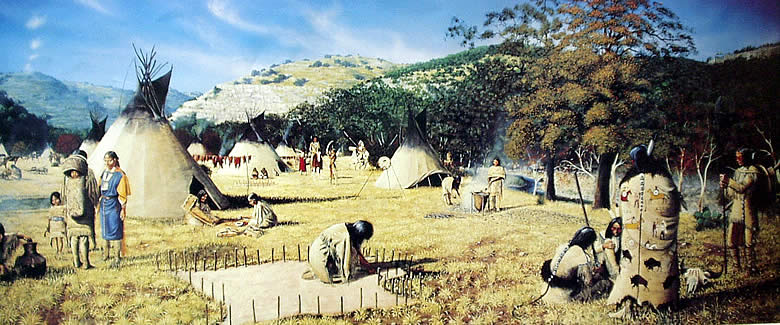

Apache Encampment in the Texas Hill Country by

George Nelson. The Lipan Apache were among several Plains tribes

pushed southward as pressure for land and resources mounted across

the western frontier. Image courtesy of the artist and the Institute

of Texan Cultures, University of Texas at San Antonio.

A bald eagle soars high above the

ground as it searches for prey. The eagle was revered

by many tribes, with the feathers a prized possession

used to adorn weapons or clothing of warriors and spiritual

leaders.

|

Approximate distribution of native

Texas tribes at the time of first contact with European

explorers in the early 1500s. Click to enlarge.

|

|

Spain applied the first destructive forces. Thousands

of the early native peoples did not survive the process

the Spanish called "reduction."

|

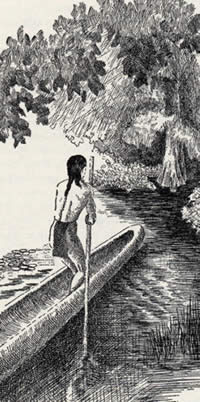

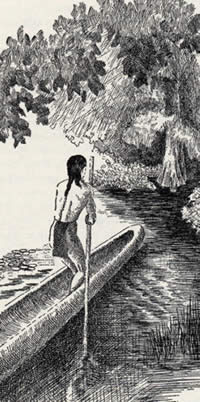

An Atakapan man skillfully maneuvers

his dugout canoe through an inland waterway. Though

few in number at the time of European contact, the Atakapans

occupied a wide swath of territory along the southeastern

Texas and Louisiana coast. While the more inland Atakapan

groups may have practiced farming like their Caddo neighbors,

the coastal groups drew heavily on marine resources.

Drawing by Hal Story (Newcomb 1961), courtesy of University

of Texas Press. Click to enlarge.

|

|

Long before the United States Army set foot

in Texas, disaster stalked the aboriginal peoples who lived

beyond the Anglo frontier. European-borne disease, intertribal

conflict, and diminishing resources had fatally weakened some

of the bands not yet obliterated. Indigenous cultures were

being crushed by forces coming from all directions.

The boundaries of modern Texas encompass vastly

different ecosystems and—on the eve of Spanish intrusion—each

region was home to different cultures. Among the major groupings

were the Caddoan cultures of the eastern forests, the Atakapan

and Karankawan people of the Gulf coast, the Coahuiltecan-speakers

of the southern Rio Grande plain, the Jumano of the middle

Rio Grande and central plateaus, and the Apachean people of

the High Plains.

Others would appear on the scene. The Tonkawa

and Wichita would migrate from the north under pressure. The

Comanche and Kiowa would push their way onto the southern

Plains a century after the early Spanish explorations. The

Cherokee and Kickapoo would come from the southeast as refugees

in the early 1800s.

The Spanish colonial efforts brought the first

destructive forces. Thousands of the early native peoples

did not survive the process the Spanish called "reduction."

Some were missionized or kidnapped into slavery in the silver

mines of central Mexico. Others were able to escape and to

be absorbed by other tribes. In the end, the Spanish reduced

these peoples more by disease than by religious conversion.

The sicknesses brought by Spanish missionaries

and French traders devastated entire villages. Outbreaks of

smallpox among the Coahuiltecans were widespread both north

and south of the Rio Grande in the winter of 1674-1675, wiped

out most of the Rio Grande mission population in 1706, and—along

with a measles epidemic—almost depopulated the San Antonio

missions in 1739. Unknown diseases were estimated to have

killed 3,000 among the Caddoan tribes in 1691, and additional

numbers in 1718. Mission Atakapans were stricken twice in

the 1750s. Karankawas suffered a "devastating scourge"

of measles and/or smallpox in 1766.

Some tribes were broken up by raiding Apaches,

who came to dominate the Plains by the end of the 1600s. The

earliest encounter between Spaniards and Apache groups had

occurred in 1541, in either the northeastern portion of modern

New Mexico or the panhandle of modern Texas. Francisco Vasqez

de Coronado gave the name "Querecho" to the people

he met there. A later exploration led by Vicente de Saldivar

Mendoza in 1599 encountered bands and villages ("rancherias")

of people that Mendoza termed "vaqueros." These

people were bison hunters, and as the Spanish had no concept

of bison other than as cattle, they characterized the woolly

animals as "vacas."

By the time the Spanish began to establish settlements

in the upper Rio Grande valley, the native puebloans had a

brisk trade going with the Plains people. The vaqueros brought

buffalo robes, meat, and tallow in exchange for cloth, pottery,

maize, and small green stones. But the Spanish tried to control

the trade, and by the mid-1600s were making captives of the

Plains Indians for use as slaves in the mines of Mexico. Thus

began a long period of hostility between the Spanish and the

Plains Apache.

The Spanish categorized the Apache of New Mexico

into western and eastern branches. The easterners included

bands that had become closely associated with the Pueblo communities

such as Pecos and Taos, as well as bands who lived farther

out on the Plains. Historians believe the Plains people included

the groupings that later became known as "Kiowa Apache

and "Lipan Apache." Both were displaced by the people

the Spanish called "Comanche."

|

Jumano Indians standing atop the

walls of their pueblo watch the arrival of Spanish explorers.

