Silo Site

In the gently rolling landscape of central Karnes County, the Silo site (41KA102) sits atop a low ridge overlooking a small, unnamed, wet-weather creek that flows into the San Antonio River to the south. Mesquite trees, hackberry, prickly pear cacti, and brush grow dense along this creek and its surroundings. Cattle meander through, grazing on the patches of thin grass. Native peoples used the site for a camping spot at various times during the Archaic era. In the Late Archaic period, roughly 2000 years ago, people began to use the site as a cemetery.

In the 1950s, a deep silage trench some 180 feet long, 20 feet wide, and 10 feet deep was dug down the length of the ridge, cutting straight through the Silo site. At the time, some ranchers used such trenches to store green fodder for livestock feed, a practice now used rarely because of improved storage methods. Some abandoned silage trenches were backfilled, but in this case the trench was left open and the walls slowly eroded.

In 1995, some forty years after the trench’s excavation, the landowner noticed what he surmised were human bones eroding out of the south wall of this trench. He contacted Dr. Thomas R. Hester at the University of Texas at Austin, who soon came down to take a look. Hester and several of his students found the remains of several human burials eroding out of the south wall of the silage trench. Fire-cracked cooking stones, stone tool-making debris, animal bone fragments, freshwater mussel shells, and occasional stone tools, all evidence of intense prehistoric activity, were scattered across the surface of the ridge. The trench wall revealed a thick upper layer about a meter thick (39 inches) within which were numerous artifacts similar to those found on the surface as well as human remains.

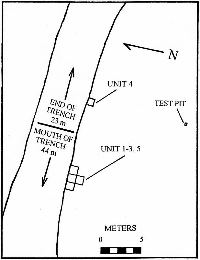

It was obvious that the steep trench wall would continue to erode and destroy what remained of the burials. Small-scale salvage excavations were undertaken the following year by student volunteers under the direction of Troy Lovata, then a graduate student at UT-Austin. Salvage work continued intermittently for about two years. Skeletal remains representing about 25 individuals were encountered in five 1-x-1-meter excavation units placed along the silage trench wall. Additional research by Cory Broehm and several other volunteers recovered one more burial and helped to define the site more clearly.

The prehistory of the site, aside from the burials themselves, is largely a mystery. The occupation zone had been heavily disturbed by humans in ancient and modern times as well as by the forces of nature, especially rodent burrowing and tree roots, obscuring much of the site’s developmental history. People occasionally passed through this location as early as the Paleoindian period and again in Early Archaic, and possibly, Middle Archaic times. The only definitive evidence they seem to have left behind is a Paleoindian point base and, during the Early Archaic, an Early Triangular dart point and several Clear Fork and Guadalupe adzes. All of these artifacts, except one Guadalupe tool (see photograph), were found on the surface of the ridge, but the limited testing suggested that whatever evidence of their activities might exist, it is likely mixed in with that from later occupations.

About 2000 years ago, peoples began to visit the Silo site more frequently and stayed longer as well. Numerous fire-cracked rocks show the ridge was used for cooking and perhaps heat-treating chert (flint) for stone tool manufacture. Some of the cooking activities could be related to rituals related to the cemetery, such as feasting. But most of the occupational debris likely stems from ordinary camp activities. Flakes and bifacial tools were made and sharpened to hunt game with darts tipped with Ensor, Fairland, and Matamoros projectile points. Mussel shells, and, no doubt, fish and other riverine species such as turtle, were pulled from the nearby stream or, more likely, from the San Antonio River itself. Although no direct evidence was found, we can be sure that Late Archaic visitors were also gathering plant foods as well, such as pecans and prickly pear. The site setting within the San Antonio River valley provided ready access to habitats ranging from the river itself to dense riparian woodlands and nearby upland areas.

At some point during the Late Archaic period, the group (or groups) who frequented the site began to think differently about the ridge and its place in the life of the group and the landscape. Instead of just being a convenient camping place, a portion of the Silo site became designated as a place to bury their dead – a cemetery. Burials have also been found at two other Late Archaic sites nearby in Karnes County, including the Rudy Haiduk site (41KA23). Neither of these sites has been investigated well and it is not certain whether these are also cemeteries or just places where isolated burials occur.

The span of time during which the Silo ridge was used as a cemetery is unknown; no radiocarbon dating has been done. But as the number of burials grew, rather than expand the size of the cemetery across the ridge, which held ample room for more burials, people chose to continue burying in the same small area where they had begun. As they returned to the same small spot on the ridge over and over again, they dug through the graves of those laid down before, to make new graves for the recently dead.

