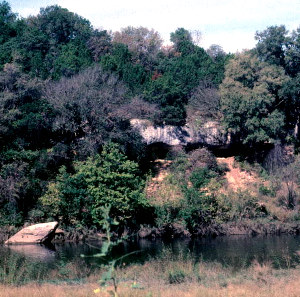

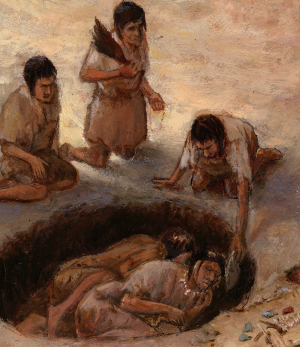

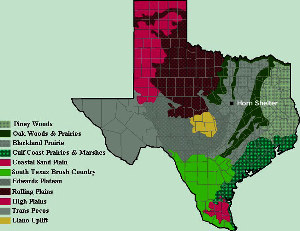

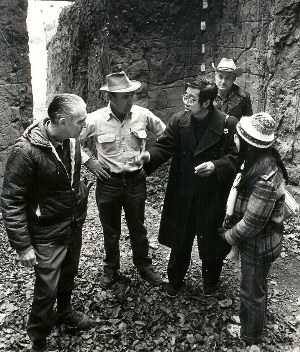

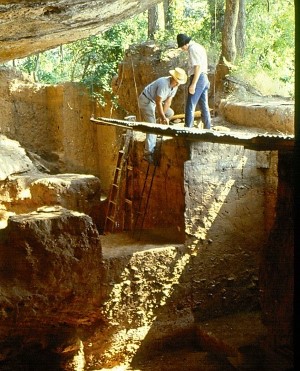

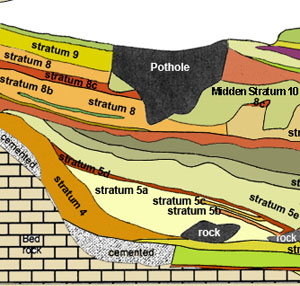

Working within the dark recesses of a rock shelter overlooking the Brazos River, avocational archeologists uncovered a deeply buried human grave of such significance that it has drawn the attention of researchers around the world. Dated to more than 11,000 years ago, the grave held the remains of a man and a child who had been buried with a cache of special offerings crafted of shell, bone, and stone. Horn Shelter No. 2 was filled almost to the top when Albert Redder, Frank Watt, and Robert Forrester began their work at the site in the late 1960s. They dug through nearly 20 feet of deposits, uncovering the fire hearths and trash left behind by a succession of campers in the shelter, from the early Paleoindian period —Clovis and Folsom—to more modern times, when squatters, or perhaps bootleggers, took up residence there during the Prohibition era. Later visitors—relic collectors—also left their mark on the shelter, destroying large portions of a buried Archaic burned rock midden and hauling away untold numbers of artifacts. During the decades of their excavations, the archeological investigators carefully followed the shelter's natural and human-made layers, recovering thousands of chipped-stone tools, animal bones, shell, charcoal, and other traces of the past. They identified and mapped 27 layers, or strata, revealing a record of human occupation from Paleoindian through historic times. In the laboratory, Redder cleaned and catalogued the artifacts and fine-screened hundreds of pounds of sediment, searching for small seeds, bones, beads, and other diminutive remains to help reconstruct the lifeways and traditions of past peoples. Samples of organic materials submitted for radiocarbon assay have yielded a series of dates from multiple levels, including charcoal fragments from an early, rockless hearth from more than 12,500 years ago. Because of these systematic efforts, both in the field and in the lab, the Horn Shelter collection is a treasure trove for researchers. The archives and artifacts recovered by both Redder and Forrester have been donated to the Smithsonian Institution National Museum of Natural History where they will undergo further analyses. Paleoindian Peoples at Horn ShelterWhile all the findings from the site are important for understanding human life in the past, the unusual double grave and abundant cultural materials recovered from the well-stratified Paleoindian layers make Horn Shelter particularly significant. As archeologist Dee Ann Story has noted, it is extremely rare to find such ancient materials preserved in good stratigraphic context. Fourteen strata identified at the site— almost two-thirds of the shelter's deposits—pertain to early occupations (ca. 9,000 to 12,500 years ago) based on radiocarbon dates and diagnostic projectile points and tools. Among these are a Clovis blade, a possible Suwanee or waisted Clovis point, Folsom, Brazos Fishtail (San Patrice-like), Wilson, Scottsbluff, and a number of unfluted lanceolate points resembling Dalton, Golindrina, and Barber. The Paleoindian grave uncovered midway in the shelter's deposits is one of only a few of such antiquity in North America, providing a compelling glimpse of how late Ice Age people attended to their dead. The relative completeness of the early human remains and abundance and variety of grave inclusions make this feature unique. Ongoing scientific analysis of the skeletal remains indicates the Horn Shelter people did not resemble modern Native Americans. Distinctive dart points found in the layer from which the grave was dug, as well as the layers above and below it, suggest this early group may have been connected to San Patrice and Dalton cultures common at the time in the southeast. Origins of these and other early peoples in North America is the subject of intensive study and debate among researchers. Judging from the camping debris left over the millennia, the Paleoindian peoples of Horn Shelter periodically hunted bison and deer but clearly depended upon a wide variety of much smaller animals for food. They cooked their food and warmed themselves with small, rockless fires built directly on the ground, and carried out a variety of other tasks nearby. Although the analyses of materials is not yet complete, nor the full story of Horn Shelter written, this exhibit provides examples of some of the most significant discoveries at the site and establishes a broad framework for understanding life at the shelter. The Site and Its SettingHorn Shelter No. 2 (41BQ46) lies in eastern Bosque County at the juncture of the Blackland Prairies and Cross Timbers ecological regions. This mix of prairies, woodlands and savanna environs afforded the occupants of Horn Shelter a rich array of natural resources to hunt and gather. Historically, the tallgrass