaps a little too powerful, for it is said to induce cathartic symptoms (Dunmire and Tierney 1995; Robbins et al. 1916). Obviously this is not a remedy one would want to use while traveling on a bus or an airplane.

In topical applications the root also has astringent or disinfectant properties. Both the Western Apache and the Pueblos utilized a poultice of the roots, which was applied as a cleansing agent to sores or boils (Curtin et al. 1997). The Cahuilla also pounded the root and applied it directly to sores (Bean and Saubel 1972).

Other uses. The roots are also rich in saponins, a chemical combination of steroids and sugars that foam when water is added to the sap and agitated (Nobel 1994). Both the root and the outer shell of the fruit are sufficiently rich in saponins that they were used for hand and laundry soap as well as shampoo (Bean and Saubel 1972: 58).

Buskirk (1986:192) notes that the Western Apache mashed the stem, leaves and root, mixed them in hot water, and used the resulting mass like a veterinary dip for treating saddle sores on horses. This use provides compelling evidence for the potency of the buffalo gourd root and stems, and perhaps a cautionary not to not try this poultice on a human.

Food and nutrition. The seeds are edible and several Native American groups used them for food. Because of the widespread use of the seeds and the size of the taproot buffalo gourd was thought to be a potential dry-lands food source, hence, it was the subject of nutritional research. The seeds contain between 25-42% fat (Berry et al. 1976). Fat in the form of vegetable oil would be a critical dietary component in a desert, where animals carry very little fat on their bodies. Buffalo gourd seeds are also high in protein (22-35%) making them comparable to some legume seeds.

The seeds were roasted or boiled, and either eaten or ground into a meal. The Gila River Pimas of Arizona parched the seeds and ate them (Russell 1908:70). Other groups, such as the Luiseno and the Cahuilla of southern California, ground the seeds, mixing the resulting flour with water into a mush or paste (Bean and Saubel 1972:57; Sparkman 1908:229).

References:

Bean, Lowell J. and Katherine S. Saubel

1972 Temalpakh: Cahuilla Indian Knowledge and Usage of Plants. Malki Museum Press, Morongo Indian Reservation, Banning, California.

Berry, J., C. Weber, M. Dreher, and William E. Bemis

1976 Chemical Composition of Buffalo Gourd, A Potential Food Source. Journal of Food Science 41: 465-466.

Buskirk, Winfred

1986 The Western Apache: Living with the Land Before 1950. University of Oklahoma Press, Norman, Oklahoma.

Correll, Donovan S. and Marshall C. Johnston

1970 Manual of the Vascular Plants of Texas. Contributions from the Texas Research Foundation, Volume 6, Renner, Texas.

Curtin, Leonora Scott Muse, Michael Moore, Mimi Kamp, and Mary Austin

1997 Healing Herbs of the Upper Rio Grande: Traditional Medicine of the Southwest, Western Edge Press, Santa Fe, New Mexico.

Cutler, Hugh C. and Thomas W. Whitaker

1961 History and Distribution of the Cultivated Cucurbits in the Americas. American Antiquity 26(4):469-485.

Dering, J. Philip

1979 Pollen and Plant Macrofossil Vegetation Record Recovered from Hinds Cave, Val Verde County, Texas. M.S. thesis, Texas A&M University. Published by the Department of Anthropology. College Station, Texas.

1999 Earth-oven Plant Processing in Archaic Period Economies: An Example from a Semi-Arid Savannah in South-Central North America. American Antiquity 64(4):659-674.

Dunmire, William W. and Gail D. Tierney

1995 Wild Plants of the Pueblo Province, Museum of New Mexico Press, Santa Fe, New Mexico.

Gilmore, Melvin R.

1919 Uses of Plants by the Indians of the Missouri River Region, University of Nebraska Press, Lincoln. [1977 reprint of original, Thirty-third Annual Report of the Bureau of American Ethnology, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, D.C.]

Nobel, Park S.

1994 Remarkable Agaves and Cacti. Oxford University Press, Oxford. UK.

Robbins, William W., John P. Harrington, and Barbara Freire-Marreco

1916 Ethnobotany of the Tewa Indians. Bureau of American Ethnology Bulletin 55, p. 63, Smithsonian Institution, Washington D.C.

Russell, Frank

1908 The Pima Indians. Twenty-sixth Annual Report of the Bureau of American Ethnology. [1904-1905], pp. 17-389, Washington, D.C.

Sparkman, Philip S.

1908 The Culture of the Luiseño Indians. University of California Publications in American Archaeology and Ethnology 8(4):187-234.

![]()