On this page:

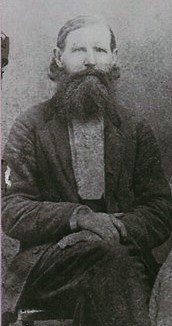

In 1830, 38-year-old John William Smith (1792-1845) and 15-year-old María Jesusa Curbelo-Delgado (1813-1894) were married in San Antonio de Béxar, modern day San Antonio. María descended from the town’s founding Spanish families, who emigrated to the area from the Canary Islands in 1731. At the time of their marriage, María’s family had lived in San Antonio for six generations, almost 100 years. Their union cemented John William Smith’s place in San Antonio society.

While John William Smith’s accolades (Texian messenger during the Siege of the Alamo, first mayor of San Antonio following Texas Independence, county tax assessor and treasurer, among others) are well-documented in military and political histories about the Republic of Texas period, María Jesusa Curbelo-Delgado’s story was a casualty of historical bias. When the archeology of the Curbelo Smith home was completed in 2022, her story was finally unearthed.

This exhibit explores both the actual foundations to their home in San Antonio and the figurative foundations to the Smith family as a political powerhouse. The history of the Smith residence and María’s struggle to maintain it after John’s death is pieced together from archival sources. Our knowledge of their household is informed by archeological investigations by Pape-Dawson Engineers. A related lesson plan gives 7th grade history and language arts students an opportunity to compare the travel experience of eighteenth-century Canary Islanders’ immigration to San Antonio with the modern experience of travelling between these distant places.

