Mystery Cache from the Lower Pecos

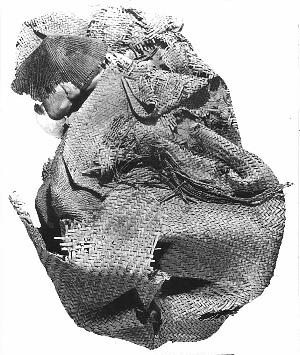

The bag from Horseshoe Ranch Cave, with its fascinating contents shown in order of their removal by analysts at the University of Texas in 1936 . Radiocarbon dated to ca. 4200 cal. B.P., during the time that the monumental Pecos River Style rock art began to flourish, the cache offers a rare--if enigmatic--glimpse into the traditions of Lower Pecos people. Reflecting both the mundane and sacred, the bag has been described as a hunter's pouch and a medicine bundle. Photo by James Neely, TARL Archives. |

|

|

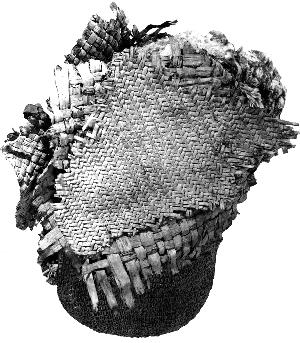

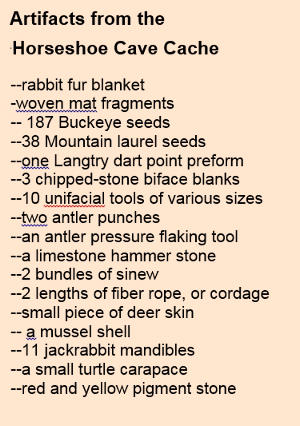

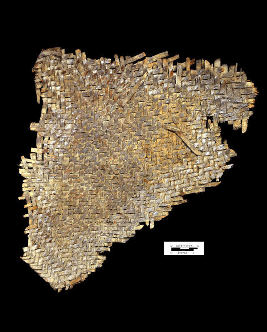

The finely woven bag, constructed of diagonally twined plant fiber, had been sewn or laced closed at the time it was placed in the cave. Although flattened from the weight of sediment covering it over the millennia, the bag originally would have been rounded, measuring about 8 inches in diameter and 10 inches in length. TARL Archives. |

|

|

|

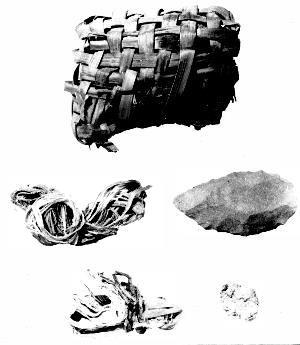

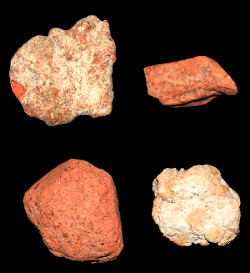

This small packet found within the larger bag contained four items: a chert biface, two bundles of animal sinew, and a nodule of paint pigment. Woven of sotol strips and sewn closed with a piece of the same leaf, this apparent special purpose kit is among the more unusual items from the cache. TARL Archives. |

|

|

|

|

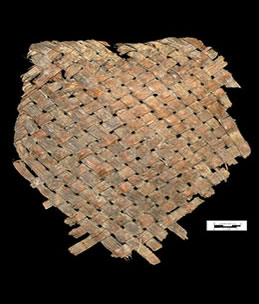

Described by excavators as a "fur bundle," this rabbit skin blanket, or robe, was found under the bag. It was made of strips of rabbit skin, with fur intact, twisted and woven amid segments of cordage made of agave lechuguilla fibers. When fully extended, it measures roughly 44 inches by 26 inches. Similar specimens have been found fairly commonly in the region. TARL Archives. |

