Fort Leaton

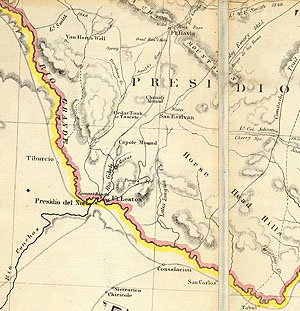

Fort Leaton is a one-acre adobe fortified compound overlooking the Rio Grande valley in Presidio County. It was once believed by some to be the site of the Spanish Mission del Apóstal Santiago, which was established in 1683, rebuilt as El Fortín de San José in 1773, and abandoned in 1810. Recent archeological investigations and archival research have since shown the site to have had a somewhat humbler and more recent beginning.

In 1832, the Mexican government awarded Lieutenant Colonel José Ygnacio Ronquillo a 6000 square kilometer (2,345 square mile) grant of land in the La Junta district. He was transferred to Baja California later that year and sold the grant to Hypólito Acosta, who sold it to Juana Padrasa in 1833. Sometime between 1833 and 1840, Pedrasa met Ben Leaton in Chihuahua, Mexico and the two became lovers. Though they had three children together, Pedrasa and Leaton never legally married.

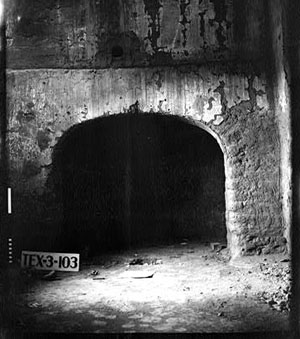

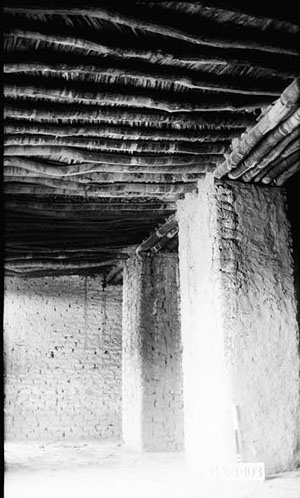

Pedrasa and Leaton moved to La Junta and enlarged their estate in 1848 by purchasing property from Juan Bustillos. Bustillos had no title to the land, so Leaton paid a government official to manufacture a fraudulent one. The men were soon found out, but the Mexican government could do nothing because the land in question was now part of the United States. Leaton expanded and fortified the existing adobe structures on Bustillos’ land into a square-shaped compound that he dubbed Fort Leaton. The 40-room fort was one of the largest adobe buildings in Texas and served as a home, trading post along the Chihuahua Trail, and private fortification for the Leaton family against Indian raids and attacks by bandits and other outlaws.

Leaton’s history at the fort was short-lived and contentious. He was accused by the Mexican government of encouraging Apache and Comanche groups to raid Mexican settlements for livestock that were then traded to him for guns and ammunition. Indian raids were nothing new in the La Junta area, however. Apache groups began conducting raids on other Indian groups and Spanish settlers in the Big Bend region in the early 1700s, and Comanche groups were actively raiding by the mid-1700s. It was also not unusual for these Apache and Comanche groups to trade with the same people that they raided.

Leaton countercharged that his Mexican accusers had endangered the lives and safety of all the settlers along the border by putting a bounty of $250 on Apache scalps and hiring Anglo outlaws to carry out these killings. This practice was intended to reduce Indian raids into Mexico, but had the opposite effect. Those who participated in the scalpings were often indiscriminate and greedy, and the scalps that they presented for payment were frequently those of members of other Indian tribes or even of the Mexicans that the bounties were designed to protect. As a result, tribes that were once friendly became hostile, and Mexicans in the area became distrusting of the Anglo settlers. An investigation of the charges against Ben Leaton was ordered by Major General George M. Brooke, commander of the Eighth Department, U.S. Army, but it was cursory and inconclusive. Neither the charge against Leaton nor his counter-charge were ever substantiated.

Leaton died in 1851 from an unknown cause. Following his death, an immaculate postmortem marriage had to be performed to give Pedrasa the title of "widow" and ensure that she could inherit Leaton's estate. Padrasa soon married Edward Hall and their family continued to live in Fort Leaton and operate it as a trading post until the 1860s. The fort also served as the first seat of the unorganized Presidio County. Although Fort Leaton was not a military fort, it was the lone outpost of defense along the 720 kilometer (450 mile) stretch of the Rio Grande from Fort Duncan at Eagle Pass to Fort Quitman southeast of El Paso. Until the construction of Fort Davis in 1854, the U.S. Army made Fort Leaton its unofficial headquarters in the area.

In the 1850s, Secretary of War Jefferson Davis authorized the experimental use of camels as pack animals by the military in west Texas to determine if the animals had military applications on the arid western frontier. In 1860, Lieutenant William H. Echols was sent with 31 soldiers, 24 camels, and 25 pack mules to find an overland trail to San Carlos Crossing (Lajitas) and survey it as a possible site for a fort. The caravan stopped along the way at Fort Leaton between July 17th and 20th. When Echols reached San Carlos Crossing, he did not find it suitable for building a fort and the army continued to use Fort Leaton as an outpost for military patrols. During the Civil War, the private fortification was briefly occupied by Confederate troops.