Political Context

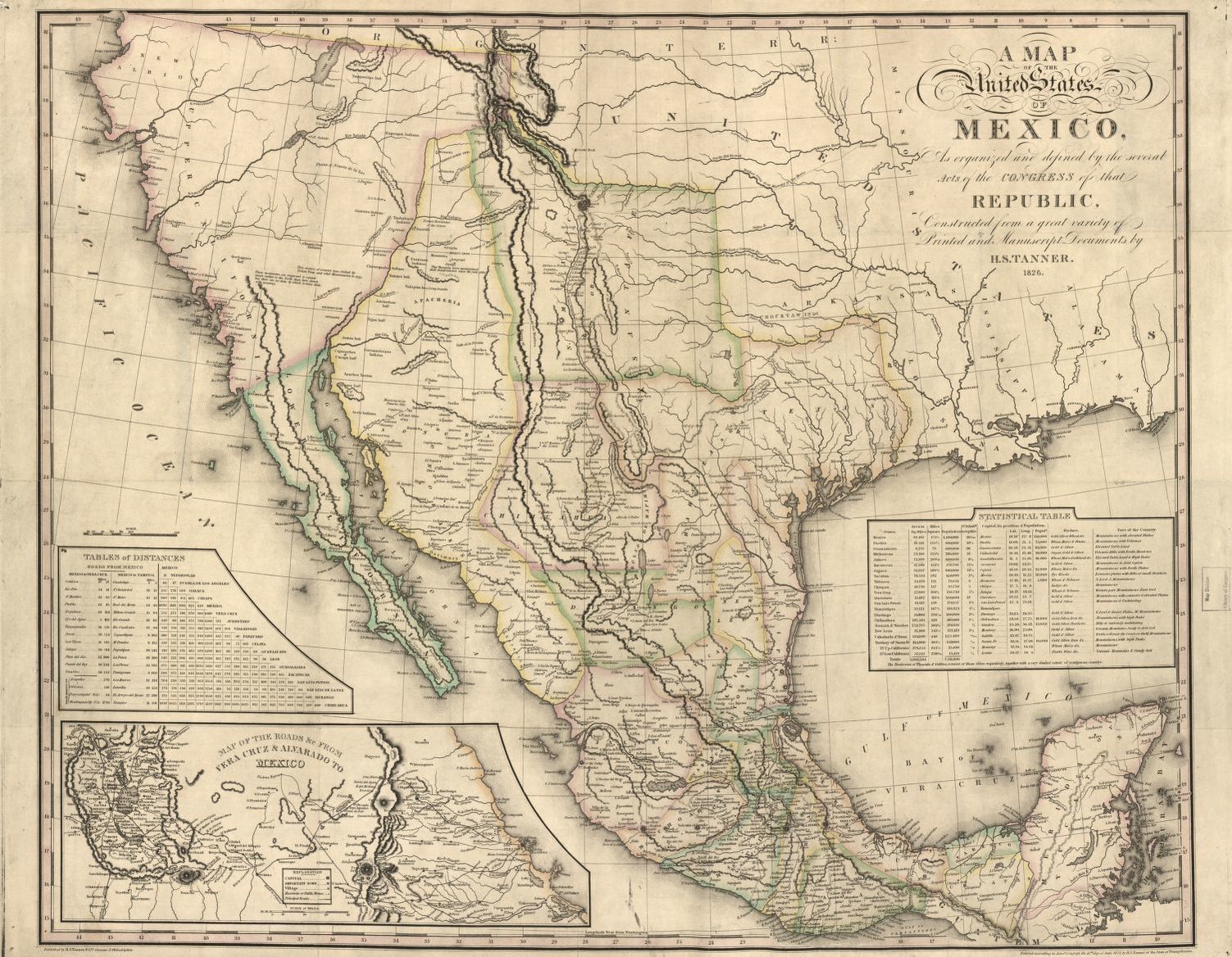

During the Mexican Texas period (1821-1836), after Mexico gained independence from Spain, Anglo immigration to Texas from the United States was a mutually beneficial solution to a variety of problems. The Mexican War of Independence left the remote settlement of San Antonio with little defense from Comanche raids, and so the new Mexican government established a colonization program that encouraged immigration of Catholic Mexican and Irish settlers to Texas, to increase the population and stimulate the economy.

Meanwhile, the popular phrase, “Gone to Texas,” was often found posted on the doors of abandoned homes across the Southern United States as Anglo debtors and others seeking a fresh start, prosperity, or adventure moved to Texas in hopes of a better life. Land was cheap and opportunities seemed endless. Between 1820 and 1827, roughly 1,800 United States citizens immigrated to Texas, many of them single men.

Among these men was Virginia-born John William Smith who left a life in Missouri to follow empresario (land agent) Green DeWitt to Texas in 1826. Having abandoned family, business connections, and community ties in the United States, John, like many other men in his position, acquired quick financial and social standing in his new home country by marrying into an established family.

Canary Islanders and the Curbelo-Delgado Family

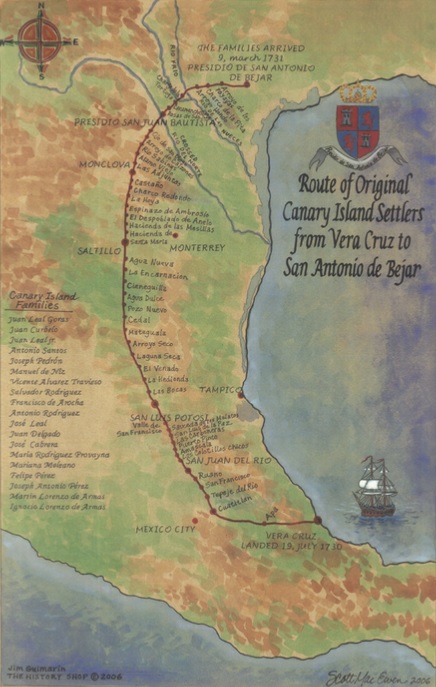

In the early nineteenth-century, when John immigrated to San Antonio, the town was governed by descendants of people from the Canary Islands, a Spanish territory off the coast of northwestern Africa. The original 56 Canary Islander immigrants, or Isleños, were brought to found Villa de San Fernando de Béjar near the San Antonio de Béxar Presidio in 1731. To incentivize these loyal Spanish subjects to relocate to Texas they were granted status as low-ranking nobles, called hidalgos. For the approximately 90 years before Mexican Independence, Isleños dominated public office in Béxar.

María was descended from Canary Island immigrant Juan Curbelo on her paternal side. Juan Curbelo was appointed Second Councilman (regidor) in 1735. His son, Joseph (alternately, José de Dios), continued the family’s ranching operation and was elected alcalde (mayor) of San Fernando de Béxar several times. María's great-grandfather was army lieutenant and lieutenant governor of the Spanish province, and her grandfather was an Indian agent to the Comanches, Tahuayazes, and Tahuacanos. María’s father, José Antonio Saturnino Curbelo, fled Texas following the Battle of Medina (1813) and re-married in Louisiana.