According to explorer Hernán Gallegos, who crossed

the Texas Trans-Pecos and middle Rio Grande region in

1581, the early farmers greeted them with "great

merriment." Drawing by Hal Story (Newcomb 1961),

courtesy University of Texas Press.

|

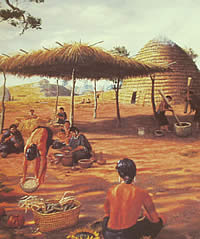

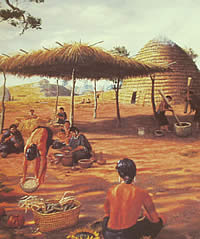

The Caddo of the East Texas forests

lived in beehive-shaped huts in expansive villages and

farming hamlets. These complex tribes were devastated

by European diseases in the 1700s before they were moved

to a Brazos River reservation and finally into Indian

Territory. Inset of painting by George Nelson, courtesy

of the Institute for Texan Cultures, the University

of Texas at San Antonio. Click to enlarge.

|

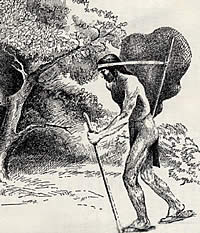

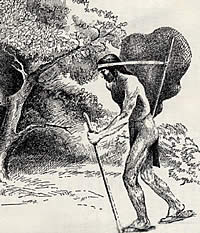

Coalhuiltecan carrying a burden.

The south Texas Indians subsisted as nomadic hunters

and gatherers in one of the harshest areas of the state

prior to being "missionized" by the Spanish.

Drawing by Hal Story (Newcomb 1961), courtesy of University

of Texas Press.

|

Buffalo on the Plains. The Spanish,

having no knowledge of the shaggy beasts, thought them

to be cattle, and called them "vacas." From

this the term, "vaquero," was derived.

|

|

|

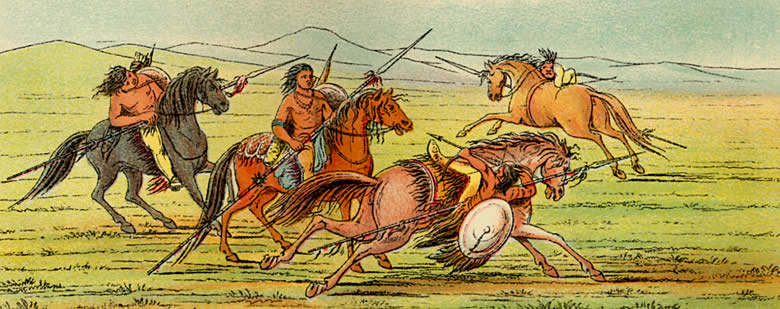

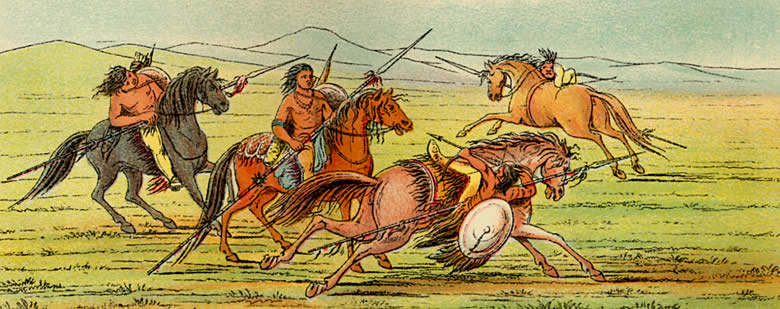

Comanche feats of horsemanship. Frontier artist

George Catlin, traveling with an expedition of U.S. Dragoons across

Indian Territory in the 1830s, visited several encampments of Comanches

and observed a variety of their activities. The Indians' skill at

horsemanship, from capturing and breaking the wild mustangs to harnessing

them toward their needs—for hunting, hauling their camp equipment,

and making war—was a source of amazement to Catlin. Read

his observations about their riding skills. |

Paths of the Comanche into Texas

during the 1700s. Adapted from Betty 2002.

|

Comanches of West Texas in war regalia.

The Comanches are a Shoshonean people who, in the 1700s,

migrated to Texas from the area that is now Colorado.

Painting by Lino Sánchez y Tapia, circa 1830s.

Courtesy of the Gilcrease Museum, Tulsa.

|

Comanche chief "Ee-shah-ko-nee"

(the bow and quiver). From Catlin 1926. Click to enlarge.

|

Wichita

grass house. Photo by Edwards S. Curtis circa 1927. |

Ruins of Presidio San Sabá,

the Spanish fort constructed to protect the nearby mission

and its Indian refugees in the Texas Hill Country. Both

the presidio and the mission efforts failed. In 1758,

a band of Comanche, Tonkawa, and Wichita sacked and

burned the mission that had provided short-lived refuge

for the Lipan Apache.

|

|

The Comanche are a Shoshonean people who migrated

from the north to the southeastern plains of modern Colorado.

The name, "Comanche," is believed to be the Spanish

derivative of a Ute word meaning "someone who wants to

fight with me all the time." The first Spanish sighting

of Comanches in New Mexico occurred in 1705. Less than 15

years passed before the newcomers began to unsettle New Mexico's

northeastern frontier with attacks against the pueblos and

Apache rancherias. The Comanche then embarked on a complicated

50-year pattern of alternately raiding the Spanish and trading

with them, but their attitude toward the Plains Apache was

unremittingly hostile.

By the mid-1700s, the Comanche had shattered

the Apache presence in eastern New Mexico. Some villagers

left the Plains and withdrew to the relative security of the

pueblos. Others retreated to the east in the face of the Comanche

onslaught. In 1724, Comanches were reported to have defeated

a force of Plains Apaches in a nine-day battle somewhere in

northwestern Texas called El Gran Sierra del Fierro.

Comanche movement onto the southern Plains was

in a generally southeastern direction throughout the 1700s.

