Object: Montell Dart Point

Date: 700 B.C. (2700 years ago), Late Archaic, Cibolo Subperiod

Context: Lower Pecos Canyonlands, Bonfire Shelter, Bone Bed 3

This heat-damaged Montell dart point was found in Bone Bed 3, a layer of incinerated bison bones at Bonfire Shelter which is located in the Lower Pecos Canyonlands of southwest Texas not far from the saloon in Langtry, Texas where Judge Roy Bean ruled “the law west of the Pecos” in the late 1800s. The distinctive artifact helps tell a remarkable story—almost 3,000 years ago Native American hunters orchestrated a wildly successful buffalo stampede (“drive”) causing hundreds of American Bison to tumble off a cliff into a small box canyon that drains into the nearby Rio Grande.

The story of the archeological investigations of Bonfire Shelter and its Bone Bed 3 is told elsewhere on TBH but a close look at this particular artifact and the archeological record highlights several fascinating stories, small and large.

Let's start with typology, the archeological classification of this artifact according to its physical characteristics. The iconic projectile point from Bonfire BB3 (shorthand for Bone Bed 3) is the most complete of three Montell dart points recovered from the site. Dart points (are relatively large chipped stone projectile points that were used to tip wooden darts (throwing spears) hurled with atlatls (spear throwers). See About Darts, Altatls, and Other Weapon Systems to learn more about projectile technology. The Montell dart point type is quite distinctive and easily recognizable because of its broad triangular outline and prominent central notch, creating a split stem with two rectangular tangs flanked by shorter barbs. Similar dart points have been found widely across the Lower Pecos, the Edwards Plateau and beyond. Montell points were made by hunter-gatherers who lived during the latter part of the Late Archaic period during a several-hundred-year span known in the Lower Pecos as the Cibolo subperiod, about 2600-3000 years ago (600-1000 BC).