María was raised by her mother, Josefa Delgado, and maternal grandparents Clemente Delgado and Gertrudes Saucedo. The Delgados were also prominent San Antonio citizens descended from Canary Islanders. Clemente’s family owned one of the largest ranches in the region, and like his father and grandfather, Clemente was a regidor on the town council.

The Politics of Marriage

United States property laws at the time of María and John’s union prohibited women from owning land. In Texas, however, Spanish and later Mexican law allowed women to solely own, inherit, administer, buy, and sell property. Women often inherited equal shares of family property as their brothers and were granted equal ownership of any property acquired during marriage. The Mexican Colonization Law of 1823 incentivized marriage between Catholic immigrant men and Tejanas (Texas-born women of Mexican descent). While unmarried immigrant men received one-third league (1,476 acres) of land in Texas, those who married a Tejana were promised an additional one-fourth league (1,107 acres).

After the end of Texas Revolution in 1836, Mexican families were increasingly regarded as “enemies” of the Republic, and Anglo men increasingly held prestigious roles in government. Elite Tejanas retained their status through land ownership and marriage or kinship to military officers, government officials, and extensive landowners. Intermarriage afforded Anglo men access to contacts in the Béxar elite that merely converting to Catholicism (which they also did) could not. While Anglos came to dominate San Antonio politics after 1836, the power of the Mexican vote remained strong. Anglo men with family ties in the Mexican community consistently won local elections throughout the 1840s and 1850s.

In 1837, seven years after his marriage to María, John campaigned for the position of San Antonio’s first mayor subsequent to Independence and won. His success was reportedly due in large part to the influence of Jesusa's familial ties. Shortly after his win, the Smith family and the three people they enslaved relocated to a property that fronted San Pedro Creek and Flores Street in the Barrio del Norte of San Antonio. The family lived there for five years before John died while attending Congress at Washington-on-the-Brazos. Though illiterate, María soon began to navigate the complex administration of his estate.

María’s Fight for the Smith Estate

At the time of John’s death, the Smith estate included more than 75,000 acres of patented, deeded, and surveyed land, land certificates, and title bonds. María petitioned the court to allow her to sell various tracts of land from Smith’s estate in order to cover the expenses of her household, such as the education of her children and payment of taxes, and to defend the estate against a number of lawsuits. Some lawsuits would last for decades as supposed heirs and property purchasers filed claims against María individually and as administratrix of her deceased husband’s estate.

Shortly after his death, Smith’s past reappeared in the form of his oldest son, Samuel Smith, by his first wife in Missouri. Samuel had moved to Texas with his mother and stepfather in 1839. In 1845, Samuel filed a petition with the court opposing María’s application to administer his father’s estate and also filed a suit maintaining that he and his two sisters were the only legitimate children of John, and that his father was still legally married to his mother at the time of his marriage to María. His opposition set the grounds for a multi-decade battle as María fought for the assets of the estate. Two years later, María prevailed against Samuel in the administrative suit, and the court issued letters of administration to her. In July 1847, the court set aside property to her as her separate estate, including their 14-acre homestead, household and kitchen furniture, books pertaining to Smith’s profession, “farming utensils,” five cows, a yoke of oxen, $850 (considered to be the value of a year’s provisions for her family), and 20 hogs. The suit pertaining to the legitimacy of Samuel and his siblings as an heir was eventually heard in the Texas Supreme Court, where it resulted a decade later in the fractional awarding of interests in the Smith estate to the surviving children and grandchildren from Smith’s first marriage.

There were few avenues for women to provide for their families (outside of farming) when their husbands died, so widows often quickly remarried, as María did in April 1848 to James B. Lee, a 35-year-old native of Indiana and justice of the peace. It is likely that the Smith-Lee family lived on the John and María Smith homestead for several years. María continued to navigate the legal fallout of her husband’s death, manage the Smith estate including buying and selling land, rent houses, and raise four children aged four to eleven.