Eleven jack rabbit mandibles were found in the bag. All but one were left sides of the jaw. Interestingly, the mandibles were described by the original analysts as "clean and unused looking." Based on ethnographic accounts, rodent teeth were used as scarifiers—tools for bloodletting or tatooing. TARL Archives. |

|

Texas mountain laurel seeds (Sophora secundi flora), or mescalbean, numbered 38. The seeds of both mountain laurel and buckeye (shown at left) contain poisonous narcotic alkaloids that can produce extreme physiological effects, including paralysis and unconsciousness. TARL Archives. Enlarge to learn more. |

|

|

|

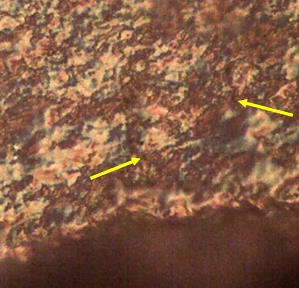

New ResearchMore recent studies of the cache at TARL are helping to unlock some of its secrets. An AMS radiocarbon assay on one of the buckeye seeds yielded a date of 4200 +/- 40 cal. B.P., an age that falls within the latter part of the Middle Archaic period known as the San Felipe interval in the Lower Pecos. Perhaps significantly, it was around this time that the distinctive Pecos River style rock art began to flourish in the region. Although the original UT investigators made no mention of rock art at Horseshoe Ranch Cave, archeologist Mark Parsons, in a 1966 area pictograph survey for the Texas Memorial Museum, noted traces of painting on the walls of the cave. The pictographs were “faint, almost to the point of invisibility”, but he made out a rendering of what appeared to be a large anthropomorphic figure possibly holding objects in both hands. Notably, the Pecos River art style incorporates monumental figures, some interpreted as shamans, and some holding pouches, atlatls and darts. According to some interpreters, the paintings are thought to be visions created under the influence of plants such as mescal, peyote, datura, or other narcotic or hallucinogenic substances. Others, such as archeologist Harry Shafer, contend that the intricacy of art work at some of the sites precludes the idea of artists being in a drug-induced state. Additional information about the bag comes from preliminary technical analyses on the stone and bone tools. The unifaces were a particularly promising group to examine using more modern techniques than were available at the time the cache was recovered. However, several specimens had patches of dark or greenish coloration on their surfaces, suggestive of organic residues, and it was determined that these should be preserved—without washing—for future analysis. TARL microwear analyst Marilyn Shoberg selected three of the other unifaces for examination. Although “rock-on-rock scratches” and other apparent post-excavation damage to the specimens presented substantial challenges, she was able to discern certain information about how the tools were used. Based on the patterns of microscarring and polish, all three had been used to cut soft animal tissue. On a large interior chert flake, for example, Shoberg noted invasive soft animal tissue polish well-developed along one edge, extending into the interior of the tool, and following the irregular topography of the crystalline surface. As shown in the accompanying photomicrograph, multidirectional single striations (denoted by arrows) are oriented at oblique angles to the edge, and were created by grit particles dragged across the surface during use.The web of overlapping striations reflects multiple cutting strokes, a pattern of wear traces consistent with moderate use cutting soft animal tissue. Interestingly, the three unifacial tools evidenced only light to moderate use, and there was no evidence of resharpening. According to Shoberg, a heavily used tool would have evidence of resharpening in the pattern of retouch flaking and variability in polish development and abrasion on "older" versus "newer" flake scars along the edge. The bone and antler specimens from the pouch were examined informally under low power microscopy by TARL archeologist Ken Brown. Of the three antler tools, two had been extensively whittled and polished. Transverse cut marks from a flint flake also were visible. Based on the use damage, the two specimens appear to have been used as pressure flakers for knapping stone tools. The third antler tool had been much less modified, although a few cut marks were present. Notable near the tip of this antler is an extensive patch of dark brown organic residue containing animal hair. Whether the tool was used during processing of the animal or was inadvertently contaminated prehistorically is open to further consideration. Like the unifacial tools, some of the bone specimens showed signs of post-excavation damage. Of the 11 jackrabbit mandibles, all but one have damage to the tip of the incisor which appears relatively fresh. It is unusual, and perhaps significant, that all but one of the specimens were left sides of the jaw. Although the mandibles were defleshed prehistorically, Brown suspects the soft tissue was removed by hand rather than with a flint tool, based on the lack of evident cut marks. Several specimens still contain patches of dried soft tissue adhering to the bone which could be suitable for AMS dating. Bloodletting and Other RitualsPart of our interest in examining the mandibles, however, was to identify possible traces of human blood residue which might