The deeper the migration moved into Texas, the more it pressured

the Lipan, who occupied the Edwards Plateau. The Lipan adjustments

brought them into contact with the Wichita and Tonkawa in

the vicinity of the Cross Timbers to the east.

The Spanish had discovered Wichita villages

in 1541, then again during Juan de Oñate's expedition

in 1601. The explorers found many large settlements dispersed

along rivers and streams in an area encompassing the south-central

portion of modern Kansas and the north-central portion of

modern Oklahoma. These settlements began to be moved southward,

beyond the reach of raiding Osage Indians, who in the early

1700s were being supplied with guns by French traders.

Oñate's expedition also had encountered

the Tonkawa, in either the region of the modern Oklahoma panhandle

or the south-central portion of modern Kansas. There appear

to have been two groups of Tonkawa speakers by the late 1600s,

one located along and north of the Red River in modern Oklahoma

and the other along and between the Brazos and Navasota rivers

in Texas. By the mid-1700s, some Tonkawa had begun to congregate

at a large settlement, known as the "Rancheria Grande,"

on the San Gabriel River of central Texas.

The Rancheria Grande was a haven for a number

of disparate aboriginal groups driven from their homelands.

In 1748, the Spanish established a mission and presidio on

the San Gabriel to protect the Rancheria Grande refugees from

Lipan raids, but Spanish protection proved illusory, and the

mission was abandoned in 1756.

The Tonkawa then allied themselves with the

Wichita, which in turn brought them into a short-lived alliance

with the Comanche with whom the Wichita traded and shared

a hostility toward the Plains Apache. In 1758, a force of

Comanche, Tonkawa, Wichita, and representatives of other tribal

groups attacked a Spanish mission established for the Lipan

on the San Saba River.

To replace the San Saba mission, the Spanish

established two others for the Lipan in the El Canon area

of the upper Nueces River west of San Antonio. These immediately

fell prey to Comanche raiding parties. The wedge of Comanche

advance split the Lipan. Some, who became known as "upper"

Lipan, would gravitate toward the southwest, into the range

of their Mescalero Apache kinsmen. The "lower,"

or "southern," Lipan moved south and east, to the

fringes of the Edwards Plateau and beyond.

Meanwhile, Wichita groups moved from above the

Red River into the middle Brazos and upper Trinity River valleys.

The Wichitas' ever-deeper intrusion into Tonkawa territory

ended the brief period of amicable relations between the two

tribes. The Tonkawa slid southward in response, and with their

former Lipan enemies formed a new trade relationship with

southeastern tribes and the French in Louisiana.

The Comanche extended their control of the southern

Plains—soon to be called "Comancheria" by the

Spanish—onto and beyond the Edwards Plateau by the end

of the 1700s. They secured their western flank and profitable

trade relationships in 1786 by entering into a truce with

the Spanish in New Mexico. About 1800, they absorbed a threat

coming from their northeast by entering into an historic truce

with the Kiowa, another tribe of Plains raiders.

|

Comanche braves. Photo, circa 1867-1874,

courtesy of the Center for American History (#01355),

The University of Texas at Austin.

|

|

In the early 1700s, the Comanche embarked on a complicated

50-year pattern of alternately raiding the Spanish and

trading with them, but their attitude toward the Plains

Apache was unremittingly hostile.

|

Lipan Apache warrior, drawn ca. 1858

during a U.S. Mexican border survey.

|

Tonkawa beaded moccasin from Fort

Griffin area, north-central Texas. Courtesy Fort Griffin

SHS. Photo by Lester Galbreath.

|

Approximate distribution of Indian

groups in Texas, circa 1776. Click to enlarge.

|

Plains Indian woman on muleback,

circa 1850s. Artist Friedrich Richard Petri painted

a variety of people and scenes in the area of his Fredericksburg

home in the Texas Hill Country. His drawings of Indians

in the area document not only their costume and habits

but their amicable relationships with some of the settlers.

Click to see full image. Courtesy Texas Memorial Museum.

|

|

|

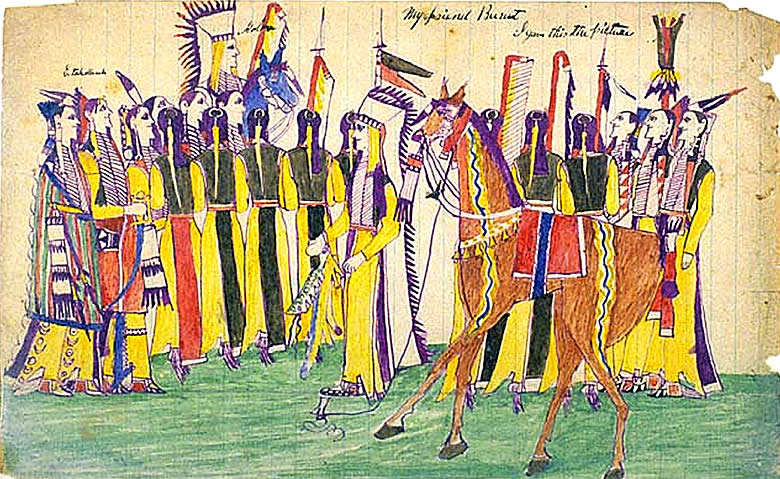

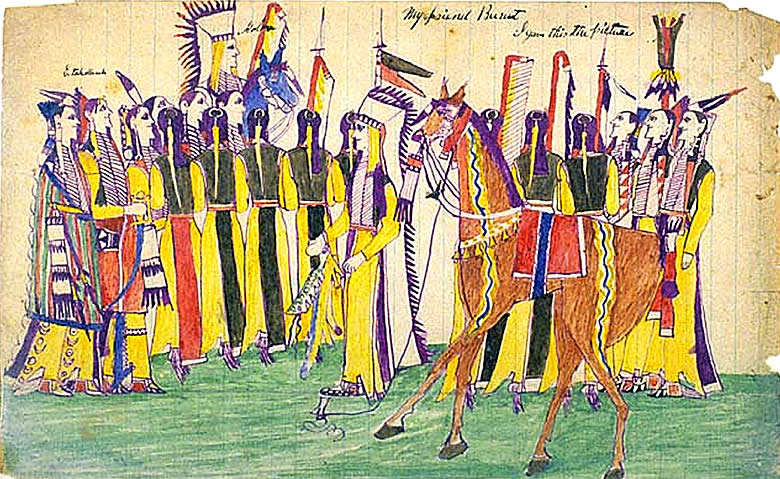

Kiowa painting of Koba (Wild Horse) wearing feathered

headdress on horseback with group of men including Etahdeleuh (Boy

Hunting), carrying lances. Watercolor, 1875, Fort Marion Prison.