Witnesses alleged that the Lees moved from the 14-acre Smith homestead by December 1851 or January 1852. At about the same time, they sold or mortgaged the homestead to Dr. William Gilliam Kingsbury. Years of legal battles ensued and the Lees refused to acknowledge Kingsbury’s ownership. In October 1852, the Lees filed suit against Kingsbury, alleging that they had intended only to mortgage the property on Flores Street to secure a loan for $500 plus interest. A contentious lawsuit between the Lees and Kingsbury continued until 1854, when the Texas Supreme Court favored Kingsbury. The Bexar County sheriff gave him full possession of the 14-acre homestead in February 1855.

The Smith and Lee family continued to fight for the homestead. The Smith children filed a suit which was settled in 1859, when Kingsbury agreed to pay them cash, deed them a town lot, and covered some court costs. They, in turn, agreed to give up all their claims to the homestead. In 1871, María and her children and grandchildren again filed suit against W.G. Kingsbury to reclaim the property. Suits and countersuits persisted until April 1879, when María appeared before the court and stated that she would not prosecute the case any further.

Though unsuccessful in reclaiming the Smith homesite in the 1870s, María retained other property, including more than 1,800 acres. J.B. Lee died on November 18, 1886, and within two days, María took steps to divest herself of her remaining lands. She lived another eight years before dying on March 3, 1894. Her life spanned almost eight decades of history and change in San Antonio as it grew from a Spanish colony to part of the Republics of Mexico and Texas, the United States, the Confederacy, and part of the United States once again.

