|

|

Lithic Raw Materials

Stone was an important resource for the prehistoric occupants of the Bosque River valley. Not only did the inhabitants require knappable material, such as chert, for their tools and weapons, they also used stone for their hearths and for intensive cooking of certain plant foods in oven-like features. In this section we look at toolstone and the various sources for this critical resource in the area.

Chert, or flint, was a rock used to make tools and weapons. Composed of tiny crystals of quartz, chert nodules are found in the limestone formations around Waco Lake. Once the nodules were exposed through erosion, Native Americans collected them to make tools. Rivers also moved chert nodules across the landscape, making them widely available and easy to collect at gravel bars. People used hammerstones and deer antlers to create razor-sharp edges and fashion a variety of tools from high-quality chert.

Sources of stone for the production of tools and weapons are present throughout the lower Bosque River valley, but not all of the sources provided high-quality sizable materials suitable for formal tool production. The chert-bearing lower Cretaceous Edwards Limestone is the most prominent source of knappable stone in the lower Bosque basin. Subaerial exposure of the Edwards Limestone, mapped as undivided Kiamichi Clay and Edwards Limestone, is limited to the upper reaches of the North Bosque, Hog Creek, and Middle Bosque valleys and their tributaries. Chert from the Edwards Limestone is present as a primary or bedrock source and as a secondary source in the form of fluvial and colluvial gravels.

Other minor sources of cherts and chippable stone in the lower Bosque basin consist of Tertiary lag gravel deposits on the divide between the North Bosque/Bosque and Brazos Rivers. These secondary sources were deposited by streams unrelated to and predating the modern drainage network, and often contain pebbles and small cobbles of chert, silicified wood, and other crypto-crystalline quartzes. More important, however, these lag gravels also contain quartzites used for hammerstones and grinding implements.

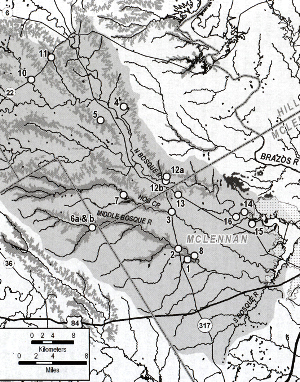

A survey of Edwards Limestone outcrops and stream channel gravel bars throughout the lower Bosque basin was conducted to examine the distribution of cherts and to identify the source(s) of the materials that occur within the archeological assemblages. Eighteen localities, some containing both Edwards Limestone outcrops and stream channel gravel bars, were examined across the basin (see map at right and Key to sources).This survey indicated that sources of chert, whether primary or secondary, are not ubiquitous across the landscape or present wherever Edwards Limestone crops out. Cherts are present at only 3 of 12 localities containing outcrops of Edwards Limestone and 7 of 12 gravel bar localities. The amount and size of chert clasts vary among the gravel bar localities depending on their proximity to primary sources of Edwards chert. At Locality 6b, a gravel bar in the Middle Bosque River, chert clasts are numerous and of suitable size for formal tool production; Locality 6b is adjacent to Locality 6a, a valley wall exposure of chert-bearing Edwards Limestone. Downstream from Locality 6b at Localities 2 and 8 (gravel bars), cherts are less numerous and on average slightly smaller. Nearby outcrops of Edwards Limestone were examined but contain no chert. This suggests that the cherts do not survive, at least in sizes useful for formal tool production, as bedload clasts over long distances.

A similar circumstance is evidenced in the North Bosque River. Gravel bar localities, such as Localities 14 and 16 on the lower North Bosque River, contained no chert or at least no chert clasts suitable for formal tool production. These localities are 15 to 18 km downstream from the closest known outcrop of chert-bearing Edwards Limestone (Locality 12a). The lack of or low bedload amounts of chert in the lower North Bosque River is not a recent phenomena, as chert clasts are also absent from a late Pleistocene fluvial gravel deposit (Locality 15) ca. 18 m above the channel just south of the McMillan site.

