Skeleton on La Belle: Tracing the Life of a French Sailor

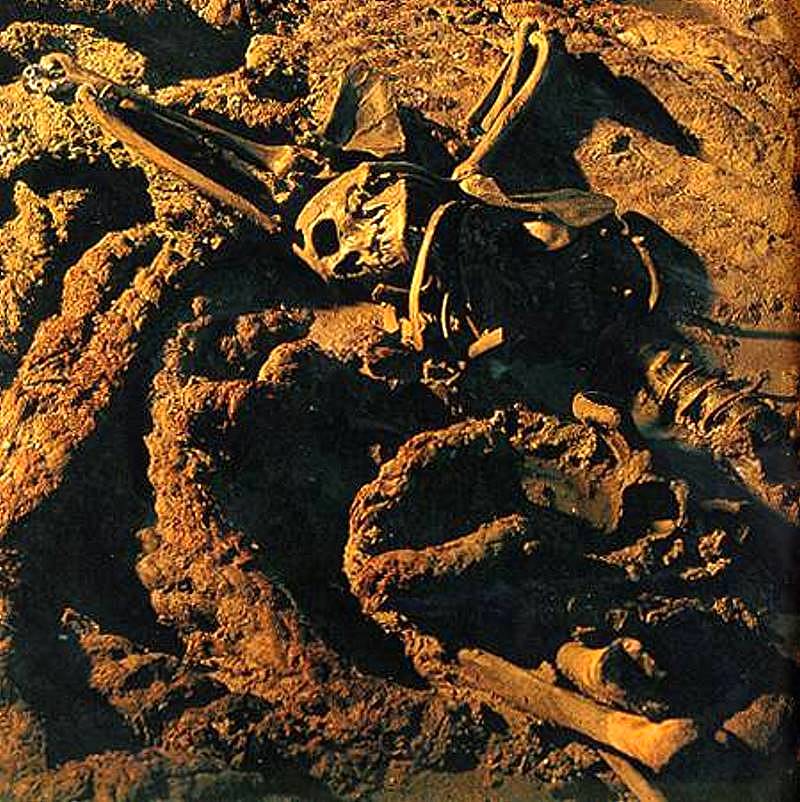

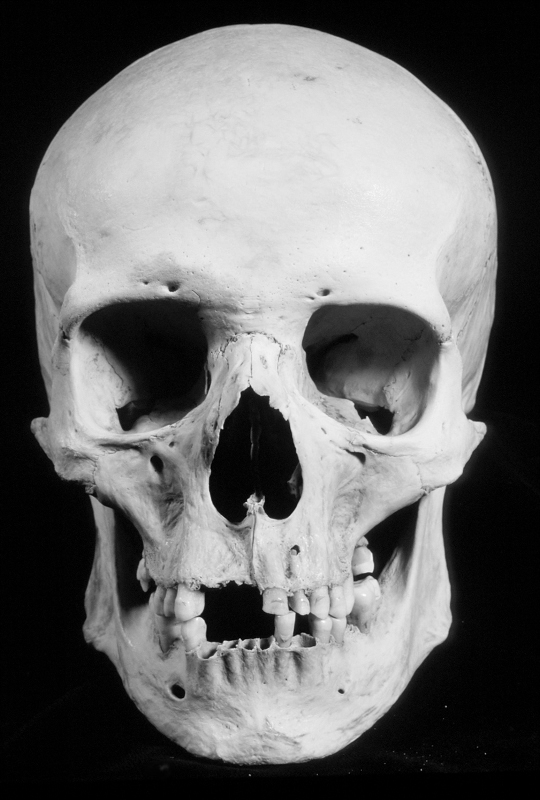

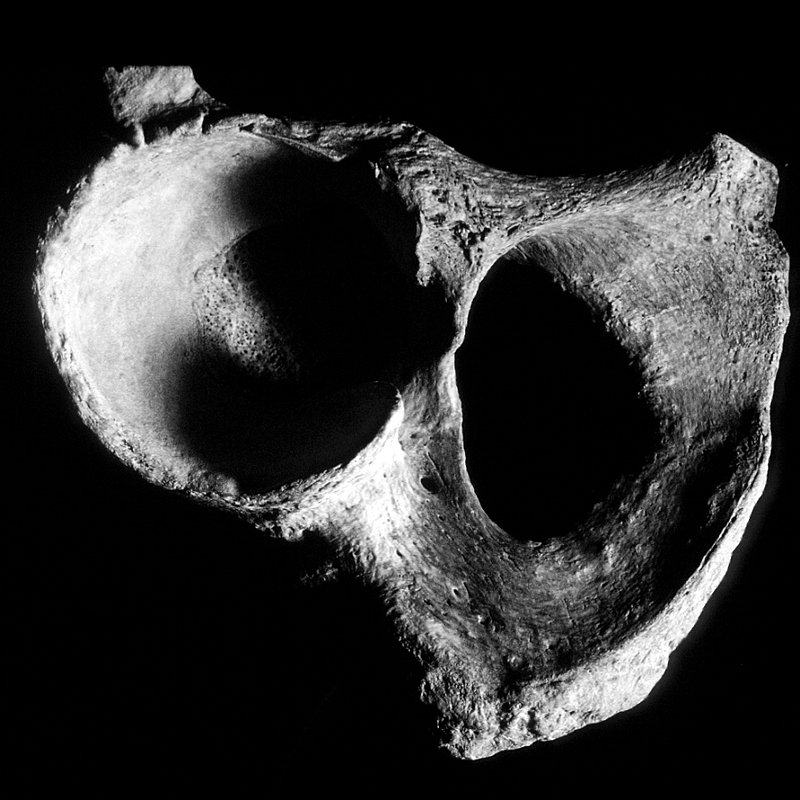

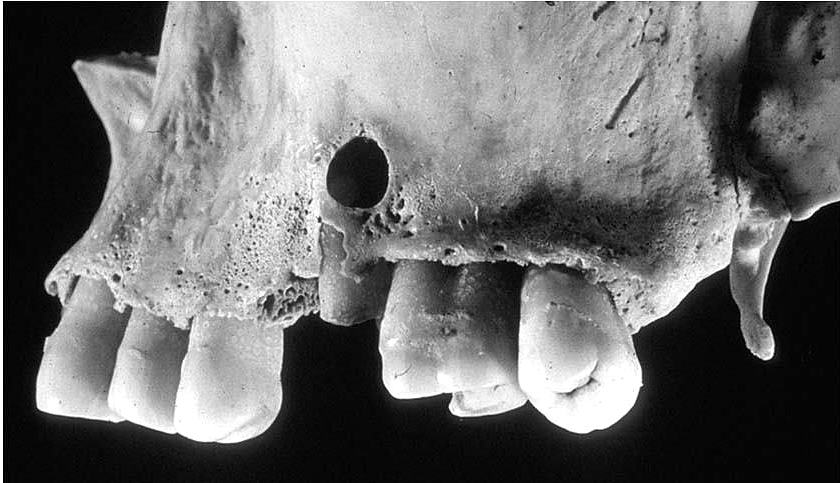

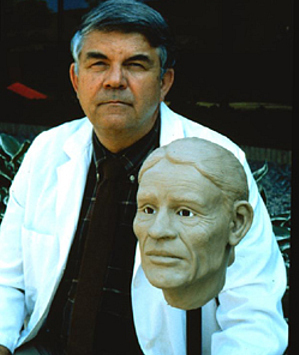

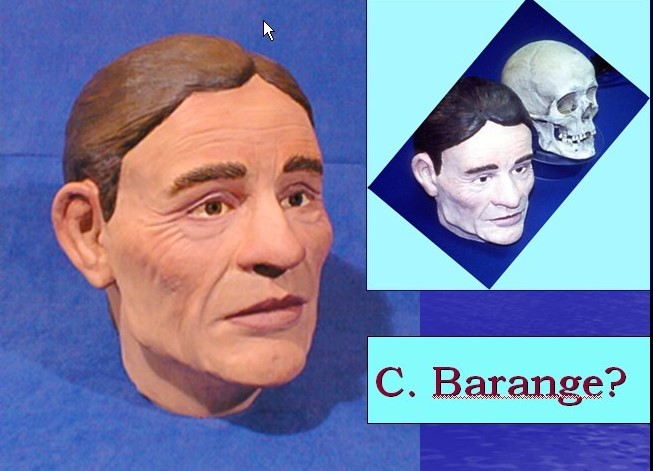

One of the most startling discoveries during the excavation of La Belle was a human skeleton in the bow section, or forward hold of the boat. Lying face down, with arms and legs drawn up, the individual was splayed over a coil of anchor rope. Near him were a leather shoe, a small wooden cask, a leather wallet with two combs inside, and a pewter cup bearing the inscription, “C. Barange.” Buried for nearly 300 years beneath Matagorda Bay, the skeleton was still articulated and in a remarkable state of preservation, due to the anaerobic, or oxygen-free environment within the silty sands. Bits of tendon still clung to the bone, and a large part of the brain remained intact inside of the skull. Hopes were high for what could be learned about the individual who had journeyed to the New World with La Salle. The discovery of human remains was particularly poignant for the archeologists working on the recovery of the ship and its cargo. As principal investigator James Bruseth notes in From a Watery Grave, “It is one thing to find objects the colonists brought with them from Europe. It is quite another to recover the actual remains of the people themselves. Finding the bones made us feel a very personal connection with La Salle’s colonists and appreciate their misfortune even more.” The skeleton was carefully removed from the wreck and sent to the Conservation Laboratory at Texas A&M University where it was slated to undergo a series of analyses. The questions were many: Who was the individual? Was he C. Barange, as the cup found near him suggested, and could his DNA be traced to living members of this family in France? How old was he? What had his life been like? What did he look like? And finally, how did he die? Analysis of the RemainsPhysical Anthropologist D. Gentry Steele of the Texas A&M University Department of Anthropology volunteered his time to perform the skeletal analysis and help answer these questions. Because even small elements such as the wrist bones and hyoid had been recovered, Steele knew that the body had decomposed in the position in which it was found. Water action had not washed these tiny bones away, nor had sea creatures scavenged or disturbed them. It appeared the body had been quickly covered over and protected by sediments, all except for a portion of its right side. Barnacles had attached to some of the arm and leg bones—the right humerus, ulna, and femur—suggesting exposure to sea water for some time. Based on the skeletal information alone, Steele could not determine, however, whether the body had floated into the bow of the ship, whether the corpse of the individual had been placed there prior to the wreck, or if the man had been alive when he entered the bow. Analysis of the skeletal elements provided more information about the age and physical appearance of the individual. Based on measurements and growth indicators and using statistical comparisons, Steele determined that the individual had been a stout and muscular male of European descent. He stood somewhere between 5 feet 3 inches to 5 feet 7 inches tall—the average height for 17th-century Frenchmen—and he was between 35 and 45 years old at the time of death. Life had not been easy for La Belle’s