Archeology of the Smith House

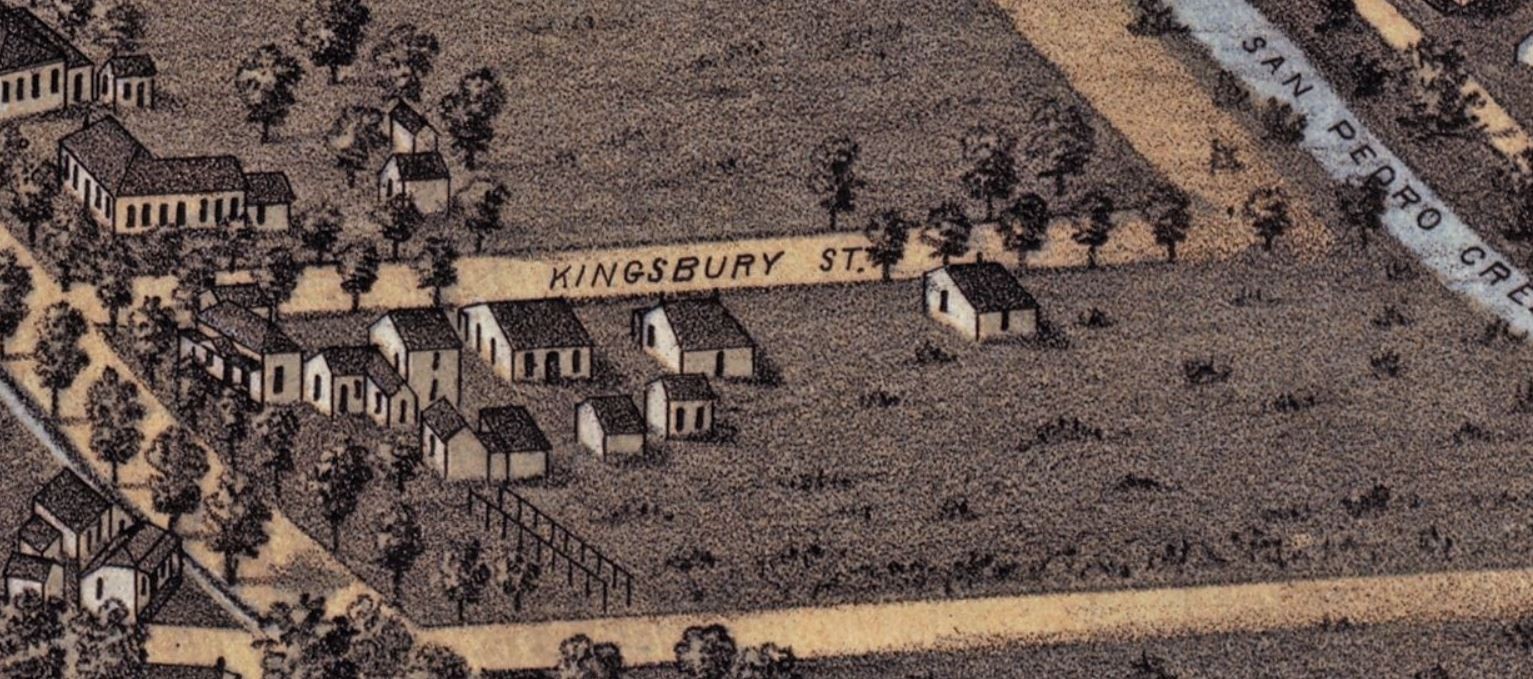

The Smith house was built before 1840. Its address was variously reported as 113 and 117 Kingsbury Street, in the Barrio del Norte. According to property records, the one-story home included “five rooms of hard rock, plastered front and back outside” that measured 36 feet wide at the front façade and 32 feet deep. The two front rooms were large, and had fireplaces with mantles, wood floors and window sash, and walls finished with plaster on wood lath. A 7-foot-wide porch extended across the front façade, which included two front entrances, each flanked by a window. A low-pitched gable roof supported by wood trusses probably was covered by a tin roof.

The 3D model below is interactive! To view a higher quality image, use the scroll bar on the right to scroll to the bottom of the 3D model and click the pyramid icon to turn on the "mesh" overlay. You can pan and zoom within the model with your device's touch pad, or by using the embedded zoom buttons.

The Smith house remained in the public memory in the first half of the twentieth century. With time, the history of the building was forgotten. The house was demolished by the early 1980s and the Fox Tech High School football field and track complex were built where it once stood.

When a new central administration building was slated for construction on the athletic fields in 2019, archeologists looked at old maps of San Antonio to evaluate the potential for a historic site in the project footprint. Sanborn maps, detailed old fire insurance maps, suggested to the archeologists that structures did indeed once stand where the building was proposed, and therefore that the archeology of the structures might be present.

After confirming the presence of intact archeological deposits through investigative trenching, Pape-Dawson Engineers archeologists mechanically scraped the project area to look for additional features. Ultimately, the shallowly buried remnants of the Smith house, Kingsbury House, and three additional residences (designated the 119 Kingsbury, P-House, and Two-Story House) were uncovered, together designated archeological site number 41BX2393.

Archeologists found four segments of the Smith house perimeter foundation, as well as an interior support wall and foundation to the former wood-frame porch. The house foundation measured about 36 feet long by 32 feet wide, consistent with archival descriptions of the house. Archival documents suggested the home contained five rooms, at least two fireplaces, and an addition (presumably to accommodate a bathroom or kitchen) but only a portion of a single interior wall was identified. The walls ranged from 2 to 2.3 feet thick and contained up to three courses of limestone blocks standing 2 feet tall, mortared together with sand and limestone paste. Archeologists also found a stone-lined well or privy (outhouse) immediately northwest of the Smith house, at its rear. It contained an abundance of artifacts likely discarded after the feature was no longer in use beginning in the early-twentieth century.