The cherts at the various localities throughout the basin are remarkably similar macroscopically (various shades of gray) and fairly distinct (Figure 9.4). The shades are light olive gray (5Y 6/1), medium gray (N5), medium dark gray (N4), dark gray (N3), and grayish black (N2). All contain tiny microfossils that are white (N9), bluish white (5B 9/1), and light bluish gray (5B 7/1). There is also a banded variety of chert exhibiting light olive gray (5Y 5/2), olive gray (5Y 4/1), and dark gray (N3) bands. It also contains the same tiny white, bluish white, and light bluish gray microfossils. Donald Henry, Foster Kirby and Ann Justen note six varieties of chert in the archeological assemblages from sites they investigated in the Hog Creek valley, three of which, based on their verbal descriptions, are very similar to the cherts found at our survey localities.They also note some lighter colored (white to cream-colored) cherts in the assemblages they examined that clearly do not match those cherts found at our survey localities. These materials either represent cherts from outside the lower Bosque basin or sources within the basin not yet identified.

Most of the projectile points from the Britton, McMillan, and Higginbotham sites are made of cherts that are unambiguously similar to those cherts found at the survey localities. At the Higginbotham site, 85 percent (n = 52) of the dart points are made from lower Bosque basin cherts. At the Britton site, 72 percent (n = 28) of the darts points are made from lower Bosque basin cherts, while at the McMillan site, 60 percent (n = 73) are. Of the three sites, McMillan is farthest away from the known sources of chert in the lower Bosque basin, which may account for the lower percentage of projectile points made from basin cherts. The site is also close to the apex of the lower basin, a possible entry point into the area via the riparian corridor of the Bosque River and thus more likely to yield artifacts made of materials from outside the basin.

The greater use of lower Bosque basin cherts is prevalent among all projectile point types that occur in adequate sample sizes. Analysis Unit 1 at the Britton site displays a noticeable difference in the raw materials used for the manufacture of Ensor and Godley points. Eight of the 10 Ensor points are made of the very dark gray to black variety of lower Bosque basin chert, whereas 6 of the 11 Godley points are made of the lighter variety (light gray) of local chert. The remaining 2 Ensor and 5 Godley points appear to be made of cherts from sources outside the lower Bosque basin. The striking difference between the local materials used to produce these two point styles lends credence to the idea that the point styles represent different groups. The use of different colored cherts may be an effort to portray a distinct social identity by the manufacturers (and their group) and is unlikely to be an issue of resource access, since many of the chert survey localities contain a range of color variants. This signaling of differences could be along socioeconomic or even ethnic lines. This difference, however, is not noticeable or detectable among these two point styles at other sites.

Aside from the small number of small chert clasts at Localities 14 and 16, the closest known sources of sizable chert clasts and nodules to the Britton, McMillan, and Higginbotham sites are Localities 2, 8, 12a, and 12b, which range from ca. 11.5 to 20.0 km away. It is often assumed that lithic procurement is embedded in or part of the daily practice of foraging. Given the distances between the four sites and the known sources of sizable cherts, the groups occupying these sites likely employed a foraging radius of equal distance using a foraging area of approximately 415 to 1,256 km2. However, even the low end of this estimate seems too large, particularly in light of Lewis Binford’s 2001 study in which he suggests an estimated foraging radius of 8.5 km for hunters and gatherers. This suggests one of two things: either there is an unknown source of sizable materials closer to the sites than 11.5 km, or lithic procurement, at least procurement of large clasts and nodules for formal tool production, did not take place during daily foraging in the lower North Bosque River valley. Although cores that clearly match the cherts at the survey localities are present at the sites, they are few in number. A greater amount of evidence suggests that lithic procurement—outside of the procurement of small cherts from local gravel bars—did not take place. This evidence is in the form of predominately decorticate debitage (chips lacking outer layer, or rind) and heavily resharpened dart points and other bifacial tools, many of which are near or at the end of their use lives. The tools suggest that raw materials were at a premium, and because of this, tools were heavily curated.

|

Map showing Edwards Limestone and other sources for knappable stone in the lower Bosque basin. Numbers denote sources examined during survey. Key to source areas.

|

|

|