Image courtesy National Anthropological Archives, Smithsonian Institution

(INV 08547626 NAA MS 39C).

|

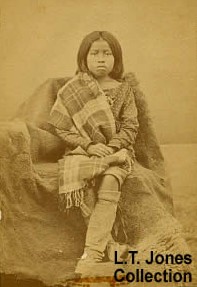

Kiowa boy, wearing bone breastplate

and striped cotton clothing. Photo circa 1867-1874,

courtesy of the Center for American History, Caldwell

Collection (#10182). Click to see full image.

|

Comanche encampment. The circa 1867-1874

photo is identified as Quah-ah-da Comanche camp, possibly

that of famed Comanche chief, Quanah Parker. Courtesy

of the Center for American History, Caldwell Collection

(00478), The University of Texas at Austin. Click to

see full image.

|

Aproximate areas of Indian groups

in Texas during the nineteenth century. Clcik to enlarge.

|

Eagle feather warrior headdress,

Plains Indian. Courtesy Panhandle Plains Historical

Museum Collection. Photo by Jeff Indeck.

|

|

|

Site of the circa 18,000-acre Comanche

Reservation established on the Clear Fork of the Brazos,

north-central Texas, in 1855. About 450 Penateka, or

southern Comanches settled there and were fairly successful

at farming, in spite of droughts. But tribal discord,

continued hunting and raiding, and inadequate protection

(from Anglo settlers) by U.S. troops, among other problems,

doomed the reservation effort, and the Comanches were

removed to Indian Territory in 1859.

|

|

The attacks by soldiers and rangers had been demoralizing,

but what made the losses critical was that they compounded

the devastation wrought by disease.

|

Invoice of property belonging to

the "several tribes" (Caddos, Wacos, and others),

at the time of their removal from the Brazos Reservation

in north Texas to the Wichita Agency, Indian Territory,

1859. Note the prevalence of farm equipment. Invoice

prepared by Robert S. Neighbors, agent. Transcript of

document from Noel 1924.

|

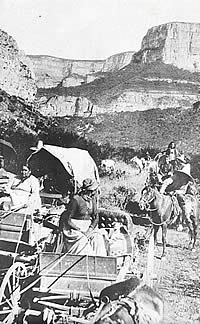

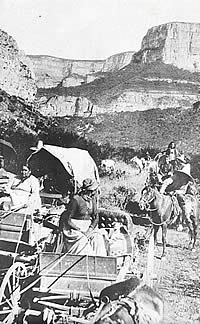

Natives migrating to Mexico in wagons.

The travelers shown are thought to be Kickapoo, ca.

1907. Courtesy National Anthropological Archives, Smithsonian

Institution (NEG 00741 A). Click to enlarge.

|

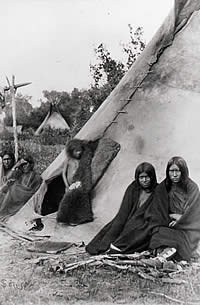

Kiowa camp, ca. 1867-1874. Photograph

courtesy of the Center for American History, Frank Caldwell

Collection (#10187), The University of Texas at Austin.

|

|

The Kiowa are believed to have migrated from

the Yellowstone River region of modern Wyoming or Montana

under easterly pressure from the Cheyenne and Sioux. They

were accompanied onto the southern Plains by the Kiowa Apache,

a group linguistically related to the Lipan of Texas and Apache

of New Mexico, but who had earlier migrated to the north and

attached themselves politically to larger and stronger tribes.

As the Kiowa moved south, they continued to

be pressed from the east—in this case by the Pawnee and

Osage—and probably encountered the Comanche near the

Arkansas River in modern Kansas. Elements of the two tribes

initially dueled over this portion of the buffalo range before

forging an alliance that would exist for more than a century.

Interactions among the diverse peoples of Spanish Texas became

increasingly skewed by forces east of the Mississippi River.

The English colonists of the mid-Atlantic seaboard had displaced

the tribes along and on either side of the Appalachian mountain

range and forced some of them into the "Northwest Territory,"

the area drained by the Ohio River and embracing much of the

modern states of Ohio, Indiana, and Illinois. This migration

had forced the Osage to abandon the Ohio valley for the prairies

of modern Kansas and Oklahoma. In the early 1800s, they were

joined there by several of the tribes that had elbowed them

out of the old Northwest Territory—Delaware, Kickapoo,

Potawatomi, and Shawnee among them—as those tribes were

again displaced by whites. Now, however, the eviction notices

were being served by the new United States of America.

Similar pressure on the southeastern tribes

caused many Cherokees to move from the southern Appalachia

hills into western Arkansas. Others followed the Alabama and

Coushatta tribes into Texas, invited along with Anglo-American

colonists during the waning days of Spanish rule.

In 1825, U.S. President James Monroe suggested

the idea of moving all of the Indians out of the eastern United

States to "vacant" lands west of the Mississippi.

The region between the Missouri River and the Red River became

envisioned in the white mind as the "Indian Territory"

that could be used to relocate all of the tribes removed from

the east. The southeastern tribes—Cherokee, Chickasaw,

Choctaw, Creek, and Seminole—joined the lately arrived,

old Northwest tribes as interlopers on the lands historically

occupied by the Wichita north of the Red River.

