Diet and Health: Bioarcheology of the Early Texas Coastal Plain

The physical remains of past peoples can provide a wealth of information regarding the interaction of health and disease. By studying human skeletal remains, an understanding can be gained about how our species has adapted to environmental challenges across time. The people who inhabited the Texas Gulf coast and associated coastal plain can tell us much about how they lived, subsisted, and survived in an ever-changing world. If we can understand the past interactions between human beings and their environment, then we can prepare for future challenges to human health in a dynamic world.

The Texas Gulf coastal plain provides a unique opportunity to study past human disease. Sites like Ernest Witte, Morhiss, McNeil-Gonzales, Crestmont, Loma Sandia, Mitchell Ridge, Harris County Boys School, and others have given a wealth of information about how peoples of the past lived and adapted to the challenging environment of the coastal plain. A synthesis of data from these sites reveals that these early peoples were generally healthy and well-fed, but occasionally suffered from chronic or degenerative conditions that negatively impacted their health.

Disease and Human Skeletal Remains

To understand the past interactions between hunting and gathering peoples and disease, one is confined to two areas of research. The first line of research is the study of human remains, usually skeletal lesions on bone. Bone, like any other tissue of the human body, is subject to outside stimulus. Unlike other tissues of the body, bone continuously regenerates. This process, called remodeling, replaces “old” bone with “new” bone, thus maintaining mechanical strength.

Skeletal tissues react to external stresses in one of three ways. First, new bone can be laid down to strengthen existing structures. Second, bone can be taken away (commonly referred to as osteoporosis). The third reaction is that bone can be both added and taken away. This is the most uncommon reaction of the three, but it can occur, particularly in a disease process.

Bone’s limited reaction to disease can create problems of interpretation. Many viruses and some bacterial infections progress quickly through the body, and kill the host before bone can react to it. For this reason, bone leaves an incomplete record of an individual’s health. Diseases that leave lesions on bone are usually chronic bacterial infections, vitamin deficiencies, and degenerative conditions like arthritis. Other conditions, such as bone fractures or joint dislocations, will also be apparent on the skeleton. This type of information also can provide insights into Native society. At the Harris County Boys School, analysis of the skeleton of a 22-25 year-old male indicated he had lost the use of his right arm and leg several years before his death. Yet the fact that he was able to survive among mobile hunter-gatherers for after he was injured shows he was cared for by members of his group.

The second area of research is the study of etiology, or the process of disease. By understanding the disease process in historic hunting and gathering populations, one can understand which diseases likely affected the people of the Texas coastal plain. Hunter-gatherers generally live in small bands or groups and population densities are usually low. This means that many communicable diseases do not affect hunter-gatherers because there are not enough people for the disease to spread. This does not mean they lived in a disease-free environment. Early inhabitants of the Texas Gulf coast would have occasionally suffered from common bacterial infections, broken bones, food poisoning, internal and external parasites, and zoonoses (animal diseases acquired by eating tainted meat).

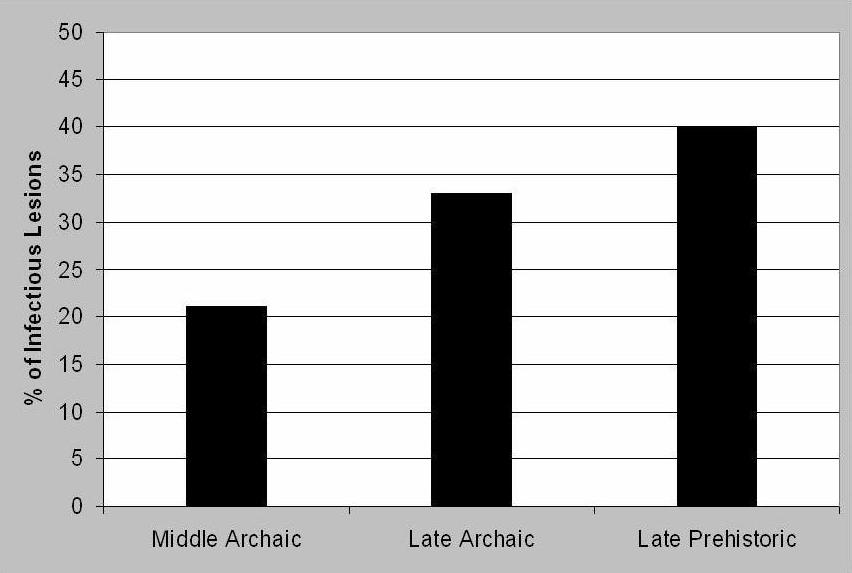

As the population grew on the Texas coastal plain, so did the frequency of diseases. The number of skeletal lesions observed in these populations increased dramatically from the Archaic periods up to the time of contact with Europeans. The chart above is a compilation of infections lesions from various sites and shows how they changed across time. This trend also is particularly well demonstrated at the Mitchell Ridge site near Galveston, where bioarcheological and mortuary evidence suggests that the Native populations of the upper Texas coast were severely impacted by European-introduced diseases even during the Protohistoric, a period during which there was minimal contact between Indians and Europeans. By the Early Historic period (1700s), the average number of persons buried in a single grave at the site increased around threefold over the Late Prehistoric, to 3.5 individuals per grave pit.