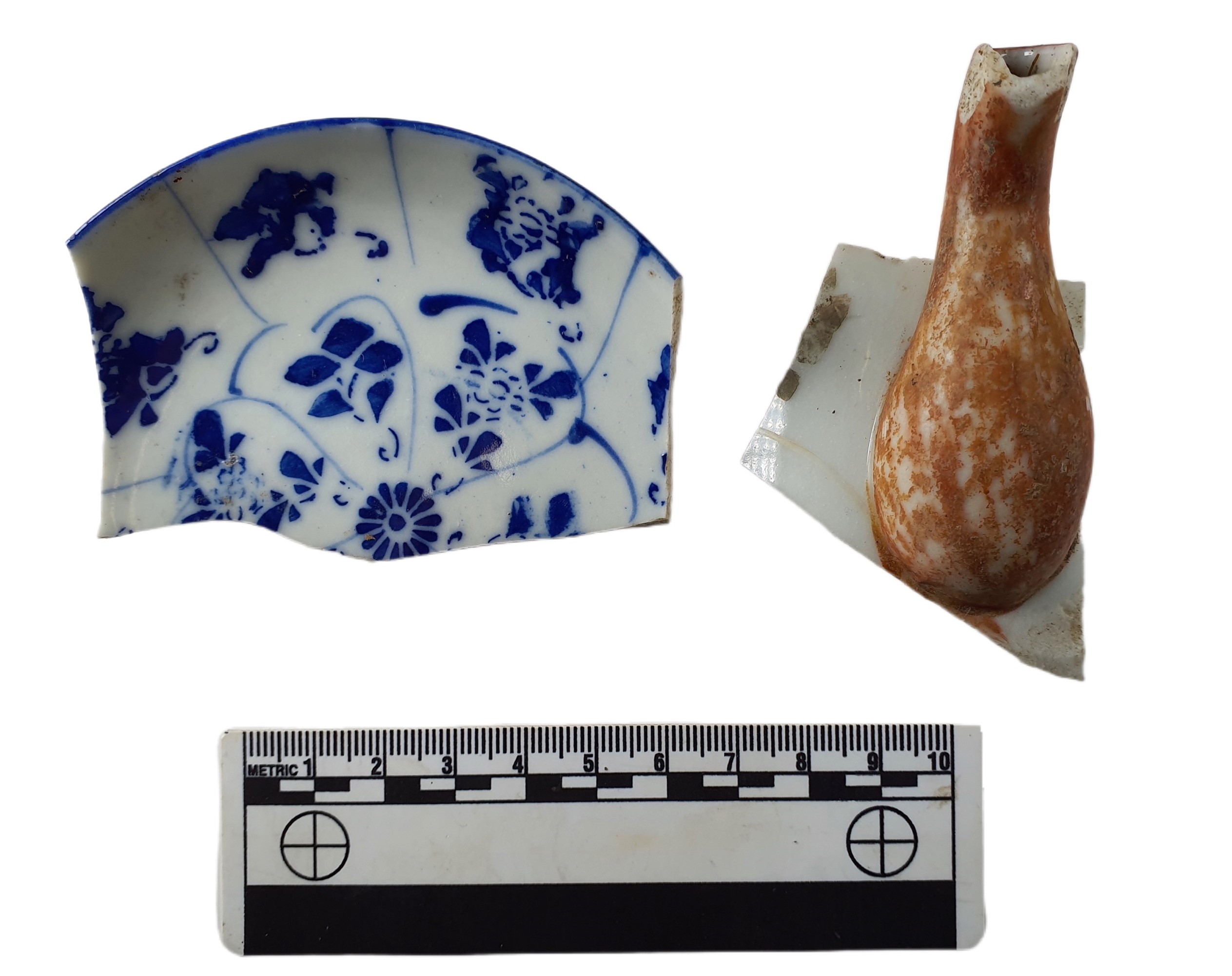

Artifacts recovered from the Smith house were, by and large, produced between 1840 and 1870, overlapping with the time María occupied the property (ca. 1840-1852). These included objects of household consumption, such as glass bottles and tobacco pipe fragments, dining utensils and ceramics, personal items such as toys, and construction materials like nails.

Bottles for wine or champagne and liquor, medicine, toiletry including Hoyt’s German Cologne, and Whittemore shoe polish were found. The presence of commodities in glass containers at the Smith house is consistent with descriptions of social pressure urging Anglo conformity on upper-class Tejanas and their children into the 1850s. The need to assimilate would have been intense for María following the death of her Texian hero husband so that her children might avoid the social stigma of their Mexican heritage; about 200 Tejano families were driven out of San Antonio around that time.

Like glass artifacts found at the Smith house, ceramics were generally produced between 1840 and 1870. Identifiable vessels included broken cups, plates, a teapot, and crocks. Edged ware, transfer print, and undecorated refined white earthenware, semi porcelain and ironstone sherds comprised most of the assemblage. Stoneware sherds recovered exhibit Alkaline glaze and Albany slip interiors and exteriors. Porcelain was hand painted. A yellowware cup handle was also recovered. A transfer print sherd recovered from the privy or well feature contains a maker’s mark for royal semi porcelain produced by A.J. Wilkinson in England.