sailor, however. Although he showed no signs of fatal trauma or disease, he had suffered a number of injuries in his lifetime and considerable pain from medical disorders, including severely abscessed teeth and infected gums. At some time well before his death, his nose had been broken, and the injury had healed. Although the cause is not known, the force struck the left side of his face, breaking his left nasal bone and causing significant damage to the soft tissue as well. According to Steele, this pattern of trauma commonly occurs when a right-handed assailant strikes an opponent he is facing on the left side of the face. Whether the sailor was involved in a fist fight or whether his nose was broken in a fall or accidental blow will continue to be a mystery. The individual also walked with a limp, and suffered acute pain in his lower back, hips, and legs based on a variety of disorders detected in those regions. Nodes on two of the thoracic vertebrae likely were caused by compressed disks, and other damage suggested herniation of one or more of the disks. These conditions may have resulted in pinched nerves. There was a high degree of stress evident in the junction of the spinal column to the hip that had been created by a variety of disorders in the hip region. This stress was also indicates in enlarged and worn hip sockets condition also was indicated by the enlarged hip sockets. All of these disorders likely resulted in a reduced range of movement in the lower back and uneven tilt to the hip, producing an uneven gait and stance. The legs also showed evidence of injuries and medical stress. Bone spurs were present on the lower right leg, where the calf muscles emerged below the knee. These may have been caused by stress from the individual’s uneven gait, or a separate injury. There was also evidence that the individual had suffered a sprained ankle. DentitionAn examination of the dentition of the sailor revealed another source of pain in his lifetime. In addition to missing several teeth, he had numerous severe cavities and abscesses that had eaten away a hole in his maxilla, or upper jaw. During his lifetime, he had lost four molars and he had severe cavities in two other molars. The crown was missing from one molar, leaving only the roots which had become blackened, and the second molar retained only a portion of its crown. The remaining functional teeth showed considerable signs of wear, having had the full load of chewing shifted to them. Steele noted one particularly unusual pattern in the upper canines and incisors. Heavy wear had created an arc-like pattern in the margins. The incisors and canines were canted downward in an abnormal pattern indicating that they may have been used as tools particularly in tasks involving shredding of fibrous materials, such as rope. Perhaps the sailor had used his teeth to hold rope. The incisors also had specific growth arrest lines showing that the individual had been through at least two periods of illness or inadequate diet, which had halted their growth. Based on the position of the lines on the teeth, this likely occurred when the individual was very young, during weaning. Reconstructing the FaceA series of procedures was undertaken to try to determine what La Belle’s sailor looked like. First, an exact replica of the skull was made using stereo lithography. The skull was scanned through a CT (computer tomography) scanner at the Texas Scottish Rite Hospital for Children in Dallas to obtain detailed, 3D digital images of all the diagnostic features. The