Berger Bluff

The paleoenvironmental record of this site in the eastern South Texas Plains provides an extraordinarily detailed look at the early Holocene climate and ecological setting of Coleto Creek, a major tributary of the Guadaulpe River. Berger Bluff appears to have been a base camp during the Late Prehistoric and Late Archaic, occupied at least seasonally by a small band of people. But the site is remarkable for what has been learned about its earlier evidence of past environmental conditions which archeologists were able to discern from the remains of small animals such as snails. Different species of snails thrive in different environmental conditions, and by determining which species were present at the site at a given time archeologists have reconstructed what the climatic conditions were like. At Berger Bluff this evidence indicates that the climate was moist and cool until about 8,000 to 10,000 years ago, when the change to a more modern climate began.

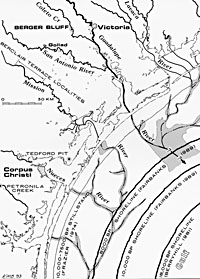

The site is a nine-meter (30 feet) high sandy bluff on the southwest side of Coleto Creek, which forms the northeastern boundary of Goliad County here. The city of Victoria lies about 15.5 km (9.6 miles) to the east. The entire bluff is an exposed archeological site. The uppermost 2.5 m (8.2 feet) of deposits were excavated in the summer of 1979, approximately the lowest 2 m (6.6 feet) were tested during field visits between November, 1979 and April, 1980, and the middle package of sediments, about 4.5 m thick (15 feet), have never been investigated.

Chiefly in the upper 45 cm (1.5 feet), artifacts and animal remains from the Toyah Phase (radiocarbon dated elsewhere in south Texas at 1300-1600 A.D.) and the Austin Phase (about 800-1300 A.D.) were found. Toyah Phase artifacts include Perdiz arrow points and preforms, a few pieces of plain bone-tempered pottery, a core, and preforms for thinned bifaces. Austin Phase artifacts include Scallorn arrow points, Darl points, thinned bifaces, and a core. Snail and freshwater mussel shells are found throughout but are especially abundant in the Austin Phase midden, where at least seven species of mussels and nine of land snails were found. Most of the mussel shells are atypically small, either because of collecting pressure or frequent washouts in the creek. Vertebrates (about four dozen kinds) are also abundant in both of these Late Prehistoric phases and include gar, white-tailed deer, pocket gopher, eastern mole, eastern cottontail, cotton rat, soft-shell turtle, wood rat, red-eared turtle, jackrabbit, opossum, Western diamondback rattlesnake, bison, and many other kinds of mammals, reptiles, birds, and fish.

Below this are Late Archaic deposits with a few Ensor (200 B.C.-600 A.D.) and Morhiss dart points, along with other thinned bifaces, biface preforms, cores, hammerstones, ground sandstone, modified flakes, chipping debris, snails, and mussel shells. Very little animal bone survives in these older deposits, only white-tailed deer and fish having been recognized. Features of probable Archaic age include two small clusters of fire-cracked sandstone and a small pit with dark fill. The lower part of the blufftop excavations has sparse cultural debris and mussel and snail shell of unknown age, perhaps Middle Archaic.

The lowest part of the site is an erosional shelf or bench at the foot of the bluff. During the relatively wet climate of the Late Pleistocene and early Holocene, groundwater emerging from buried Goliad Sandstone bedrock dissolved calcium carbonate from the rock, precipitating it in the adjacent floodplain sediments. The sediments themselves were more silt- and clay-rich than the overlying sediments, because flooding was more prolonged and less violent in this early period. The clay, silt and carbonate formed a cohesive mass that resisted later erosion, and it also helped preserve a wealth of (mostly small) biological remains that tell us something about past environments. Sometime early in the Holocene, carbonate deposition was greatly curtailed as progressive drying of the environment reduced groundwater. Flooding became less prolonged and more flashy, and floodwaters carried less clay and silt. As a result, Holocene sediments above the bench are much more easily eroded.

Eleven radiocarbon assays have been done on charcoal or sediment organics, but all come from the middle part of the bench deposits, where the most reliable assays seem to fall mostly into the Folsom and Late Paleoindian time span. There are no assays from the top or bottom of the bench but the time span as a whole is guessed to be about 7600-11,000 B.C. This time includes the Younger Dryas, a cold period that interrupted the warming climate at the end of the Pleistocene, and the Preboreal, the first climatic phase of the Holocene.