The fringes of the southern Plains soon became

crowded. The "removed" tribes spread out, impinged

on each other, and filtered south into Mexican Texas. Some

took up residence among the Caddo villages of the eastern

Texas pine forests. Others gravitated to the Wichita villages

farther west, such as those of the Waco and Tawakoni along

the Brazos River valley. The Lipan and Tonkawa also found

themselves with new neighbors to their south, where they encountered

the Anglo-American colonists moving up the Brazos, Colorado,

and Guadalupe River valleys from the Gulf Coast.

The Americans became successors to the raid-and-trade

relationship the Lipan and Tonkawa had conducted with the

Louisiana French. By the mid-1830s, Anglo-Texan settlers were

joining the Tonkawa in attacks on Wichita and Comanche villages.

The Anglos most likely found the Comanche at the edge of the

Cross Timbers of northern central Texas. The Tonkawa called

these Comanche "penetixka," and they probably were

of the division of Comanches that would become the best-known

to the Anglo-Texans.

The Anglos separated the Comanche divisions

into "southern," "middle," and "northern"

groupings. At least 13 major and minor tribal divisions were

known to, or remembered by, the Comanche who survived into

the late 1800s. The later Anglo accounts emphasize seven divisions.

The Penateka were the most numerous and sometimes were called

"southern Comanches" by contemporary white men.

The Nokoni, Tanima, and Tenewa would be grouped together as

the "middle" Comanche. The Kotsoteka, Quahadi, and

Yamparika would be considered "northern."

Stephen F. Austin secured relatively peaceful relationships

with the Tonkawa and Lipan while his colonists drove the Karankawa

into virtual extinction. When Texas independence was declared

in 1836, Sam Houston was dispatched to make treaties with

the Cherokee and other immigrant tribes on the northern frontier.

Houston succeeded and, although the Texas Congress would reject

many of his efforts, the Republic of Texas attempted to maintain

peace with most of the tribes throughout Houston's first term

as president.

Houston's successor, Mirabeau B. Lamar, dramatically

changed Texas Indian policy. Most of the immigrant tribes

of eastern Texas were driven out of the state—only the

Alabama and Coushatta were allowed to remain—and the

Caddo and Wichita retreated up the Brazos River. The Penateka

suffered heavy losses to disease and battles with white soldiers,

militiamen, and rangers during the early 1840s, when Lipan

and Tonkawa were enthusiastic scouts and warriors for the

Anglos in their raids on Comanche villages. By the time Houston

resumed the presidency in 1841, the Penateka had withdrawn

from the Cross Timbers and Edwards Plateau.

The Texas government returned to Houston's

earlier Indian policies during the remainder of the Republic

period. These efforts included the establishment of trading

houses at which even Comanches could exchange hides for manufactured

goods. Extensive negotiations were conducted and several treaties

were concluded. But the agreements were always one-sided:

the Indians would return any captives and stolen livestock

and would not come into white settlements except for authorized

trading. Although the Penateka demanded an identifiable boundary

to mark Comanche lands that whites could not enter, none was

ever agreed to by the government.

Annexation to the United States in 1845 brought

Texas theoretically under the protection of the U.S. Army,

which in 1848 began to build forts along the frontier of white

settlement. By the early 1850s, the U.S. government gave up

on the national policy of trying to "remove" Indians

beyond the reach of white migration, and in its place substituted

the idea of confining the Indians on reservations that whites

could simply bypass on their way west.

The U.S. government owned no land in

Texas, and had to await the state legislature's authorization

of two reservations on the Brazos River in 1854. One, the

"Brazos Reserve," was located near the Army's Fort

Belknap and housed about 2,000 remnants of the Caddoan and

Wichita groups, Tonkawa, and Delaware. The other, on the Clear

Fork of the Brazos (the "Upper Reserve"), accommodated

as many as 450 Penateka Comanche. Residents of both reservations

were instructed to take up farming. Those of the Brazos Reserve

had some success, and also furnished scouts and warrior allies

for the Army and Texas rangers.

Local white opposition forced the removal of

the reservation residents to the "Indian Territory."

There, some became pawns in the white man's Civil War, as

both Union and Confederate emissaries attempted to enlist

them in the conflict. In 1862, about half of the 300 Tonkawa

were massacred by members of other tribes, some of whom were

Union allies. The survivors sought refuge near Fort Belknap,

and a substantial number served in the Texans' frontier defense

organization for the remainder of the war.

The Civil War period brought something of a

retrenchment on the western Texas frontier. Mexico became

a refuge for migrating bands of Kickapoo, Lipan, and Seminole

who shunned the reservations in Indian Territory. Comanches

and Kiowas continued to travel their historic trails between

the High Plains and the Rio Grande. The early 1860s were comparatively

quiet along the frontier line, perhaps due to the Comanches

and Kiowas skirting the edge of white settlement. But military

patrols began to lapse as the Civil War reached its height,

the Indians became emboldened, and the whites began to abandon

the state's westernmost counties as raids increased.

But time was running out for the Plains tribes.

The Penateka had declined rapidly in the years before the

war, and the status of the "middle" Comanches was

increasingly precarious. The Tenewa had become all but extinct

as an identifiable division. Even the northern Comanche bands

had found that their villages were not beyond the reach of

the white man's raiding parties.

The attacks by soldiers and rangers had been

demoralizing, but what made the losses critical was that they

compounded the devastation wrought by disease. An 1816 smallpox

epidemic had killed an estimated 4,000 Comanche, along with

significant numbers of Kiowa and Kiowa Apache. A recurrence

of the disease in the winter of 1839-1840 killed large numbers

in each tribe. A cholera epidemic in 1849 took even greater

numbers than had been lost to smallpox. The Plains tribes

were again struck by "terrible ravages" of smallpox

in 1861.

Perhaps most ominous of all was the often erratic

availability of resources. The bison—or buffalo—had

been a staple of Plains life since prehistoric times, providing

food, clothing, shelter, and utensils. The spread of Spanish

horses from the New Mexico settlements onto the Great Plains

had changed the character of the aboriginal bison culture.

