|

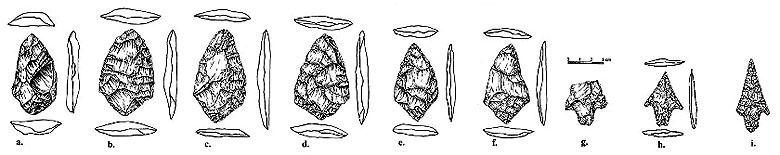

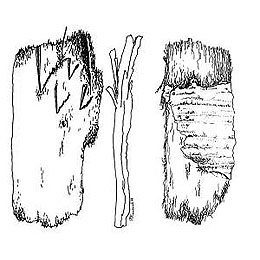

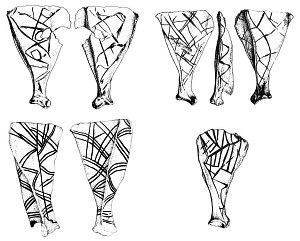

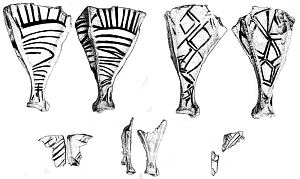

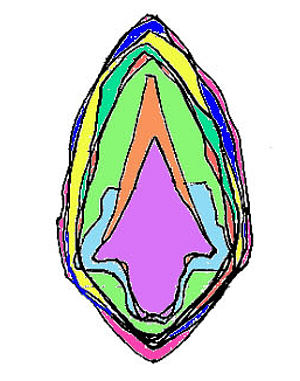

In an unpublished analysis of the lithic assemblage, researchers Lee Bement and Solveig Turpin argued that nine of the bifaces (including two dart points) represent a cache of Middle Archaic artifacts. Although the deposits had been disturbed, these artifacts appeared to have been placed in a rough circle. The cache illustrates the bifacial reduction sequence through which Langtry and Jora dart points were created. Basically, dart points are created by gradually thinning and shaping pieces of flint. Bement conceives of the reduction process as following successive stages from early to late stage preforms, to partially shaped dart point, to finished dart point. The Cueva Pilote cache consists of one early stage preform, five middle stage preforms, one late stage preform, one finished Langtry dart point, and one finished Jora dart point.

The dart points show that the cache dates to the Middle Archaic period, between about 2700 to 1500 B.C., well over 2000 years earlier than the site’s radiocarbon dates. Though the cache could represent a Middle Archaic occupation of Cueva Pilote, the ceremonial nature of the rest of its artifact assemblage makes this scenario unlikely. The cache was probably found elsewhere and deposited in the cave as a votive offering late in prehistory. Recently, a quite similar cache of Middle Archaic dart points and preforms was discovered at the Lizard Hill site in southern Brewster County by archeologists from the Center for Big Bend Studies at Sul Ross State University.

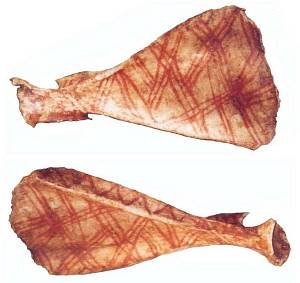

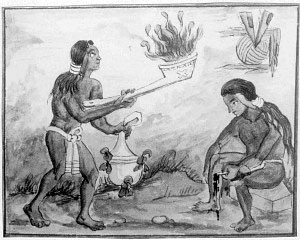

Cueva Pilote’s faunal assemblage is dominated by the remains of an adult and juvenile black bear. The remains consist mainly of long bones and ribs, but also include skull fragments, a sacrum fragment, a vertebra, a scapula, a phalanx, and a single front claw. Because of the difficulty bears would have had in entering the cave and the absence of many of the large bones, the teeth, and the other claws, it is likely that the remains were brought to the cave for ceremonial purposes. Most of the bones were found in the relic hunters' backdirt pile at the mouth of the cave, but two long bones of the adult bear were found intentionally jammed under protruding ledges or rocks on either side of the mouth of the cave.