scan also revealed how much of the brain was preserved inside the skull. At CyberForm International in Arlington, Texas, the digital data was then used in a casting process known as stereolithography to create two resin replicas of the skull. Finally, with information about the sailor’s age, stature, and ethnicity derived from the skeletal analysis, Denis Lee of the University of Michigan began to reconstruct the details of the face. A medical illustrator, Lee had tackled a number of similar facial reconstructions in the past, including that of the 11,000-year-old woman nicknamed “Leanne,” excavated from a burial at the Wilson-Leonard site near Leander, Texas. Lee applied bits of clay to the resin cast of the skull, shaping it to match facial muscles, then added another layer of clay to simulate skin. Applying skin color, hair, and eye color was conjectural, as there is no way to know these attributes based on skeletal remains. It is likely, however, that the sailor, having experienced considerable hardship and months at sea, would have appeared weathered and gaunt, with unkempt beard and hair. Lee’s final mold was painted without facial hair in order to show the features of the face, perhaps as the sailor may have looked as he embarked from France in 1684. The Sailor’s FateFor researchers, other questions remained to be answered: Who was the sailor on La Belle? Archeologist James Bruseth, who had overseen the skeleton’s excavation, had hopes that, with viable DNA samples, the sailor’s identity might be tracked in France. He had located numerous individuals with the name, Barange, living in Rouen, the port city from which La Belle set sail more than 300 years ago. The plan was to compare the gene profile of the Belle sailor with that of modern members of Barnge families, hoping to find connections. At the A&M lab, samples were taken from the brain, as well as from several bones and teeth. Analysis began. But a host of tiny sea creatures brought the search for the sailor’s identity to a halt. Even though the skeleton was well-preserved and had been covered by sediments in the bay, marine micro-organisms had moved into the bone and brain, contaminating the DNA. Analysis would have revealed their genetic profile, not that of the Belle’s sailor. Nonetheless, researchers hold out hope that new techniques in the future may coax usable DNA from the remaining samples reserved for that purpose. A final question regarding the skeleton, then, is: How did the sailor die? Analyst Steele found no evidence of disease or trauma serious enough to have caused the man’s death. Indeed, the condition of the skeleton indicated that the man had been in relatively good health, with the exception of having very bad teeth, arthritis and other joint problems. Rather than finding clues from the bones, the answer to this question may lie in an historic journal kept by one of La Salle’s most trusted companions, Henri Joutel. As the ship lay wrecked on the sandbar in the days following the storm, Joutel wrote, conditions became increasingly desperate. Although they were only about a quarter mile from shore, few sailors knew how to swim. A small boat with five men was sent ashore to obtain fresh water, but the men never returned and were presumed drowned. The lack of water added to the loss of the five best men on board forebode a deadly end for the survivors. Meanwhile, they stayed a few more days in the same place waiting to learn something. During this time, several people among them died from a lack of water.