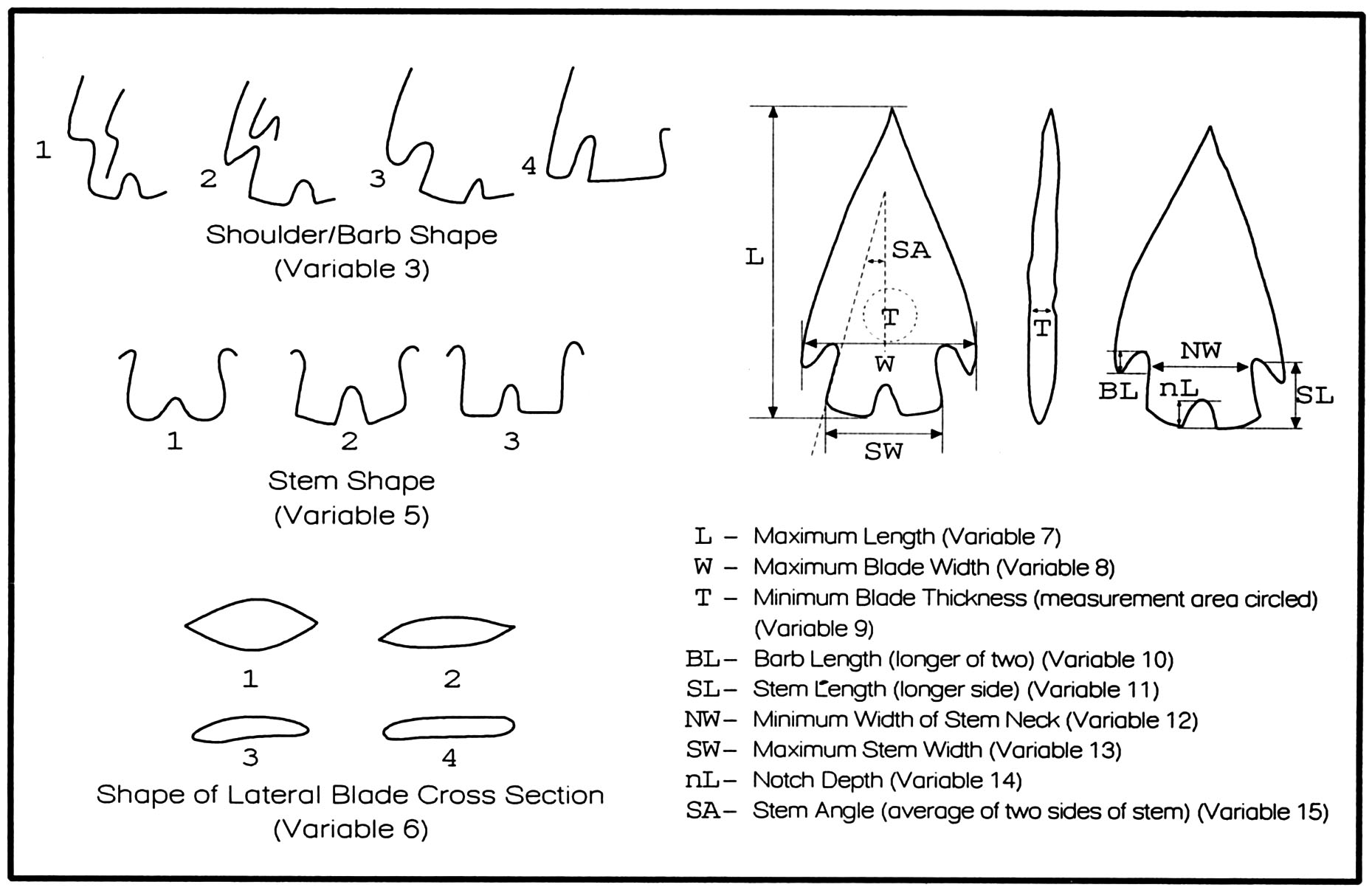

In the 1990s archeologist LeRoy Johnson Jr. carried out a detailed typological and technological study of 75 Montell points found at the Jonas Terrace site, located along the Balcones Escarpment 160 miles due east of Bonfire Shelter. Johnson measured some 15 variables (such as blade width, notch depth, stem length) and used statistics to demonstrate that Montell points were made in remarkably consistent manner. He found that skilled Late Archaic flintknappers had used antler billets (“soft hammer” technique) to remove wide, shallow “billet” flakes to create the particularly wide, thin and flat triangular blades (about 5.4 mm in maximum thickness). Johnson argued that Montell points were “part and parcel of a special bison-hunting tool kit … designed to cut wide, bleeding wounds but still penetrate game fairly deeply because of their thinness.”