As a result of financial difficulties, a mortgage on Fort Leaton and the surrounding property was foreclosed on by John D. Burgess, the Leaton-Hall creditor, in 1862. The Burgess family expanded the fort during their ownership, and, despite the murder of John Burgess by a vengeful William Leaton in 1875, continued operation of the trading post until 1884. By that time, railroads had been constructed that linked San Antonio with the Gulf Coast, El Paso, and Mexico City, effectively closing the Chihuahua Trail. Presidio’s heyday as a major port of trade was over, and business at Fort Leaton greatly diminished. Furthermore, Indian raids had declined across much of west Texas by the mid-1870s and ceased altogether after 1880, ending the military’s need to use Fort Leaton as an outpost.

After the Burgess family ceased to occupy Fort Leaton in 1884, the fort began to deteriorate. For the remainder of the 19th century and the first quarter of the 20th century, Fort Leaton was occupied periodically by several tenant families. Members of the Burgess family may have added an adobe chapel to the grounds of Fort Leaton sometime in the early 1920s, but they sold the property in 1925. Between 1927 and 1956 various rooms of the fort were used sporadically as living quarters or for storage.

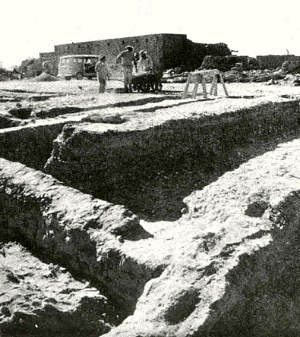

The first restoration of the main fort structure was attempted by Alice Jack Shipman in 1936. This effort lasted for over four months and consisted of replacing large quantities of adobe, removing and restoring ceilings, and applying plaster to both the interior and exterior of the fort. Later that year, an Historic American Building Survey was completed for the fort and State of Texas historic monuments were erected on the site. Excavations and measured drawings of Fort Leaton were completed by the Works Progress Administration (WPA) in 1940. The WPA may have also been responsible for renovations to the chapel.

Texas Parks and Wildlife Department (TPWD) acquired Fort Leaton in 1967 and produced a historical preservation plan for the site in 1974. Excavations by Edward Jelks and Dessamae Lorrain during an Illinois State University field school in the late 1960s identified three major building phases at Fort Leaton, based on differences in the content, and the overall size and shape of the adobe bricks used to construct the fortification. The earliest of these building phases, based on the artifact assemblage recovered by Jelks and Lorrain and subsequent TPWD archeologists that worked at Fort Leaton in 1971 and 1973, probably dates no earlier than 1820 or 1830.

Today, visitors to Fort Leaton State Historic Site can picnic, take guided tours, and view exhibits on the cultural history, natural history, and archeology of the area. On weekends during the school year, docents from Presidio High School dress in period costumes and provide guided interpretive tours of the fort. Folklorico dancers of all ages often perform during special events. Viewers may contact the staff at Fort Leaton (432-229-3613) or visit the Fort Leaton State Historic Site website for more information about events held at the site. The site is open from 8:00 a.m. until 4:30 p.m. seven days a week, except for Christmas Day.

Contributed by Tim Roberts.

Sources

Applegate, Howard G. and C. Wayne Hanselka

1974 La Junta de los Rios Del Norte y Conchos. Southwestern Studies Monograph No.

41. Texas Western Press, The University of Texas at El Paso.

Cloud, William A.

2004 The Arroyo de la Presa Site: A Stratified Late Prehistoric Campsite Along the Rio

Grande, Presidio County, Trans-Pecos Texas. Report prepared by the Center for Big

Bend Studies, Sul Ross State University, Alpine, Texas, for the Texas Department of

Transportation, Austin.

Echols, William H.

1861 Report. In: United States, Thirty-sixth Congress, Second Session, Senate Executive

Document, No. 1. Washington, D.C.

Ing, J. David and George Kegley

1974 Archeological Investigations at Fort Leaton Historic Site, Presido County, Texas, Spring 1971. Texas Parks and Wildlife Department, Austin.

Jones, Oakah L.

1991 Settlements and Settlers at La Junta de los Rios, 1759-1822. Journal of Big Bend

Studies 3:43-70.

Kelley, J. Charles

1952 Factors Involved in the Abandonment of Certain Peripheral Southwestern

Settlements. American Anthropologist 54(3):356-387.

Morgenthaler, Jefferson

2004 The River Has Never Divided Us: A Border History of La Junta de los Rios. University of Texas Press, Austin.

Texas Parks and Wildlife Department

1974 Preservation Plan and Program for Fort Leaton State Historic Site, Presidio

County, Texas. Report prepared by the Texas Parks and Wildlife Department, Austin.

|

View looking into the Fort Leaton compound, now a state historic site. Photo courtesy Texas Parks and Wildlife Department. View contemporary floor plan |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|