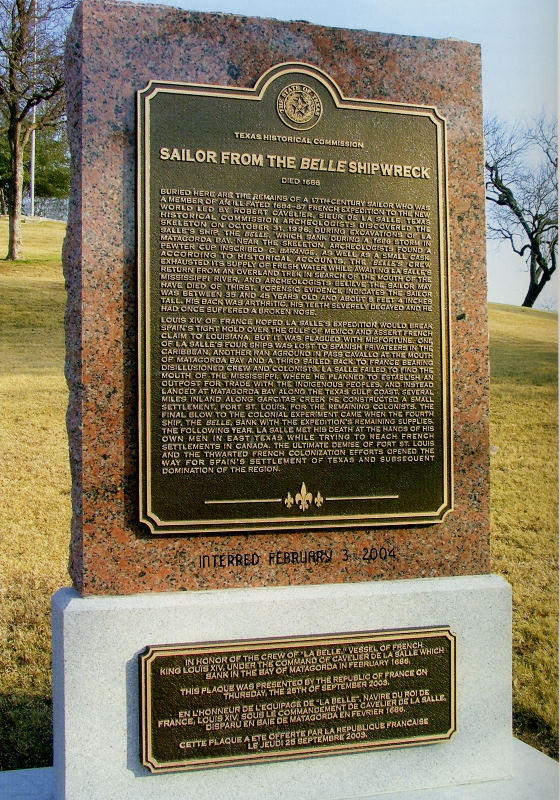

Of the original 27 people assigned to stay on board the ship, apparently only six survived. With the captain, who had been drinking brandy for days, they finally made it to a small peninsula where they set up camp. Over the next several weeks, La Belle sunk further into the bay, taking with it, the body of the sailor. On February 3, 2004, the sailor’s remains were buried in the Texas State Cemetery in Austin. The French ambassador to the United States and the Texas Secretary of State were in attendance, along with some 400 members of the public. To learn more about the burial service for La Belle’s sailor, see “Belle Sailor Honored at Special Funeral” www.thc.state.tx.us/lasalle/lasburial.shtml.

|

|