prairies and wooded edges were home to numerous animals—deer, and at times, bison, as well as rabbits and other small mammals—and a variety of useful plants and trees. A dependable source of water, the Brazos River and its numerous small tributaries provided habitat for a variety of fish, waterfowl, turtles, mussels, and other aquatic creatures. The Brazos River flows in a sinuous route from the High Plains southeastward for more than 400 miles, passes in a wide bend in front of Horn Shelter, and travels another 400 miles to the Gulf of Mexico. During heavy flooding, the river periodically runs red with sediments carried downstream from the Rolling Plains. Some of these red clays appear in thin alluvial deposits within the shelter. Today the shelter lies 60 feet from the river's edge, with the bedrock floor roughly 15 feet above the normal water level. Given this proximity, and based on hydrology and river flow, the shelter was vulnerable to floods in the past, and its interior deposits could have been swept away during periodic rises of the Brazos River. Although there are indications the shelter was inundated on several occasions, large portions of the lower strata appear relatively intact. During earlier times, the river may have meandered toward the opposite bank, rather than along the limestone bluffs encasing the site. Climatic conditions in the past also played a role in preserving the Horn Shelter site. In his 2001 geologic analysis of the shelter's deposits (those remaining after archeological excavations), Shane Prochnow found only infrequent evidence of severe flooding in the lower units. These deposits apparently formed during the Younger Dryas, a climatic interval characterized by cooler conditions. During this time, deposits inside Horn Shelter largely derived from interior roof fall and weathering of the limestone walls. (It was this "cave fill," labeled Stratum 5 by Albert Redder during excavations, that held the Brazos Fishtail occupational layers, including the burial.) In later, overlying deposits, Prochnow saw evidence of more frequent and moderately severe floods reaching inside the shelter. The absence of Early Archaic cultural remains at the site may be attributable to scouring of deposits during this time. Given natural and human forces threatening the site over time, the systematic excavation of Horn Shelter is remarkable. Floodwaters, relic collectors, and campers have disturbed or destroyed cultural deposits in other rockshelter sites along the Brazos River. As Redder has noted, such damage results in an irretrievable loss of knowledge. "A layered archeological site such as Horn Shelter is like a huge book of information," he says. "Rip out a page or a single chapter without carefully reading every sentence and the story is changed or lost forever." In This ExhibitMore than 50 years since its discovery, the Horn Shelter site is not widely known outside academic and research communities. For this reason, Texas Beyond History has collaborated with Albert Redder, the Bosque Museum in Clifton, and other museums and researchers to bring the fascinating story of Horn Shelter to a larger audience. In the following sections, we trace the long succession of peoples who camped in the shelter and highlight the efforts of avocational archeologists to bring the ancient stories to light. The Investigations section chronicles the long journey of Albert Redder, Frank Watt, and Robert Forrester to excavate and document the deep site. Reading the Layers provides an interactive look at the shelter’s complex stratigraphy, depositional processes, and some of the most significant artifacts and features found in the various strata. By clicking on specific layers or layer buttons, viewers can access more than 20 separate pages with data and images from each stratum. This section also includes an overview of stratigraphy, a locational graphic of key artifacts and features, and a chart of radiocarbon data. Archaic Fishhook Manufacturing focuses on the intricate bone hooks, hookmaking tools, and manufacturing debris, recovered largely from the upper levels of the site, and traces the processes involved in this technology. A Paleoindian Grave examines the rare double burial of two individuals and provides a detailed look at the grave items. Horn Shelter and Beyond synthesizes findings and considers the site in context with other early grave sites. Credits and Sources provides brief biographical sketches of the Horn Shelter researchers as well as references and links for learning more about topics covered in the exhibit. Editorial NoteSince its inception in 2001, Texas Beyond History has maintained a policy of not showing photographs of Native American remains. Because of the extreme age and importance of the Paleoindian double grave at Horn shelter, we have chosen to make several photos of the grave and human remains available for researchers. However, only renderings or drawings are used on the main webpages. Photos can be accessed only within the secondary image pages.

|

|