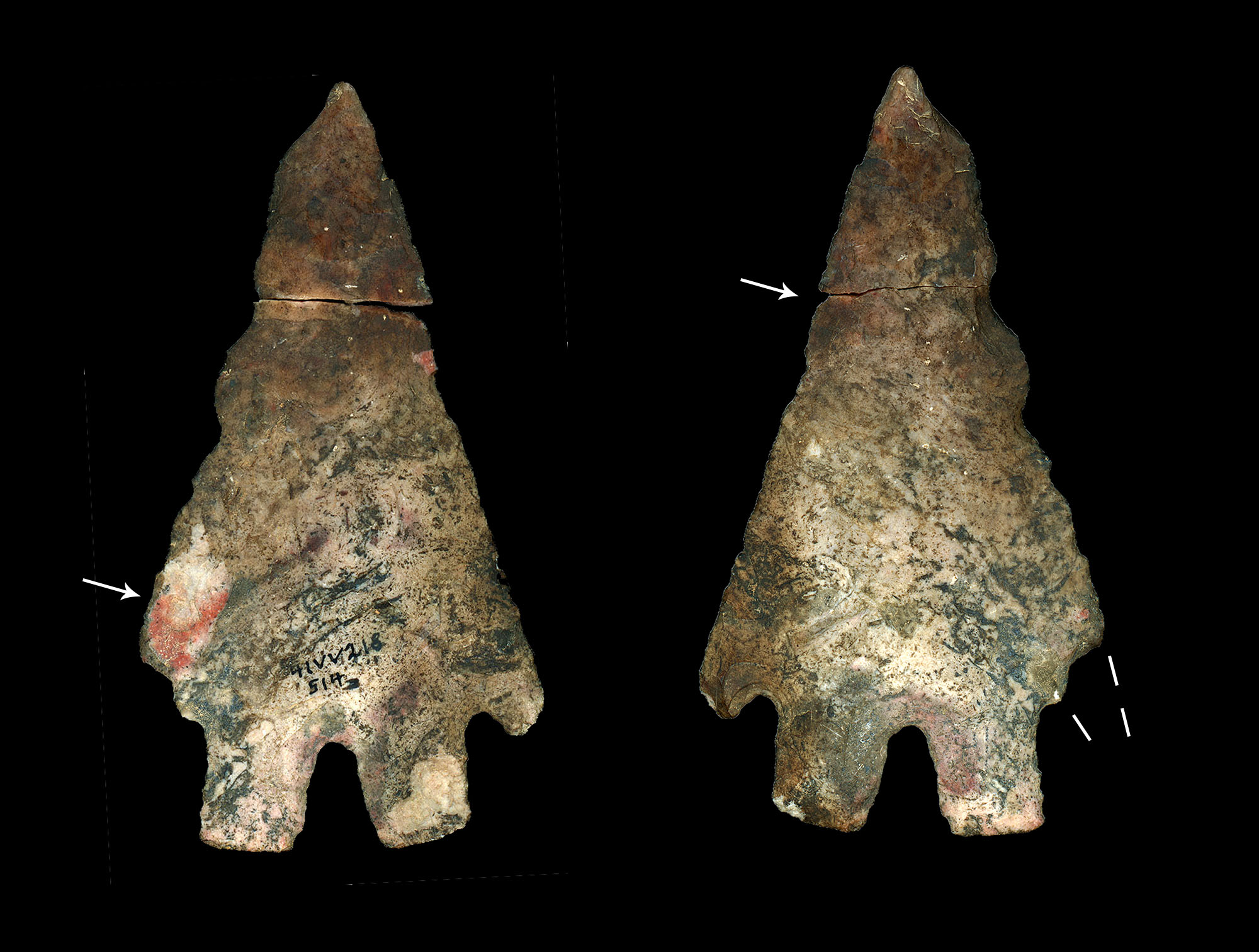

When a lithic expert adept at studying chipped-stone tools looks closely at this artifact, something of its particular life history makes itself known. Today the Montell dart point from Bonfire Shelter is in two pieces and a field photograph taken on the day it was found suggests it was already broken when found. Not quite so fast. It was likely broken when an excavator first troweled across it—even today the break is very fresh looking and not carbon-stained like the surface of most of the artifact. And centered on the break on one edge is a tiny nick, likely marking the spot the excavator's trowel struck home. This is not anything to be ashamed about—you cannot move dirt (excavate) without inadvertently striking artifacts from time to time.

Fortunately, the excavation records for this particular artifact are quite thorough. Although Dr. Dave Dibble was in overall charge of the 1963-1964 Bonfire excavations, the Montell point was found relatively late in the dig on February 5, 1964 after the main Bone Bed 3 excavations had been completed. On that day Curtis Tunnell was the field supervisor. Tunnell was then a senior archeologist on the Amistad archeological salvage program and he filled in for Dibble whenever needed. After Amistad, Curtis Tunnell went on to become the State Archeologist of Texas and then the Executive Director of the Texas Historical Commission. (The Wax Camps exhibit on TBH highlights one of Tunnell's many research projects.)

Back to Tunnell's Bonfire records. He paid particular attention to this artifact, mentioning it in the daily field journal as well as filling out a “general record form” with additional notes and an outline sketch by E.R.P—Elton R. Prewitt, a young field archeologist who went on to develop a 40-year professional career in Texas archeology. Tunnell wrote that “Carlos found the point in place (not in situ) with the tip missing. Emilio found the tip on the fine screen.” The Montell point was found in redeposited Zone II material about 6-12” below the ground surface on the outside of the talus cone where the bison fell. (Bone Bed 3 is draped over a mound of debris or “talus cone” that built up against the roof-fall beneath a notch in the cliff above the shelter. The notch formed a hidden natural barrier that caused stampeding bison to tumble down the notch and onto the talus cone where the bison carcasses accumulated.) Zone II is the stratigraphic term for Bone Bed 3. The sediments where the Montell point was found were likely redeposited by rainwater running through the notch and down the talus cone during heavy storms.