suggest their use as scarifiers—instruments for bloodletting or tattooing. In the neighboring desert regions of northern Mexico, and likely throughout much of the Lower and Trans Pecos, bloodletting apparently was a part of the hunter-gatherer culture. Numerous examples of rodent mandibles, some still wrapped at the base with cording handles, have been found in the dry caves of the region. At Cueva Pilote in Coahuila, chilling evidence of this practice was uncovered, although at this site, scarification was accomplished with sharp plant spikes rather than animal teeth. Dozens of cactus spines, some still stuck in their agave pad “pincushion”, were found along with a hollow gourd, possibly for containing the blood extracted during the ritual. As site archeologists Solveig Turpin and Herb Eling note, bloodletting was an integral part of the Mesoamerican politico-religious system and can be traced through ethnographic accounts, paintings and sculpture showing this practice. Turpin describes three accounts of a fascinating ritual performed in 1607 in the vicinity of Mapimí, Coahuila to ward off the potential dire affects of a comet. "Elders punctured themselves with spines, then gathered the blood in a gourd, dipped the fresh-cut hair of a young woman in the blood, and flailed it in the air in the cardinal directions while "crying out horrifically." Another account describes a ceremony in which both men and women danced around a fire, consumed peyote, and 'drew large quantities of blood by scratching themselves with the beak of a fish.'" Other possible bloodletting devices were found at the Mitchell Ridge cemetery on the northern Texas coast. Shark teeth and an object consisting of a small oblong mass of asphaltum into which 13 sharpened hispid cotton rat incisors were set in a single row. A similar artifact was described as a shaman-curer's bloodletting tool in the historic account of Jean-Baptiste Talon, a French boy captured by Karankawas at La Salle's Fort St Louis in 1687. Early Spanish explorer Cabeza de Vaca, who wandered as a captive throughout south Texas and Mexico with various Indian groups, witnessed the use of sharp animal teeth for punishing children. Archeologist and former TARL director Thomas Hester makes an interesting point regarding this oft-cited account, noting that although archeologists tend to associate scarifiers with shamans, such instruments may have had a broader use. "Though Cabeza de Vaca describes the event as one of parents punishing a crying infant, one could suspect that it is related to curing rituals. If so, such scarification appears not to have been solely the domain of a "shaman," but could be done by anyone." Regarding the mandibles from the Horseshoe Ranch Cave cache, however, damage to the incisor tips precluded any judgment about their user as scarifiers. Brown saw no apparent traces of blood pooled up in the crevices of the mandibles or in the toothrow. The large number of mescalbeans and buckeye seeds present in the bag is also unusual and provocative. According to paleoethnobotanist Phil Dering, mescalbeans contain an abundance of poisonous narcotic quinolizidine alkaloids. "The many physiological effects of mescalbean intoxication include muscle paralysis, nausea, evacuation of the bowels, seeing red, unconsciousness, and death. These alkaloids are not, however, hallucinogenic, rather, the mescalbean and its purgative effects, along with many other sensory inputs, helped the vision-seeker reach a culturally defined condition in which to receive visions. Because of its extreme physiological effects, the mountain laurel tree, or at least its seed, was likely viewed as a powerful plant worthy of trade and of decorating ritual clothing." The presence of these seeds in the bag attests to their importance in the ancient culture of the region, Dering notes. "This kit has been described as a hunter's kit or a healer's kit, and given the interwoven nature of religion and subsistence in hunter-gatherer life, it probably served as both." Other artifacts in the bag may reveal additional information as new analytical techniques become available. Of particular interest are the residues adhering to many of the stone tools. It is unfortunate that the items were collected long before archeologists knew the proper techniques for recovering such items without contaminating them. At present, however, there is little likelihood of identifying residues that could confidently be attributed to ancient use or that would not be" false positives". (For an example of what can be learned from residue analysis on artifacts from the region, see Shafer's discussion of “dirty tools” in the TBH Hinds Cave Artifacts section.) An Enduring MysteryRecovered intact and in good condition, the twined bag from Horseshoe Ranch Cave offers a rare perspective into the world of Lower Pecos people nearly 5,000 years ago. The bag's fascinating contents include utilitarian tools as well as inexplicable items that can only be associated with ritual or sacred purpose. Archeologist Harry Shafer holds that the bag belonged to a hunter, and as such, is a reflection of ancient hunting traditions. "We see a kit with all the materials necessary for making and refurbishing weapons— spare sinew, rawhide strip, deer antler pressure flaking