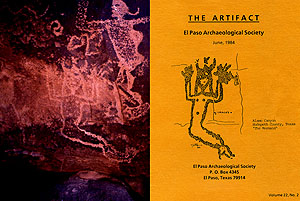

Alamo Canyon,

Rock Art District

Deep in the west Texas desert lies a boulder-strewn canyon harboring a

trove of ancient art and archeological sites. Alamo Canyon lies some 100

kilometers (60 miles) southeast of El Paso in the vicinity of Fort Hancock,

near Diablo Dam on the Rio Grande. Here, generation after generation of

native peoples came to camp, hunt, gather and cook wild plants, and tell

a bit of their story through art, symbol, and ritual expression.

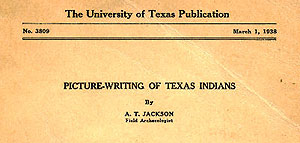

The significance of Alamo Canyon was first reported in the mid 1930s by archeologist A. T. Jackson of the University of Texas who was collecting information for a brief synopsis of rock art across Texas. In 1938, he published a wide-ranging report entitled Picture-Writing of Texas Indians which remains a highly valued resource today. Jackson reported the site as Hudspeth County Site no. 11.

Beginning in the early 1970s, the El Paso Archaeological Society (EPAS)

began a program of surveying and recording the art and archeology of the

area. In 1973 and 1974, EPAS members Kay Sutherland and Paul Steed each

led surveys of the canyon which they combined to produce a more thorough

report covering approximately 90% of the area. They also completed many

sketches of the rock art based on drawings and slides. Their illustrations

and a full report of their findings was published in a 1974 volume of The

Artifact, the journal published quarterly by the EPAS. Many of the

drawings in their report correspond to photographs of the panels previously

published by Jackson and help illuminate many details. A detailed description

of one of the most unique panels was published by Alex Apostilides in a

1984 volume of The Artifact.

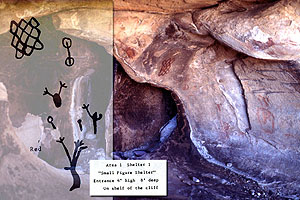

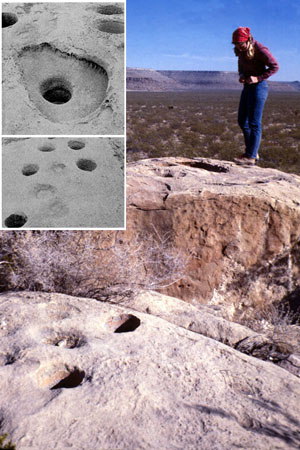

Although there has never been a formal excavation at Alamo Canyon, surveyors

have identified projectile points of the Archaic through Formative periods,

numerous bedrock mortar holes, middens, and a variety of pottery including

El Paso Brownware and Polychrome. At one location, archeologists came across

Casas Grandes Wares, a pottery originating in the cultural center of Paquime,

or Casas Grandes, hundreds of miles away in the Chihuahuan desert of northern

Mexico.

The presence of numerous burned rock middens near rockshelters along with

plant grinding features, such as bedrock mortars, suggests this area was

used repeatedly as a camp site where people gathered and roasted wild plants.

Intermittent springs provided a perennial water source. Based on the predominant

rock art of the canyon, however, it would seem that the main attraction

to the area was hunting.

Beyond the seasonal availability of resources and convenient natural shelters, the geologic formations of Alamo Canyon provide the perfect canvas for rock art. The site lies within a formation known as the Cox sandstone which formed the cliffs enclosing the canyon. Over time, this hard, rust-colored, patinated sandstone weathered into large blocks. As these blocks or boulders detached from the cliff face, they tumbled downslope and have littered the sides of Alamo Canyon. These cliffs and boulders were an ideal media for rock art, particularly petroglyphs. The brown-black patina covering the rock was pecked off during the creation of the petroglyph, revealing the buff color of the sandstone underneath. This contrast creates an unusual and aesthetically pleasing effect which is preserved in the rock art today.

Alamo Canyon contains at least 16 rock art panels—more than 500 images carved (petroglyphs) or painted (pictographs) on the rocks. Spanning some 4,000 years of cultural history, this artwork forms one of the most extensive and well-preserved rock art sites in Texas. Researchers studying these images have noted that they contain particular styles and symbols prevalent in other areas of the Southwest, pointing to relations and interaction between various contacting cultures.

