Climatic Trends

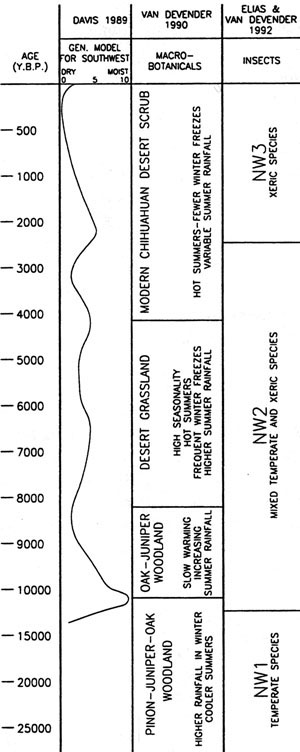

The dry-wet climatic trend curve shown on the Prehistory page is based on a general model for the American Southwest created by Davis (1989). Overall, throughout the 13,500-year span of known human occupation, the Trans-Pecos has experienced a gradual warming and drying trend with periodic fluctuations back toward wetter and somewhat cooler conditions. Like all general climatic models, the overall trends through time mask countless short-period oscillations—droughts and wetter-than-average periods lasting years and decades—the on-the-ground patterns that humans have to deal with season to season and year to year. Because a good deal of research has been done in Trans-Pecos and adjacent areas of the Southwest, its past climate is fairly well understood, at least in broad stroke. Numerous lines of evidence have been used by researchers to reconstruct ancient environments in the Trans-Pecos. Most are based on measuring “proxy” variables—things that are thought to indirectly reflect ancient climates. For instance, extended wet periods favor the growth and expansion of woodlands and an overall higher biomass, while dry periods are marked by lower biomass and the expansion of contrasting vegetation patterns, such as grasslands and scrublands. By calculating the relative frequencies of different kinds of pollen or animal bones, scientists can see trends through time and make educated guesses about climatic trends. Thus, plant and animal remains are examples of proxy variables that indirectly reflect climatic changes. Interpreting these data is very tricky, however, as many factors can affect their preservation and distribution. One of the most important sources of these proxy variables for researchers working in the Trans-Pecos has been packrat middens. Packrats will collect most anything within their territories that they can carry back to their dens. Though they predominantly collect vegetation, they will bring back rocks, animal bones, insect parts, and other small objects which they use to form very durable nests cemented by packrat urine and feces. These packrat accumulations, or middens, are often preserved in dry areas such as the Trans-Pecos, sometimes for tens of thousands of years. When scientists analyze the contents of these middens, they can determine what plants and animals were living in the vicinity at the time that the nests were created. The chart to the right (adapted from Abbott 1996) depicts a longer and more-detailed climate history of the Trans-Pecos, based on data from several proxy sources. The first column again shows Davis’ dry-wet climatic trend curve for the Southwest as a whole. The second column, based on Van Devender’s 1990 study of packrat middens, describes the changes in vegetation, temperature, and rainfall pattern that have accompanied this drying trend. The third column, based on Elias and Van Devender’s 1992 study of insect remains from the Big Bend region, shows the change in insect species that occurred during this time. These lines of proxy evidence, along with other studies, such as Wells’ 1966 study of packrat middens in the Big Bend, Hoyt’s 2000 Ph.D. dissertation analyzing pollen from a wetland in Pecos County, and Bartlema’s 2001 Master’s thesis studying fauna from a cave in southern New Mexico, can be used to create a climatic sequence for the last 14,000 years in the Trans-Pecos. |

|

During the last ice age the lowlands of the Trans-Pecos were covered with a piñon-juniper-oak woodland and mesic (moist) woodland trees, such as Douglas fir and Rocky Mountain juniper, grew on the mountains. Around 14,000 years ago xeric (dry) plants, such as mesquite and sotol, began to invade the piñon-juniper-oak woodland and the mesic woodland trees retreated up the mountain slopes. Between 10,000 and 9,000 years ago the piñon-juniper-oak woodland retreated up the mountain slopes and replaced the mesic woodland species, while a desert grassland spread across the lowlands. By 4,000 years ago the desert grassland was replaced by the modern scrubland of the Chihuahuan Desert. Relicts of the piñon-juniper-oak woodland exist today in isolated patches at high elevations in the mountains. Keep in mind that this climatic sequence just describes long-term climatic trends. All Texans, especially those living in the western half of the state, are familiar with short-term droughts lasting months or years and the less common unusually wet years (like 2007) that affected much of the state. While people mainly react to short-term climatic events and fluctuations, many prehistoric cultural patterns represent long-term changes (adaptations) over many generations. As the climate becomes progressively drier, for instance, some formerly dependable food resources become less numerous, and people are forced to either move or learn to depend on what is available. It is also likely that higher human population densities were possible during more favorable climatic periods. Prehistoric peoples sometimes coped with less favorable periods by adopting new strategies for making a living. For instance, a distinct prehistoric pattern is the greater reliance through time on labor-intensive earth-oven baking of marginal plant resources like bulbs and roots, foods that are and were much less desirable than deer, nuts, and fruits. ReferencesAbbott, James T. Bartlema, Lauri L.L. Davis, O.K. Elias, Scott A. and Thomas R. Van Devender Hoyt, Cathryn A. Riskind, David H. and Thomas R. Van Devender Wells, Phillip V. Van Devender, Thomas R. |