tools, hammerstone, bifaces for future projectile points, and uniface flake knives." He notes that although it is difficult to interpret the use of the rabbit mandibles and mountain laurel seeds, "they may have been deemed essential to ward off evil or as offerings to animal spirits, or as hallucinogens and scarifiers during hunting rituals. Such items were as important to the hunter as his spear and would therefore be an essential part of the tool kit." Archeologist Solveig Turpin places more importance on the manner in which the bag was buried in the cave. Encased in protective layers of fiber matting, it was originally thought by excavators to have been a burial. Turpin uses the term “medicine bundle” to describe the pouch, in a nod to the similarities between treatment of the pouch and numerous human bundle burials found throughout the region. Bundling is the practice of wrapping the body of the deceased in mats, with accompanying grave items such as clothing and tools, to form a bundle which is tied together with cording or rope. Yet another possibility is that the bag belonged to or was associated with one of the individuals buried in Horseshoe Ranch Cave, and that it had been placed near the grave at the time of internment. Archeologists uncovered two burials and a fawnskin pouch containing the cremated remains of a child during investigations at the site; they also learned from the land owner that other human remains had been removed from the site in the past. Two radiocarbon assays were obtained from materials in one of these burials, the elaborate grave of an infant (Burial AV1). Pieces of the fiber mat covering the burial yielded a date of 3480+/-40 cal. B.P., and a fragment of a reed pipe was dated to 3530+/-30 cal. B.P. As Turpin notes, the burial of this one-year-old child "is not only the most ornate baby burial, it is the earliest example of the bundling technique, it has the earliest painted fiber artifacts, and it is the only well-dated interment from this period." (See photo at right for more information on this burial.) The Horseshoe Ranch Cave burials suggest the bundling technique may have begun during the Middle Archaic, 1000 years earlier than previously thought. Radiocarbon dates on a prickly pear pad and piece of wood from a third burial in the cave (Burial AV2) are considerably older. In fact, the dates—7470+/-50 cal. B.P. and 8010+/-50 cal. B.P.—indicate Burial AV2 is one of the earliest internments yet dated in the region. Because the grave had been badly disturbed—only a few of the skeletal elements remained—it is impossible to know in what manner the body was interred. The initial assumption that the twined bag, or mystery cache, from Horseshoe Cave may have been associated with a burial is a strong possibility. Regardless of whether it was part of a burial, however, the carefully buried cache may reflect a burgeoning cultural tradition—"bundling"—during the San Felipe interval in the Lower Pecos region. That the bag itself was "bundled" is of particular interest. Caches and burials provide a fascinating view back into time, a personal connection to events steeped in tradition and cultural significance. Modern analysis of old collections can offer new insights and help reshape our thinking about the past. For example, recent reexamination and technical analysis of the cached material from the Paleoindian grave in Horn Shelter near Waco, Texas, has led to new interpretations of this important feature. The ca. 11,000-year-old double burial of an adult male and child contained a mix of seemingly utilitarian and ritual items not unlike those in the Horseshoe Ranch Cave cache: chipped-stone bifaces, antler tools, pigment stone, and turtle shell. Archeologists at the Smithsonian Institution National Museum of Natural History now believe the apparent utilitarian items, originally thought to be knapping instruments, were more likely tools used in ritual activities, including paint processing and possible scarification. Although puzzling to us today, the contents of the Horseshoe Ranch Cave cache, and the manner in which it was purposefully secured and buried, reflect the thought processes, traditions, and beliefs of an individual or cultural group in the ancient past. The cave was the repository for several burials and likely was the scene of numerous rituals and ceremonies held as a means to connect to the spirit world. In a future TBH Spotlight feature, we hope to highlight more of the findings and new research on materials from Horseshoe Ranch Cave. Credits and SourcesThis Spotlight feature was written by TBH Editor Susan Dial, based on sources listed below and additional new information. Web development was done by Associate Editor Heather Smith. Color photos of the artifacts were taken by Laura Nightengale and used in a Power Point presentation by Harry Shafer to the Texas Archeological Society in 2009. Boyd, Carolyn E. Butler, Charles T., Jr. Hester, Thomas R. Merrill, William L. Parsons, Mark Shafer, Harry J. 1986 Ancient Texans: Rock Art and Lifeways along the Lower Pecos. Texas Monthly Press. Turpin, Solveig A. Learn MoreFor further information about the archeology, environment and cultures of the Lower Pecos region, see the following exhibits and features on TBH: Plateaus and Canyonlands exhibit set

|

|