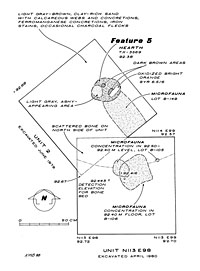

Excavations uncovered three cultural features in the bench deposits: a small hearth (a patch of fire-baked floodplain matrix) and two small pits of unknown function. Chipped stone is present, but is sparse and undiagnostic. A small in situ (in place) scatter of flakes and flake fragments left from reduction of a chert cobble might be considered a fourth feature. A small, nondescript, triangular biface preform, a small conical core, a possible chopper, and a handful of flakes or flake fragments are present.

The same carbonate that weakly cements the bench deposits has helped preserve the remains of biological organisms. Three species of freshwater mussels, some tiny peaclams, silica spicules from freshwater sponges, 65 or more different kinds of diatoms (both aerobic and aquatic), about 35-36 species of snails (terrestrial, amphibious, and aquatic), and bone fragments from about 31 kinds of vertebrate animals were recovered. There are also unidentified phytoliths (microscopic silica bodies, mostly from grasses), microscopic cysts from chrysophytes (a kind of golden brown algae), small bits of charcoal from at least four kinds of trees, a tiny fragment of some unidentified charred monocot, a small piece of unidentified resin, some seed coats from hackberries, and thousands of rhizoliths (carbonate encrustations on unidentified plant roots). A single fire-baked mud dauber nest was also found. Unfortunately, as in most south Texas sites, pollen was very poorly preserved. Pollen types from about six different kinds of trees (plus some other plants) were recovered, but the pollen is so degraded that only a scatter of grains from the most decay-resistant types is left.

Among the animals, there is only one possible extinct species�a small fragment of carapace from what appears to be an extinct giant Pleistocene tortoise (Gopherus hexagonatus). Adults had carapaces two feet long or more. The snails include Valvata tricarinata, a Pleistocene cold spring snail now extirpated in Texas by Holocene warming, Pomatiopsis lapidaria, an extirpated marsh snail, and a couple of other species that are now rare or absent because of environmental changes.

Animal bone dispersed throughout the bench includes rabbit, gopher, turtles, small fish, salamander, frogs or toads, birds, snakes, raccoon, a variety of small rodents and some other small fauna. In addition to this scattered bone, there is a concentrated bone bed next to the hearth (Feature 5) with the remains of a wide variety of microvertebrates: salamanders, eastern mole, fish, snakes, frogs or toads, gophers, birds, pocket mice, woodrats, lizards, voles, kangaroo rats, grasshopper mice, rabbits, shrews, and deer mice. In general, animals from the bench deposits are small, often fossorial or nocturnal, and include many amphibians and rodents. Many of the animals, especially the amphibians, are water-tethered: they must either live or breed in standing bodies of water. Taken altogether, the evidence from the bench deposits indicates the local environment at the end of the Pleistocene and the beginning of the Holocene was significantly wetter and subject to less temperature stress or water stress than at present, but was becoming drier over time.

During this early chapter in the site�s history, Paleoindians probably seldom stayed at the site for very long�perhaps rarely overnight�and most of the visits may have been by foraging groups of women, children, and dogs. Specialized tools (Folsom points, spurred end scrapers, radial break tools) seen at contemporary sites elsewhere seem to be absent here.

Credits and Sources

This section was contributed by Dr. Kenneth M. Brown based on his multi-year research at the site and analysis and interpretations of the site remains and reported in his 2006 PhD dissertation.

Brown, David O.

1983 The Berger Bluff Site (41 GD 30A): Excavations in the Upper Deposits, 1979. Center for Archaeological Research, University of Texas at San Antonio, Archaeological Survey Report 115.

Brown, Kenneth M.

1986 Archaeological Survey and Backhoe Testing for Flume #3 Right-of-Way at Coleto Creek Reservoir, Goliad County, Texas. Center for Archaeological Research, University of Texas at San Antonio, Archaeological Survey Report 128.

2006 The Bench Deposits at Berger Bluff: Early Holocene-Late Pleistocene Depositional and Climatic History. Unpublished PhD dissertation (Anthropology), University of Texas at Austin.

Fox, Anne A., Stephen L. Black and Steven R. James

1979 Intensive Survey and Testing of Archaeological Sites on Coleto Creek, Victoria and Goliad Counties, Texas. Center for Archaeological Research, University of Texas at San Antonio, Archaeological Survey Report 67.

|