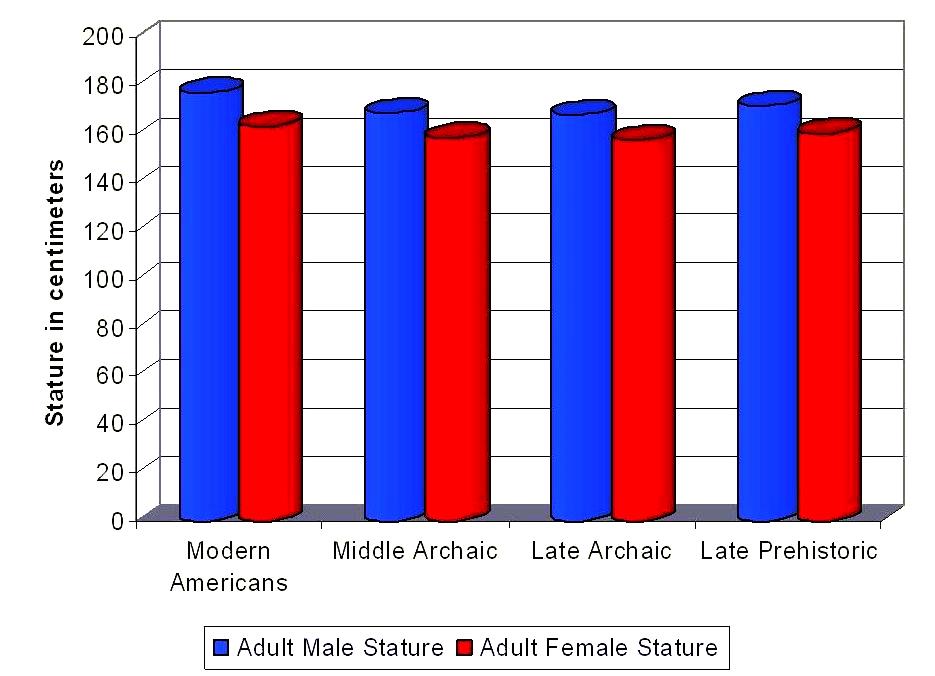

Research on recent groups (such as the !Kung of southern Africa) have demonstrated that hunting and gathering peoples are generally well nourished. This is also true on the Texas Gulf coastal plain. Early inhabitants would have eaten a broad range of plant and animal foods. This diversity in their diet, and the lack of heavily processed foods, aided normal growth and development. Adult stature can reveal the general health of a population, since underfed, sick individuals usually don’t grow to their genetic potential. By examining the adult stature of Texas coastal plain populations, one can see that malnutrition was not a chronic problem. In fact, these people were nearly as tall as modern Americans. For example, analysis of skeletons from the Caplen Mound site near Galveston, indicates that the people were well nourished, robust, tall, and experienced little chronic childhood stress. All of these factors indicate that their subsistence strategies were very successful and chronic hunger and malnutrition rare. Most individuals were able to grow to or near their genetic potential for stature.

Biological Distance

Measurements and analysis of skeletal traits (especially those of the skull) can provide information about genetic interactions of past people. Many traits of the skull and the teeth are inherited and an examination of the frequencies of those traits can reveal how closely related two populations may be. While no traits are unique to any population, the differences in how that trait is expressed can give clues about population history.

Unfortunately, biodistance research on Texas populations has been largely abandoned and early studies have not been followed up on. Some early research on Texas coastal plain research hinted that prehistoric inhabitants were somewhat distinct from other populations of American Indians. In his 1950s study, Georg Neumann remarked on the close morphological similarities between Texas coastal populations and Paleoindians. He considered the Karankawas to be a remnant population descended from the first inhabitants of North America. While this determination is probably a stretch, it does demonstrate that the Indians of the Texas coast were a unique group that warrants further study.

