Introducing Lower Pecos Rock Art

Native peoples—Indians or Native Americans—came into what is now Texas by at least 13,500 years ago and never left. The 13,000-year prehistoric legacy they left behind represents over 500 human generations, but most of this legacy is recorded in bits and pieces of broken things, layers of dirt, and scattered campsites. Easy enough to find, but hard to decipher. In contrast, the vivid art native peoples left behind on protected rock walls are haunting and evocative reminders of their presence. These pictographs and petroglyphs help us understand how native peoples viewed their physical and supernatural worlds.

Though Indian peoples left their marks on the walls of hundreds of sites in the western half of Texas, the largest and most distinctive collection of rock art comes from the Lower Pecos Canyonlands, where the Pecos and the Devils Rivers flow into the Rio Grande. For a more comprehensive introduction to the area, check out the extensive Lower Pecos exhibit elsewhere on this website.

Hunting and gathering societies inhabited the Lower Pecos area for 13,000 years, finding everything they needed for survival within the canyons and across the sheltering uplands. They often visited and stayed in the many natural rockshelters (overhangs) and shallow caves found within the canyons. Because of the arid climate (today the area gets an average of only 14-18” of rain per year), the dry rockshelters preserve evidence of everyday life as well as their art.The evocative images left behind by Lower Pecos peoples provide us with a connection to their lives and experiences.

Cross cultural studies have shown that the world’s hunting and gathering peoples often believe that everything has a "cosmic soul" or is alive. Animals and people are equal. Plants and stones are also thought to have spirits. The peoples of the Lower Pecos may have believed that nothing could be taken without some kind of payment; relationships were reciprocal.

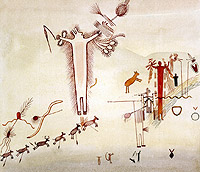

They practiced shamanism, a type of “primitive” religion shared by most hunting and gathering peoples the world over. Shamans were individuals with a special calling who acted as spiritual leaders, doctors, historians, scientists, and teachers for their people. They functioned as go betweens for the people and the spirit world. By entering trance-like states of conscious, shamans were thought to be able to transform themselves temporarily into part human and part animal beings. To visit the other world they became flying birds, swimming fish, or prowling cats.

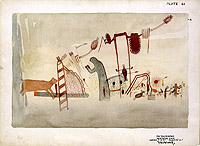

Shamans and shamanistic scenes dominate the pictographs and murals painted on the protected rock walls of the Lower Pecos. Intricate, colorful paintings depict the shaman's trip and the physical and supernatural worlds.

Research on these paintings offers fertile ground for archeologists and ethnologists as can be seen in the work of contemporary researchers. Of those active today, Carolyn Boyd and Solveig Turpin are the leading interpreters of Lower Pecos rock art and both have written books and articles explaining their views.

Here are some basic facts about Lower Pecos rock art.

- The art of the Lower Pecos Canyonlands consists of:

- Pictographs- drawings or paintings on rock.

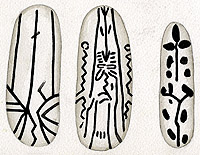

- Painted Pebbles- portable art painted on smooth oval pebbles.

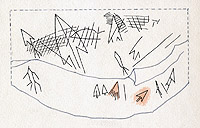

- Petroglyphs- carvings or inscriptions on rock.

- The paints were made of natural minerals such as iron oxide (hematite) that was ground into a red paint pigment with stone wooden tools. To liquefy the pigment, binders like animal fat and emulsifiers such as soapy yucca root sap were added.

- The colors were shades of red, black, yellow, orange, and white.

- The leaves of desert plants like sotol and lechuguilla provided fiber for brushes. Sometimes crayons were also used. These were molded from dry pigment. (One 14-inch yellow crayon was found.) Sometimes finger painting and spattering were used.

- River claim shells and thin stone tablets served as palettes.

- The artists, probably shamans, created some incredibly large pictographs that could only have been done by using special equipment. At Panther Cave, one panther is nine feet across and the top of a shaman figure is 12 feet above the shelter floor. Some murals are 30 feet wide. These heights indicate that the artists used wooden ladders and scaffolds.