Research Objectives

During our initial visit to Hinds Cave in 1974, we mapped the site and examined the walls of several recent looter holes. Despite the site’s disturbed condition, it was apparent that substantial stratified deposits remained intact and that these were laden with perishable remains. Here, we realized, was a site that could fill a major research gap revealed by the 1959-1969 archeological salvage program at Amistad Reservoir. Ecological approaches had come to the forefront of archeological research in the 1960s with the realization that human societies, especially hunting and gathering societies, were intimately and inseparably connected to the natural environment. The dry rockshelters found at Amistad and in the surrounding the canyonlands were ideally suited for ecologically minded research, but most of the archeological research previously done there focused on culture history and chronology (see Before Amistad).

The testing at Parida Cave and excavation at Conejo Shelter in 1967-68 by archeologist Robert Alexander were useful steps in the right direction. For instance, modest samples of coprolites (dried human feces) were recovered and studied from both sites. David Riskind's 1970 analysis of the coprolies from Parida Cave was the first study of Lower Pecos coprolites ever published. The coprolites from Conejo Shelter were the first to be fully analyzed by Vaughn Bryant from the Lower Pecos region.

The stratigraphic complexity evident in both sites, however, proved quite challenging as did the logistics, sampling, and analytical requirements needed to effectively investigate perishable deposits. A full-scale ecologically oriented investigation of a dry rockshelter would have required far more concerted research effort than was possible within the limited scope of the Amistad salvage work. The work at Conejo Shelter provided only a brief snapshot of the dietary habits of Late Archaic peoples, but did point the way for the Hinds Cave project. At Hinds, the perishable deposits seemed likely to span most of the Archaic era and to contain many coprolites that could be used to greatly expand the studies of ancient diets.

The goal for the first season at Hinds Cave in the summer of 1975 was to excavate the perishable deposits to obtain quantifiable samples of all material culture, especially plant macrofossils and coprolites. We anticipated recovering a wide range of perishable and non-perishable artifacts within the site’s stratified contexts. Our specific objectives were designed to take advantage of the opportunity afforded by the deep perishable deposits. These were:

- Secure a well-controlled sample of prehistoric human coprolites from levels believed to be Middle Archaic in age (roughly 1,500-3,000 B.C.).

- Secure a well-controlled sample of plant macro fossils.

- Determine the depth of the cultural deposits.

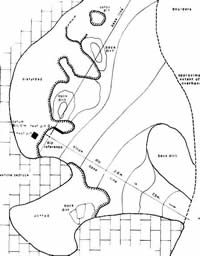

- Conduct an environmental resource study of the catchment area around the cave.

- Secure a well-controlled sample of material culture elements through excavation by natural layers.

- Establishing a site chronology.

Excellent progress toward fulfilling these objectives was made during the first season. Block A yielded a finely stratified record of plant macro fossils, artifacts, and faunal remains, while Area B sampled a deeply stratified latrine deposit that yielded several hundred coprolites dating to Early Archaic times. We had not reached bottom in either excavation. We also discovered that relic hunters had only stripped off the upper one-meter thick fiber layer in the back of the cave, leaving undisturbed lower deposits of unknown depth. Plans were immediately made for a second season.

The objectives for the second season (1976) were designed to sample the lower deposit at the site in both areas A and B.

- Complete the systematic sampling of Block A for plant macro fossils.

- Complete the systematic sampling of Block B to secure Early Archaic coprolites and explore latrine areas in the lower deposits.

- Expand Area A excavations to include the undisturbed deposits at the rear of the cave, in what was to become the A-C trench and Area C.

- Conduct a lithic resource survey of the catchment area around the cave. (We had identified chert debitage and artifacts made from chert that outcrops in below the site.)

Research objectives for the dietary study in addition to those listed above were:

- Recover as many prehistoric human coprolites as possible from each intact layer.

- Collect controlled samples of food plant remains from the excavations.

- Collect controlled samples of faunal remains.

Research objectives for the botanical study included:

- Extensive comparative collection of native plants in the site catchment area.

- Quantitative studies of local plant communities to determine seasonal and numerical availability of economic plants.

- Collect modern pollen control samples from upland soils and also from pools of trapped water in the canyon bottom in preparation for background pollen studies for the coprolite analyses.

- Collect plant remains from each cultural zone and lens.

- Examine site sediments for changes in time of economic plant use that might indicate paleoenvironmental changes.

- Construct a paleoenvironmental record based on pollen profile from cave deposits.

- Construct recent vegetation changes based on ethnographic and historical documents.

Every day during excavations dozens of bags of artifacts and matrix (sediment samples), fine and course fraction, were carefully collected and hauled back to camp. TAMU Anthropology archives.

Every day during excavations dozens of bags of artifacts and matrix (sediment samples), fine and course fraction, were carefully collected and hauled back to camp. TAMU Anthropology archives.