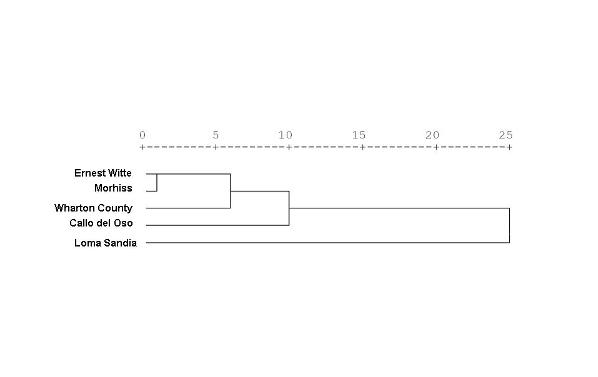

Recently, the Texas Archeological Research Lab conducted research on inherited dental traits. Five coastal plain populations were large enough to make a significant sample and statistical calculations of trait frequencies revealed some surprising results. A surprising amount of dissimilarity was found between groups in the northern part of the study area and those in the south (particularly the Loma Sandia population). As shown in the dendogram, the Loma Sandia sample is divergent from other coastal plain populations. This may mean that the Loma Sandia people were immigrants from another area or a remnant population that had been displaced from the Coastal Plain. Hopefully, this research will spur other population studies of Texas forager groups.

Contributed by Matthew Taylor.

Sources:

Armelagos, George.

1990 Health and Disease in Populations in Transition. In Disease in Populations in Transition, ed. by Alan Swedlund and George Armelagos. New York: Bergin and Garvey. p 127-144.

Jackson, A. T., Steve A. Tomka, Richard B. Mahoney, and Barbara A. Meissner

2004 The Cayo del Oso Site (41NU2): Volume 1, A Historical Summary of Explorations of a Prehistoric Cemetery on the Coast of False Oso Bay, Nueces County, Texas. Texas Department of Transportation and Center for Archaeological Research, The University of Texas, San Antonio.

Larsen, Clark Spencer

1997 Bioarchaeology: Interpreting Behavior from the Human Skeleton. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Neumann, Georg K.

1952 Archeology and Race in the American Indian. In Archeology of the Eastern United States, ed. by James B. Griffin, p 13-34. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

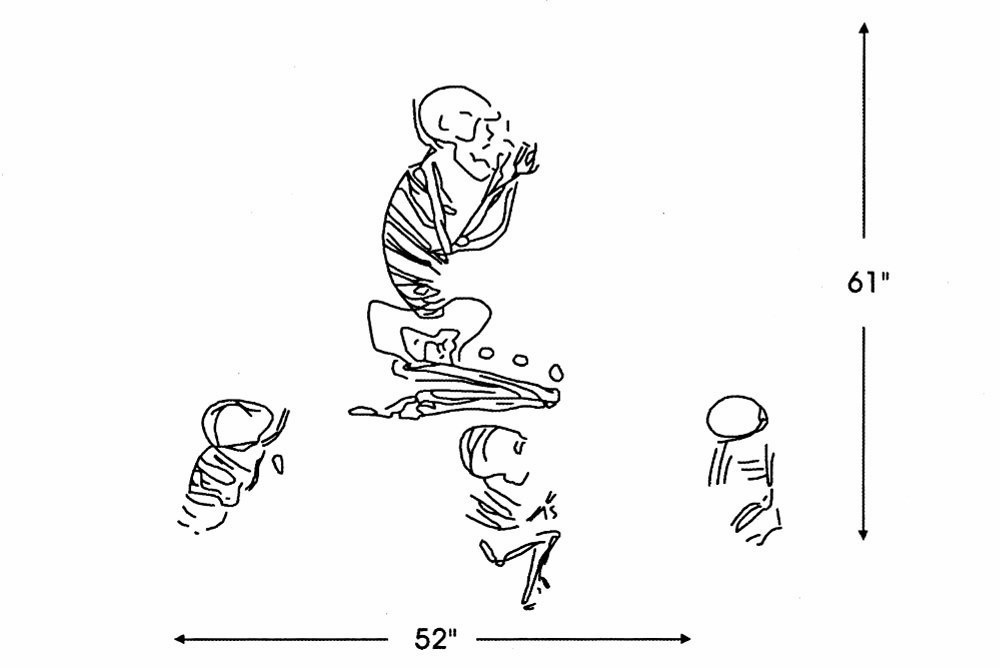

Sketch of burial of an adult female and three infants from the Cayo del Oso site near Corpus Christi, one of the largest prehistoric cemeteries in Texas. Recent skeletal analysis from this site and others in south Texas and the coastal plain have provided a wealth of information about disease patterns, nutrition, and stature in early populations. Graphic from Jackson et al. 2004, Fig. 3-13.

|

|

|

By examining the adult stature of Texas coastal plain populations, one can see that malnutrition was not a chronic problem. In fact, these people were nearly as tall as modern Americans

|

|

|