In other words, crew member Carlos Guerrero was excavating rapidly through a shallow “disturbed” deposit when his trowel hit the Montell point, nicking the edge and causing the break. He must have immediately recognized that he had dislodged the larger fragment and put it right back where he could see it came from. The dislodged tip would have been swept up in the excavated dirt and sent to the screen in a bucket. One suspects he called out to Emilio Hinojosa and warned him to be on the lookout for the missing tip, which was soon found and placed back in the ground where it should have been before the field photo was taken.

This Montell point would have broken quite easily when nicked by Carlos' trowel because it has been intensely thermally altered, meaning it was damaged by fire, almost certainly the slow “bone fire” that incinerated much of BB3 weeks or months after the kill. The intense heat given off by the smoldering fire caused two potlids (characteristic thermal spalls) to pop off the exposed surface of the artifact, one on the right-hand stem and the other on the left shoulder just above where the barb would have been. Look closely and you will see the potlid scars and notice the one on the left looks pink, so does the interior of the break—this discoloration is characteristic of thermal alteration.

Based on the above information and a few more observations, we can now recap the extraordinary story of this particular Montell dart point. It was made by an accomplished Late Archaic flintknapper around 2700 years ago (based on several radiocarbon dates from BB3 that overlap about 2600-2800 cal BP or 600-800 BC) as part of a specialized hunting weapon—a dart designed to be thrown with an atlatl. We do not know whether the hunters that drove the bison over the cliff at Bonfire were local people—they may have traveled some distance following bison herds. Regardless, we can tell that the dart point was not freshly made. Look closely at the tip and blade edges and you can see slight undulations and irregularities—these were caused by earlier use damage and resharpening (maintenance). The earlier use of the dart also resulted in the breakage of one barb, which was rounded off by retouch. Such maintenance would have occurred throughout the use lives of many artifacts, particularly a hafted dart point attached with sinew to a wooden foreshaft; retouching a slightly damaged dart point would have been much easier to accomplish than tediously replacing the haft (minutes vs. hours or even days).

The Late Archaic hunter used the Montell point one final time, likely the day of the glorious bison jump. As is known from early historic observers in the Northern Plains, bison jumps were highly orchestrated events accomplished by dozens of people working in concert. Take a look at Jack Brink's wonderful book on the famous Head-Smashed-In Buffalo Jump to learn more. We can guess that this Montell point came to rest in Bonfire Shelter after being carried there by a bison wounded by one of the hunters encircling the bison herd. The atlatl-thrown projectile would have penetrated the bison and caused considerable bleeding, but the bison likely did not meet its demise until it fell onto the talus cone.

Weeks or months after the bison jump carnage, the decaying mass of bison carcasses either spontaneously combusted or was purposefully torched. Either way, the intense fire slowly incinerated the massive deposit composed of the rotting remains of hundreds of bison and did considerable heat damage to the Montell point. Over the following decades and centuries the talus deposits gradually eroded and the artifact came to rest just under the surface at Bonfire Shelter, to be found in February 1964 as the artifact began its final transition from in-the-ground to on-the-shelf to in-the-report to on-the-internet. All in all, quite a story.

Credits

This entry was written by TBH Co-Editor Steve Black with the help of archeologist Elton Prewitt, who first handled this artifact soon after it was found. Recently (winter 2020) Elton scanned the Montell point using a flatbed scanner to obtain high-resolution, true-color images. All of the artifacts and records from the 1963-1964 excavations at Bonfire Shelter are curated at the Texas Archeological Research Laboratory on behalf of the National Park Service, who funded the excavations.

Print Sources

Brink, Jack W.

2008 Imagining Head-Smashed-In: Aboriginal Buffalo Hunting on the Northern Plains. Athabasca University Press, Edmonton, Alberta, Canada.

Dibble, David S. and Dessamae Lorrain

1968 Bonfire Shelter: A Stratified Bison Kill Site, Val Verde County, Texas. Texas Memorial Museum, Miscellaneous Papers No.1. The University of Texas, Austin.

Johnson, LeRoy Jr.

1995 Past Cultures and Climates at the Jonas Terrace Site, 41ME29, Medina County, Texas. Office of the State Archeologist Report 40, Texas Historical Commission