Hunters no longer had to rely on herds wandering into their

vicinity so that they could steer the animals into a trap.

Once mounted, hunters and their families became pursuers.

Mobility—the ability to follow the buffalo in any and

all seasons—became the prerequisite to prosperity. Horses

provided that mobility, but the same horse that carried a

hunter after the buffalo also carried him into contact with

competing hunters from other tribes.

|

"United States Indian Frontier

in 1840, Showing the Positions of the Tribes that have

been removed west of the Mississippi," by frontier

artist George Catlin. While not all tribes are shown,

the map reflects the relative positions of the southeastern

groups who were relocated to "vacant" lands

by order of President James Monroe in 1825. Map from

Catlin 1926.

|

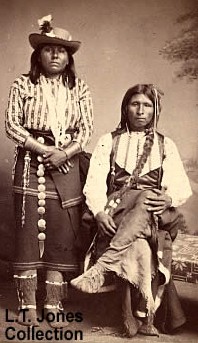

Kiowa Apache man and wife, Fort Sill, Indian Territory.

Photo courtesy of Lawrence Jones, III. View

large image.

|

Plains Indian family emerging from

woods. As Anglo settlers moved up the Brazos, Colorado,

and Guadalupe River valleys, they came into increasing

contact with Indian groups. Fredericksburg artist Freidrich

Richard Petri enjoyed an amicable relationship with

many. Painting ca. 1850s, courtesy of the Texas Memorial

Museum.

|

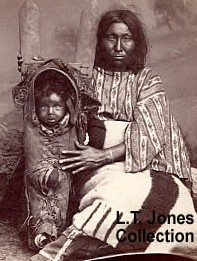

Comanche woman with child in cradleboard,

Fort Sill, Indian Territory. Photo ca. 1872-1875, courtesy

of Lawrence Jones III. View

large image. |

Plains Indian beaded leather pouch.

Courtesy Panhandle Plains Historical Museum Collection.

Photo by Jeff Indeck.

|

Kiowa brave. Tow-An-Kee, son of Lone

Wolf. Killed in Texas in 1873. Photo, ca. 1867-1874,

courtesy of the Center for American History, Caldwell

Collection (#03962), The University of Texas at Austin.

|

On reservations in Texas and later

in Indian Territory, Indians tried their hand at farming,

with moderate success. Inset of painting by Nola Davis,

modeled after Twilight of the Indian by Frederick Remington.

Courtesy of Texas Parks and Wildlife Department, Fort

Richardson SHS.

|

Kickapoo Chief, Babe Shkit, ca. 1894-1907.

National Archives.

|

Kickapoo camp and corrals, possibly

in Mexico.

|

Comanche trails across Texas into

Mexico. Adapted from Weber 1985.

|

|

Mobility—the ability to follow the buffalo

in any and all seasons—became the prerequisite

to prosperity. Horses provided that mobility, but the

same horse that carried a hunter after the buffalo also

carried him into contact with competing hunters from

other tribes.

|

|

|

Buffalo silhouetted against a Texas sunset. Photo

courtesy Texas Parks and Wildlife Department.

|

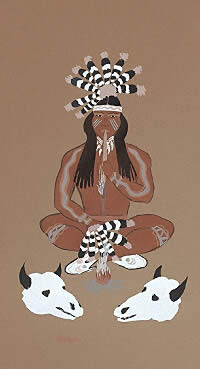

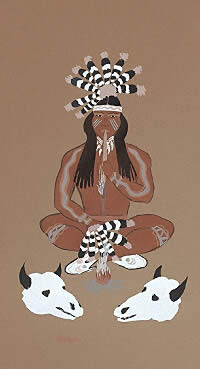

"Making Medicine." Kiowa

drawing by Mopope, reflecting importance of buffalo

to the Indian. Painting courtesy of the National Anthropological

Archives, Smithsonian Institution (#INV 090656600 NAA

MS 7536).

|

Topin Tone-oneo, daughter of Kicking

Bird. The only one of the great Kiowa chief's children

to survive him, she was with the first group of students

sent to Carlisle Indian School in 1879. Courtesy of

the Center for American History (#CN 01362), University

of Texas at Austin.

|

Plains Indian gourd rattle. The

dried gourds were filled with small pebbles that produced

a rattling noise when the object was shaken. Courtesy

Panhandle Plains Historical Museum Collection. Photo

by Jeff Indeck.

|

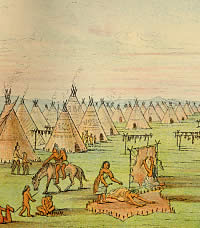

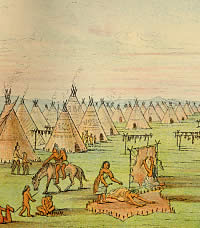

"In the Great Camanchee Village"

near the Texas panhandle, circa 1840s, by frontier artist

George Catlin. The scene, he notes, records but a small

part of the extensive village. The "wigwam of the

chief" is in foreground, and women are drying meat

and working buffalo hides nearby. From Catlin 1926.

Click to see full image.

|

|

By the early 1800s, Comanche and Kiowa, Arapaho

and southern Cheyenne, and Osage and Pawnee began bumping

into each other on the buffalo range of modern Kansas and

Oklahoma. After varying periods of conflict, truces were arranged

and reduced the bloodshed, but also circumscribed each tribe's

hunting territory. For the Comanche and Kiowa, the upshot

was that their primary range became the region south of the

Arkansas River, between the Sangre de Cristo and Sacramento

mountain ranges on the west and the Cross Timbers on the east.

This was excellent bison-hunting country, as

far as it went. Winters were relatively mild and the bison

had roamed as far south as the Rio Grande in historic times.

But the southern range was also fragile, subject to extremes

of heat and drought that scorched the grasses and dried up

the water courses. In such conditions, the bison could leave

the range altogether, as they appear to have done in the late

1780s, when for three successive years the Comanche had to

go into the New Mexico pueblos and towns to beg for corn.