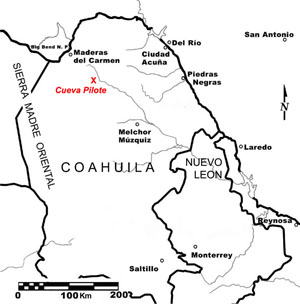

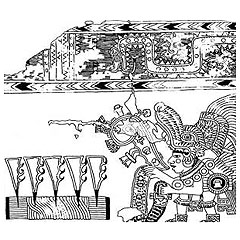

Despite its remoteness in the rugged Sierra Encantada, Cueva Pilote was not isolated from developments taking place all around it. In addition to engaging in rituals very similar to those practiced along the Rio Grande, the American Southwest, and Mesoamerica, the people who visited the site possessed many artifacts of non-local origin. Their marine shell beads came from the Gulf of Mexico, some 400 to 500 kilometers (250 to 300 miles) to the east. Their mussel shell beads came from either the Rio Grande, 100 kilometers (60 miles) to the north, or the Río Sabinas, 160 kilometers (100 miles) to the south. In addition, their gourd is a domesticated variety that was not grown in the vicinity of the site and may have been imported from the Rio Grande Valley, the Laguna District, or the Huasteca area to the east. All of this implies that they had contacts with other groups that extended well beyond the Encantadas.

Credits and Sources

This exhibit was contributed by Solveig Turpin. TBH Assistant Editor Carly Whelan created the exhibit based on the below sources and contributed additional writing. Heather Smith did the web development. Turpin also took the photographs.

Turpin holds a doctorate in Anthropology from the University of Texas at Austin where she worked as an archeologist until retirement in 1998. Her research has focused on rock art and hunter-gatherer adaptations to the arid lands of the Lower Pecos region and northern Coahuila and Chihuahua.

Print Sources

Avelerya, Luis, M. Maldonado-Kordell, and Pablo Martinez del Rio

1956 Cueva de la Candelaria. Instituo Nacional de Anthropologica e Historia, Mexico, D.F.

Eling, Herbert H., Jr. and Solveig A. Turpin

2007 Cueva Pilote: Ritual Bloodletting Among the Prehistoric Hunters and Gatherers of Northern Coahuila, Mexico. Paper presented at the 72nd Annual Meeting of the Society for American Archaeology, Austin.

Turpin, Solveig A. and Herbert H. Eling, Jr.

1999 Cueva Pilote: Ritual Bloodletting Among the Prehistoric Hunters and Gatherers of Northern Coahuila, Mexico. Institute of Latin American Studies, The University of Texas at Austin, and Instituto Nacional de Anthropología e Historia, Saltillo, Coahuila.

[English and Spanish versions of this study can be downloaded as a PDF through Research Gate and Academia] |

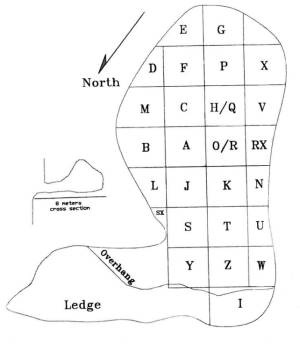

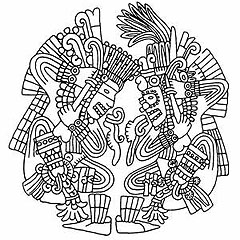

When the nine bifaces that make up the cache are superimposed on top of one another, it becomes easy to see that they illustrate a lithic reduction sequence from early stage preform to finished dart point. Graphic by Lee Bement. |

This claw from an adult black bear is the only claw recovered from Cueva Pilote. Although other bones from an adult and a juvenile bear were found, the absence of teeth, other claws, and most of the larger bones suggests that the remains were brought to the cave for ceremonial purposes.  |

These land snail shells were purposefully brought to Cueva Pilote by the people who conducted ceremonies within the cave. Spirals are commonly found in the rock art of Coahuila, and the snails’ accentuated spiral morphology may have given them ritual significance.  |

Solveig Turpin with Alvin Ivey (left) and Tom Barksdale, two of the "Hombres de la Frontera" who provided logistical assistance for her fieldwork in Coahuila. |

|