The absence of ceramics manufactured locally or in Mexico is notable. Anglo colonization of Texas catalyzed the mass importation of English ceramics to the region, and Anglo household social practices (like tea service) were adopted to convey social status. Just as her husband converted to Catholicism to integrate into Tejano society, María probably entertained guests with Anglo social customs.

Archeologists found two toys at the site, a “Frozen Charlotte” doll fragment and a metal wagon. Frozen Charlottes were produced between 1850 and 1920 and were relatively affordable children’s toys. Dolls were often used to promote traditional domestic ideology, relegating women to roles as caregivers. Dolls made with fragile materials encouraged young girls to play indoors, and handle their toys with the care as they would a real-life infant.

Through their archeological work at the Smith house, Pape-Dawson archeologists realized an opportunity to present the overlooked story of María Jesusa Curbelo-Delgado Smith Lee. A new Texas Historical Commission historical marker was placed on the San Antonio Independent School District campus where the house once stood to commemorate her story. Archival and archeological data allow us to glimpse María's life, and the important role that she played in Texas history. María strategically navigated the complex social and political landscape of San Antonio through Mexican, Texan, and U.S. governance to maintain her family’s political power, land holdings, and wealth. Despite several challenges to her land ownership and financial stability, María raised two generations of prominent San Antonians after the death of John William Smith. While legal records demonstrate her perseverance and adeptness as a businesswoman, cultural materials recovered from her former homesite suggest she also brokered power by ascribing to Anglo customs as needed. Without María’s familial ties, guidance, and grit, neither John William Smith nor his descendants would have ascended the social ladder of San Antonio so adeptly. She was the foundation to the political powerhouse that the family became.

Lesson Plan

Teachers! The John William and María Jesusa Curbelo-Delgado Smith House is a great introduction to teaching about the Canary Islanders history of San Antonio. In the accompanying lesson plan, students will analyze maps tracing the immigration route of Maria’s ancestors from the Canary Islands to San Antonio, Texas in the 1730s. They will then use their research to write an essay comparing and contrasting travel in the 18th century and that of today. The lesson plan was written by Carol Schlenk. View lesson plan page.

Credits & Sources

This Historic Encounter was written by Dr. Karissa Basse and Brooke Bonorden with assistance from Katie Canavan, archeologists at Pape-Dawson Consulting Engineers, Inc., and edited by Emily McCuistion. Dr. Basse served as Principal Investigator and reported on the project. Melanie Nichols led the site excavations. Pape-Dawson Consulting Engineers sponsored this exhibit.

- 2017 "Women in Antebellum Texas." In Major Problems in Texas History, pp.215-220. Second Edition. Sam W. Haynes and Cary D. Wintz (ed). Cengage Learning, Boston.

- 1991 “Bexar: Profile of a Tejano Community, 1820-1832.” In Tejano Origins in Eighteenth-Century San Antonio, 3-4, 18. Gerald E. Poyo and Gilberto M. Hinojosa (ed), The University of Texas Press, Austin.

- 2017 "Mexican Women and the Process of Cultural Assimilation." In Major Problems in Texas History, pp.220-224. Second Edition. Sam W. Haynes and Cary D. Wintz (ed). Cengage Learning, Boston.

- 2022 The John William and María Jesusa Curbelo-Delgado Smith House Site, Lot 15, New City Block 131, San Antonio, Bexar County, Texas. For Pape-Dawson Engineers, On Behalf of San Antonio Independent School District, In partial fulfillment of requirements of Texas Antiquities Permit #8776, For the San Antonio Independent School District Central Administration Building Project.

- 2019 Canary Islanders in Texas: The Story of the Founding of San Antonio. Trinity University Press, San Antonio.

- 1986 Los Mestenos. Texas A&M University Press, College Station, Texas.

- 2018 San Antonio: A Tricentennial History. Texas State Historical Association, Austin.

- 2003 Las Tejanas: 300 Years of History. University of Texas Press, Austin.

- Canary Islands Descendants Association The Canary Islands Descendants Association is a lineage society whose members trace their family history to the original 16 Canary Islands families to settle in San Antonio. On March 9th, 1731, these 56 people arrived at Presidio San Antonio de Béxar after traveling more than 5,000 miles to settle in a foreign land. They are responsible for creating the first chartered civilian community and first municipal government in Texas.