Tree ring data appear to validate Kiowa calendars

that indicate long periods of diminished rainfall between

1845 and 1875. The calendars note several summers of drought

or dust during those years, and corresponding times of "little

buffalo" or "no buffalo ." Only twice after

1840 do the calendars include the observation, "many

buffalo."

Within their restricted hunting territory,

the Comanche and Kiowa also had to contend with transgressors,

the New Mexican ciboleros who ventured onto the plains to

hunt for bison. Although early Spanish expeditions had engaged

in acts of wholesale slaughter—one foray with the Jumano

Indians in 1683 killed about 8,000 animals along the Concho

River of Texas—the ciboleros appear not to have become

an important phenomenon until the 1800s. One account in the

1830s estimated that the New Mexicans were killing a minimum

of 10,000 to 12,000 bison annually. Their activities angered

the Cheyenne, who drove them off their hunting grounds in

the 1850s. This in turn brought them into confrontations with

the Comanche and Kiowa after the Civil War, when they were

reported to be having such a significant effect on the bison

herds on the Llano Estacado that Army commanders in New Mexico

considered banning their hunts.

The uncertain political status of Texas and

the other former Confederate states at war's end offered perhaps

the last best hope for the Plains tribes to maintain their

traditional way of life. In the fall of 1865, several Comanche

and Kiowa leaders entered into what became known as the Treaty

of the Little Arkansas River. Representatives of the government

of the United States pledged to set aside a huge reserve that

comprised most of the western half of modern Oklahoma, all

of the Texas panhandle, and the remainder of the Llano Estacado

east of the Texas-New Mexico border.

The Texas portion of the reserve had

been land that few white men had wanted to cross, much less

own, but it had also been state land, outside the control

of the U.S. government. Within two years the government reneged

on the treaty, obtained the signatures of Comanche and Kiowa

leaders on the new Treaty of Medicine Lodge Creek, and reduced

the reserve to only six per cent of its original size. All

that remained was a corner of the designated "Indian

Territory." The substantial portion of the bison range

that would at least in theory have been off limits to whites

was left open to the commercial slaughter that touched off

the Red River War of 1874-1875.

The last of the independent Comanche, Kiowa,

and Kiowa Apache surrendered to reservation life in 1875.

Some of the Lipan and Mescalero bands held out in northern

Mexico until the early 1880s, when Mexican and U.S. Army forces

drove them onto reservations or into extinction. The 1890

Census showed 1,598 Comanche at the Fort Sill reservation,

which they shared with 1,140 Kiowa and 326 Kiowa Apache. The

Fort Stanton reservation in New Mexico had 473 Mescalero and

40 Lipan. Few individuals from the once-great forest and prairie

village groups had survived in Indian Territory, 536 of the

East Texas Caddo and 358 of the Wichita.

|

Plains Indian fleshing tool with

serrated metal edge, used for butchering large game.

Courtesy Panhandle Plains Historical Museum Collection.

Photo by Jeff Indeck.

|

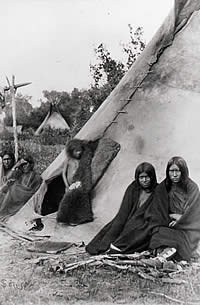

Four Apache Indians huddle in foreground

of what is identified as an Arapoho hunting camp, ca.

1867-1874. Note meat hanging over drying racks. During

the 1860s and 1870s, Indians competed not only with

other tribes for buffalo but with Anglo hunters who

swarmed over the Plains taking adavntage of the lucrative

hide market. Photo courtesy of the Center for American

History, Caldwell Collection (#CN 10189), The University

of Texas at Austin. Click to view full image.

|

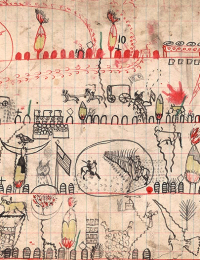

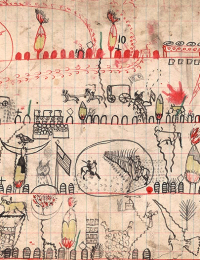

Rich in imagery, a page from a circa

1890s Kiowa diary, drawn on a soldier's target practice

book, indicates sweeping changes on the frontier. Note

soldiers, wagon trains, flags, and Longhorn cattle dominating

the scene with few tipis and other Indian symbols. Silver

Horn Kiowa drawing, courtesy National Anthropological

Archives, Smithsonian Institution (NAA INV 09063724).

Click for full image.

|

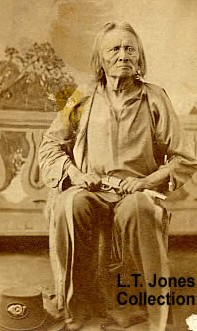

Quanah Parker, Quahahda Comanche

chief. Quanah's band would be the last of the Comanche

to submit to white dominion.

|

|

|

Beef issue. Kiowa women cut up government-issued

beef. Photo, circa 1892, courtesy of the National Anthropological

Archives, Smithsonian Institution (NEG 1454 A).

|

Indians at Fort Marion. Indians of

various tribes who were captured in the Texas Red River

Wars and other Indian battles of the late 19th century

were imprisoned at this Florida military fort. Photo

ca. 1860s-1930s, courtesy the National Anthropological

Archives, Smithsonian Institution (Lot 90-1 INV 09854500).

|

|

The Anglo-Texans' beleaguered former Indian

allies did not fare even that well. The small Tonkawa village

that grew up near Fort Griffin in the 1870s took in a small

Lipan band before the post closed in 1881. In 1890, only 56

Tonkawa had survived the tribe's second removal from Texas.

They were joined in Indian Territory by 20 Lipan.

The U.S. government adopted a new Indian policy in 1887, one

calculated to destroy the remaining tribal organizations.

The Dawes Act—also known as the "allotment"

or "severalty" act—provided for the breakup

of the reservations, with each head of a reservation family

being allotted 160 acres, each single adult 80 acres, and

each minor 40 acres.

The former Texas Indian tribes reached the end

of a long and deadly road at the beginning of the 20th Century.