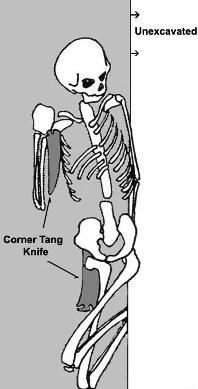

The archeologists found striking evidence of the reuse of the cemetery. The first bones encountered, as little as 20 cm (8 inches) below surface, were usually dissociated pieces of bone, or bones in jumbled masses. It was also not uncommon to find, for example, an isolated skull, a headless body, or an articulated arm or ribs and vertebrae with no other associated remains. The picture that emerged as each piece of bone was mapped and cataloged was that this small plot was used and reused for multiple interments, later burials cutting through earlier ones, often leaving part of the disturbed body intact and articulated. Graves were then backfilled with the jumbled elements of those graves they had disturbed in their digging. Burials were as shallow as 30 cm below the ground surface, but most were 70 to 90 cm deep. Only six burials, invariably the deepest, were found whole and undisturbed. These are thought to represent the latest burial episodes at the site, and bodies which had been laid to rest in grave pits dug through earlier burials, causing additional mixing.

The Silo “burial population,” or excavated sample, consists of about 25 individuals, many of whom were represented only by a few bones. Careful study of human bones can sometimes tell us a great deal about ancient life. There are several factors, however, that limit what can be learned from the Silo population. To begin with, only a very limited area of the site was excavated. An unknown number of graves were destroyed by the excavation of the silage trench and subsequent erosion. Based on the surviving traces, we suspect that many more graves were originally present. The often incomplete skeletons further hinder what can be learned.

Nonetheless, based on the recovered sample of the remains of a minimum of 25 individuals, the Silo site is remarkable for the large proportion of children buried there. Analysis suggests that twelve of the recovered individuals were less than 20 years old at death and thirteen were older than 20 years. Nine were less than ten years old. Whether this is a chance occurrence that the area of the cemetery with the most children survived while more adults were destroyed by the silage trench is unknown. Surely it is not a preservation bias, as the bones of younger persons are more fragile and less likely to survive than those of adults. Nonetheless, the ratio of children to adults is intriguing. Two of the three individuals at Silo who were buried with grave offerings are children, suggesting perhaps that the children in this society had a relatively high status.

Of the thirteen adults, seven are males and one is female. The gender of the others could not be determined. With a couple of exceptions, no real assessments of the ages of the adults could be made due to the fragmented and weathered condition of the bones.

Few health problems were identified, although bone is usually one of the last tissues to show any sign of disease or ill health, and the absence of any of these signs in bone may simply mean the individual died before the skeleton was affected. Two children exhibit some evidence of an infection in or around the ear, but this may or may not have been the cause of death. One adult male shows evidence of a healed fracture of the tibia (shin bone). The teeth of these people are usually heavily worn, as is common with native groups with a gritty diet high in raw foods. This wear, however, seems to buffer against the formation of cavities, which were largely absent in the Silo population, although very common among prehistoric remains from the Southern Edwards Plateau and the Lower Pecos Canyonlands. This suggests the diet of those buried at the Silo site was not based on the carbohydrate-rich (sugary) plants known to promote cavities.

Worldwide, cemeteries are places that are considered sacred by those who bury their dead there. The act of burying a loved one is almost always accompanied by ritual such as special ceremonies and sometimes by special offerings, many of which may have been made of perishable organic materials such as leather, wood, and fiber. Much of the ritual and custom attending the burial of a person leaves little to no evidence in the archeological record, or may not be recognizable.

For example, most of the occupational debris at the Silo site is interpreted as evidence that the site was also an ordinary campsite. Yet, we cannot rule out the possibility that funerary rituals such as feasting in honor of the deceased may have contributed to the debris accumulation. It could also be the case that much of the camping debris may have accumulated when people gathered to bury one of their own, rather than during ordinary camping episodes. Interestingly, artifacts (both on and below the surface) are most numerous on top of, and immediately around, the graves, and fall off considerably in density across the rest of the ridge.

Nonperishable information available to the archeologist, such as the position of the body and its orientation, unusual or rare treatment such as cremation, and the inclusion of highly valued objects in the grave are steeped in tradition and meaning, but these are hidden as well. Comparisons of practices between or within cemeteries, or changes through time, provide one analytical tactic that can be employed to attempt to track the change in meaning and tradition, if not its substance.

