Big Lake Bison Kill

Sometime around 7000 B.C., hunters drove at least 10 bison into the mucky waters of Big Lake in southeastern Reagan County on the far western Edwards Plateau. The bison became mired in the bottom of the shallow playa lake and were dispatched by the ancient hunters. The hunters appear to have taken the best cuts of meat away to their nearby camp on higher ground. A prolonged dry period in the millennia following the bison kill caused the lake to dry up and wind blown dunes formed on the north side of the lake, covering up the bison bones.

Big Lake is an intermittent saline lake or playa, the largest in the Plateaus and Canyonlands region. Today Big Lake is a dry depression most of the time; during the 20th century it has held substantive amounts of water on average about once every 20 years following heavy rains. Before 9,000 years ago, Big Lake held water more consistently and formed a large shallow body of water that attracted animals and humans. After that time, the lake dried up and a massive sand dune formed on the north side of the lake. The massive dune formed over a lengthy period during which consistently strong southerly winds scoured the dessicated lake bed and redeposited the fine sediments. This pattern is consistent with the postulated mid-Holocene climatic interval of extreme aridity often called the Altithermal.

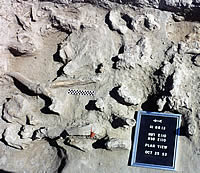

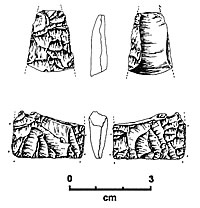

Archeologists from the Texas Archeological Research Laboratory began systematically surveying the area around Big Lake in 1988 in advance of the construction of a crude oil pipeline. They discovered the Big Lake Bison Kill site (41RG13) when they noticed a few large mammal teeth, chert (flint) flakes and a dart point lying on the ground surface. It was assumed that these materials had been unearthed during construction of a gas pipeline some years earlier. An exploratory backhoe trench was dug to evaluate the deposits.

The trench encountered a bison bone bed, which yielded a single radiocarbon date of about 6,400 B.C. Hand excavations were carried out to sample the bone bed during several short field seasons in 1989-1993 under the direction of Solveig A. Turpin. Archeologists from the University of Texas at Austin were assisted by volunteers from the Concho Valley and Iraan archeological societies. This work yielded two additional radiocarbon dates ranging from about 7100-7400 B.C.

None of the three dates from the Big Lake Bison Kill site were run on ideal materials (such as wood charcoal), hence the precise dating of the kill event remains uncertain. Nonetheless, the available dates and a fragmented Late Paleoindian dart point found in the bone bed suggest that the bison hunting event occurred at the transition between the end of the Paleoindian period and the beginning of the Archaic period, about 9,000-10,000 years ago .

The Big Lake bison remains have the potential to tell us a great deal about hunting behavior in this transitional period. Many Paleoindian hunting sites in the Southern Plains and American Southwest have been found near playa lakes. It has been postulated that hunters intentionally drove their prey into these lakes in order to bog them down and kill them. While this theory is generally accepted, there has been little direct evidence to back it up. At Big Lake, bison leg bones were discovered standing vertically in the archeological deposits providing proof that the animals were mired in the lake bottom when they were killed. Given that no butchering tools were found at the site, researchers believe that hunters carved off the choice bison parts (tongue, horns, hind quarters, etc.) and took these back to their camp for further processing.

Analysis of the bison bones revealed that there were at least 10 individual animals represented in the bone bed, including three adult females, five juveniles and two calves approximately five months old. Since historic accounts of bison show that most calves are born in April, the Big Lake bison kill probably took place in late summer or early fall.

In terms of both geography and time, the Big Lake Bison Kill site helps to fill a gap in the archeological record of Texas. The site is situated between the well known bison kills at Lubbock Lake and Bonfire Shelter and is dated to a transitional time between the end of the Paleoindian period and the beginning of the Archaic.

References

Turpin, Solveig A.

1994 Reconnaissance of Big Lake Draw: Implications for Prehistoric

Playa Utilization, Reagan County, Texas. Texas Archeological Research

Laboratory, Technical Series 40, University of Texas at Austin.

Turpin, Solveig A., Leland C. Bement, and Herbert H. Eling, Jr.

1997

Stuck in the Muck: The Big Lake Bison Kill Site (41RG13), West Texas.

In Southern Plains Bison Procurement and Utilization from Paleoindian

to Historic, edited by Leland C. Bement and Kent J. Buehler, pp. 119-133.

Memoir 29, Plains Anthropologist 42(159).