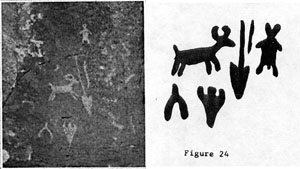

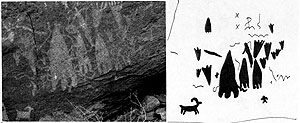

Throughout the site we find images of animal figures, or zoomorphs. Most

of these images appear to represent big-horned game such as deer and mountain

sheep. Figures of bear and desert bighorn sheep, two species that only existed

here prehistorically, also are depicted in the artwork. Interestingly, no

animal appears in isolation on these walls. Some researchers believe this

indicates that these different animals were hunted during the same time

period. According to these depictions, Alamo Canyon harbored large game

of several varieties. It is interesting to note that there are no images

of small game such as rabbits or squirrels. The absence of such smaller,

more readily available prey may indicate that food and hunting were not

the focus of the artists, but perhaps a ritual or spiritual message was

intended.

Alamo Canyon artists created images of their weapons as well, providing

archeologists with a relative dating framework for the art. Rock art has

proved difficult to date using conventional radiocarbon assays. At Alamo

Canyon, however, archeologists recognized the distinctive morphological

characteristics of the projectile points known as Shumla, a Late Archaic

stemmed dart point with deep basal notches and long, downturned tangs.

At least 124 renderings of Shumla dart points were carved into the boulders

and walls of Alamo Canyon. This point type has been identified at a variety

of sites within 100 miles of Alamo Canyon. Many of these sites contain rockart

that depicts hunting scenes in large panels that sometimes cover entire

boulders or cliff sides. At Alamo Canyon, there are several panels with

hunting scenes featuring figures of spears, men, and animals. Although many

archeologists date Shumla points to approximately 2500 B.C. to A.D. 200,

others believe they may have been in use several thousand years earlier.

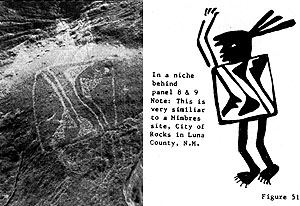

One particular figure stands out from the hunting panels. It is an image

of a horned human or what could be considered a shaman. Images of horned

humans have also been found in the Glen Canyon Area, a petroglyph site in

northern Chihuahua, and nearby Hueco Tanks. This suggests

a migration of this cultural style or transfer of it through contact and

trade relationships.

There is another artistic style found at Alamo Canyon which also suggests

the diffusion or contact of cultures. Looking east from the images of spears

and hunting parties, one sees panels or walls featuring figures of plumed

serpents, humans with pronounced leg muscles and arms in implied motion,

humans appearing to be carrying burdens, masks and faces with abstract decorations,

feathers, outlined forms, cloud terraces, and abundant geometric designs.

In one particular location named Jaguar Cave, there is an image of what

some researchers have termed a "deer Kachina Man."

All of these images are characteristic of the Mesoamerican culture of Casas

Grandes in northwestern Chihuahua, which influenced the Katchina Cult and

Pueblo Pantheon. The influence of Casas Grandes spread throughout the Mimbres

and Jornada Mogollon regions of the Southwest, and the motifs found at Alamo

Canyon may be associated with this particular cultural diffusion. Archeological

evidence of trade and contact between the peoples of Casas Grandes and Alamo

Canyon was found in Jaguar Cave in the form of Casas Grandes wares.

There is also rock art at Alamo Canyon which dates to a much later time

period. It has been associated with the Sumas, Jocomes, and Mescalero Apaches

who occupied the region at the time of their first encounters with the Spanish

in the late 1500s.

Excavations at Alamo Canyon might provide information about the people who

inhabited this area and carved the fascinating images in the rock. At present,

most of the information we have about the history of Alamo Canyon comes

from the petroglyphs themselves. Enigmatic and provacative, the rock art

offers stories waiting to be interpreted and made more meaningful.

Contributed by Heather Smith based on the reports and resources cited below.

Sources

Apostolides, Alex,

1984 Alamo Canyon: The Storyteller Woman Panel. The Artifact 22(2):11-26.

Jackson, A.T.

1938 Picture Writing of Texas Indians. UT Publication 3809, University of Texas, Austin.

Sutherland, Kay and Paul Steed

1974 The Fort Hancock Rock Art Site. The Artifact 12(4):1-64.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|