All the burials at the Silo site were single interments, with one exception. One double burial was recorded, that of a young man who was buried with a 5 to 6 year old child. The dead were placed in the grave in a variety of positions. Many were semi-flexed (knees tucked in toward the chest) and lying toward one side or facing up. Several had the legs flexed under the body, the arms bent, and one hand placed on the pelvis the other on the face. These are common burial positions among Late Archaic populations in southern Texas. Only a single individual, a woman, was placed face down in an extended prone position. The cultural beliefs and practices of the group apparently dictated this woman required unusual treatment when she died. The reason for such a burial is unknown, but a similar burial has been reported from the Ernest Witte site in Austin County in southeast Texas.

Another unusual pattern at the Silo site is that one person, possibly two, had a small stone placed in the mouth when they were buried. This practice has so far only been documented at the Oso Dune site in Corpus Christi, although this is the kind of practice that is easy for archeologists to miss when excavating (who might reasonably assume that the rocks were simply from the surrounding soil).

Grave offerings are fairly common at many cemeteries, but few were found at the Silo site. While few, they are dramatic. With the child of the double burial were three large corner-tang bifaces (knives) and three large biface “blanks,” (thin bifaces thought to represent unfinished tools) all made of Edwards chert from the eastern Edwards Plateau. These pristine artifacts suggest that the child was held in very high esteem. Two similar large corner-tang knives (also of Edwards chert) accompanied another adult male burial. The combination of quality, size, and context of these artifacts, is exceptionally rare. Corner-tang knives as grave furnishings are known from the Ernest Witte site and the Rudy Haiduk site. Similar specimens from the Morhiss Mound site along the Guadalupe River in Victoria County, and at the Bowser site in Fort Bend County in southeast Texas may also have originally been with burials.

Microscopic examination of the Silo bifaces revealed they had never been used, and indeed the corner-tangs were probably never intended to be used. The corner tang or notched rounded projection was used to hold the binding (probably sinew) to attach the knife to a wooden handle. The large size of the Silo knife blades, relative to their tang and base was so great that actual use of the tool as a knife likely would have resulted in the tool breaking. The fine form strongly suggests that the Silo Corner Tangs were intended for a ritual purpose such as accompanying the dead, and were seen as symbols of status, authority, or individual honor.

Few other grave offerings were found at the site, but this may be in part due to disturbed nature of many of the burials (and of the cemetery itself). The only other artifact definitely placed in a grave was a marine shell pendant found with a child. These are a relatively common grave good and may be the only surviving part of a garment, or purely decorative. Two deer-antler billets (flintknapping tools) were likely grave inclusions as well, but they were found within disturbed areas of the cemetery and their association with burials is uncertain.

The corner-tangs and bifacial blanks, as well as the marine shell pendant, also suggest the peoples at the Silo site traded with groups on the Edwards Plateau and as well as along the coast. Such trade or exchange networks have been well-documented during the Late Archaic at other sites throughout central, southern, and, especially, inland southeast Texas. At the Ernest Witte site, for example, there are exotic burial goods made of materials that can be traced to the Midwest and Southeast, hundreds of miles distant. The trade in evidence at the Silo site was apparently more modest, but nonetheless crucial for the exchange of idea, news, and goods, as well as the development of relationships between groups and individuals.

In summary, the Silo cemetery provides a glimpse into the lives of Late Archaic hunting and gathering peoples whose territory included the drainage basin of the San Antonio River in the South Texas Plains. Around 2000 to 1500 years ago, closely related peoples (perhaps a single group) established a small cemetery on a ridge overlooking the San Antonio River valley. They returned there many times to bury their dead, especially their children, and often dug new graves which disturbed and displaced earlier graves. This pattern suggests that the cemetery was used for several generations and that enough time elapsed between burials that the exact grave locations were no longer known.

Contributed by Cory Julian Broehm.

Sources

See Loma Sandia, Morhiss Mound, Olmos Dam, and Buckeye Knoll for related cemetery discussions and Mortuary Traditions for an overview.

Broehm, Cory J.

2001 Hunter-Gatherer Stress: An Example from Prehistoric South and Southwest Texas. Unpublished M.A. thesis, University of Sheffield, United Kingdom.

Broehm, Cory J. and Troy R. Lovata

2004 Five Corner Tang Bifaces from the Silo Site, 41KA102, a Late Archaic

Mortuary site in South Texas. Plains Anthropologist 49(189):59-77.

Lovata, Troy R.

1997 Archaeological Investigations at the Silo Site (41KA102), a Prehistoric

Cemetery in Karnes County, Texas. Unpublished M.A. thesis, Department

of Anthropology, University of Texas at Austin.