The impact of the Dawes Act is amply illustrated by the allotment

of the Comanche-Kiowa reservation lands in 1901. About 440,000

acres were allotted to the 2,759 individual members of the

Comanche, Kiowa, and Kiowa Apache tribes, and about 550,000

acres were reserved for tribal use. The remaining 2 million

acres of the nearly 3 million-acre reservation were opened

to white settlement.

In 1906, the secretary of the interior sold

all but about 70,000 acres of the pasture that had been set

aside for the common use of the Comanche, Kiowa, and Kiowa

Apache. They had still been fearsome warriors in 1867, when

they met the U.S. peace commissioners at Medicine Lodge Creek

and bargained for the best future they could convince the

government to let them keep.

Forty years later, they had 17 per cent of it.

|

Tonkawa Chief Campo. In spite of

performing valued service as scouts for the U.S. Army

at Fort Griffin, the Tonkawa were removed to Indian

Territory after the post closed. View

large image. |

Pupils at Carlisle Indian school,

Pennsylvania. Established in 1879 by Richard Pratt,

the school attempted to assimilate Indian children into

the "white man's world" through education

and financial support. Among its students were four

of Comanche chief Quanah Parker's children and those

of others involved in the Texas Indian Wars.

|

|

|

Credits & Sources

The Passing of the Indian Era was written

by Steve Dial, Contributing Editor to Texas Beyond History

(see Frontier Forts Supporters

and Contributors).

Read more about historic Indian groups, including Kiowa and Apache, in the Texas Beyond History exhibits, Native Peoples of the Texas Plateaus and Canyonlands http://www.texasbeyondhistory.net/plateaus/peoples/index.html

Print Sources

Betty, Gerald

2002 Comanche Society Before the Reservation, Texas A&M

University Press, College

Station.

Catlin, George

1926 North American Indians, Vol. II. John Grant, Edinburgh.

Ewers, John C.

1997 "The Influence of Epidemics on the Indian Populations

and Cultures of Texas," in John C. Ewers, Plains Indian

History and Culture, University of Oklahoma Press, Norman.

Flores, Dan

1991 "Bison Ecology and Bison Diplomacy: The Southern Plains

from 1800 to 1850,"

The Journal of American History, Vol. 78, Issue 2 (September,

1991).

Foster, Morris W. and Martha McCollough

2001 "Plains Apache" in Handbook of North American

Indians, Raymond J. DeMallie, ed., Smithsonian Institution,

Washington.

Himmel, Kelly F.

1999 The Conquest of the Karankawas and the Tonkawas, 1821-1859,

Texas A&M Universsity Press, College Station.

Kavanagh, Thomas W.

2001 "Comanche" in Handbook of North American Indians,

Vol 13, Raymond J. DeMallie, ed., Smithsonian Institution, Washington.

Kenner, Charles L.

1969 The Comanchero Frontier: A History of New Mexican-Plains

Indian Relations,

University of Oklahoma Press, Norman, 1994 paperback edition.

Koch, Lena Clara

1922 "The Federal Indian Policy in Texas, 1845-1860,"

M.A. Thesis, University of Texas. Published in Southwestern Historical

Quarterly XXVIII, XXIX, Texas State Historical Association,

Austin.

Levy, Jerrold E.

2001 "Kiowa" in Handbook of North American Indians,

Vol. 13, Raymond J. DeMallie, ed., Smithsonian Institution, Washington.

Marks, Paula Mitchell

1998 In a Barren Land: American Indian Dispossession and Survival,

William Morrow and Company, New York.

Mayhall, Mildred P.

1939 The Indians of Texas: The Atakapa, the Karnakawa, the Tonkawa. Doctoral Thesis, The University of Texas at Austin.

Newcomb, W.W., Jr.

1961 The Indians of Texas from Prehistoric to Modern Times,

University of Texas Press, Austin, 1984 paperback edition.

1978 German Artist on the Texas Frontier: Friedrich

Richard Petri. University of Texas Press. Austin.

2001 "Wichita" in Handbook of North American

Indians, Vol. 13, Raymond J. DeMallie, ed., Smithsonian Institution,

Washington.

Noel, Virginia Pink

1924 The United States Indian Reservations in Texas 1854-1859.

Master's thesis, The University of Texas at Austin. Copy on file,

TARL Library.

Opler, Morris E.

2001 "Lipan Apache" in Handbook of North American Indians,

Vol. 13, Raymond J. DeMallie, ed., Smithsonian Institution, Washington.

Smith, David Paul

1992 Frontier Defense in the Civil War: Texas' Rangers and Rebels,

Texas A&M University Press.

Wade, Maria F.

2003 The Native Americans of the Texas Edwards Plateau, 1582-1799,

University of Texas Press, Austin.

Wallace, Ernest, and E. Adamson Hoebel

1952 The Comanches: Lords of the South Plains, University

of Oklahoma Press paperback edition 1986.

Weber, David J.

1982 The Mexican Frontier, 1821-1846: The American Southwest

Under Mexico. University of New Mexico Press, Albuquerque.

Links

http://www.texasindians.com/

Well-constructed site with numerous pages about different Indian

groups, teachers and kids activities, and links to many other sites.

http://www.tpwd.state.tx.us/edu/indian/isplash.htm

A good site for kids with information and activities from the Texas

Parks and Wildlife Department.

http://www.comanchelodge.com/

Interesting site that has the text of several important

treaties, including Camp Holmes, Tehuacana, Little Arkansas, and

Medicine Lodge, and the names and divisional affiliations of the

signatories, when known.

http://members.tripod.com/~PHILKON/links12apache.html

Extensive list of links to Apache websites.

http://www.tshaonline.org/handbook/online/

Handbook of Texas Online. Suggested search topics:

Apache Indians

Atakapan Indians

Caddo Indians

Cherokee Indians

Coahuiltecan Indans

Comanche Indians

Delaware Indians

Jumano Indians

Kickapoo Indians

Kiowa Apache Indians

Kiowa Indians

Seminole Indians

Tawakoni Indians

Wichita Indians

|