Investigations

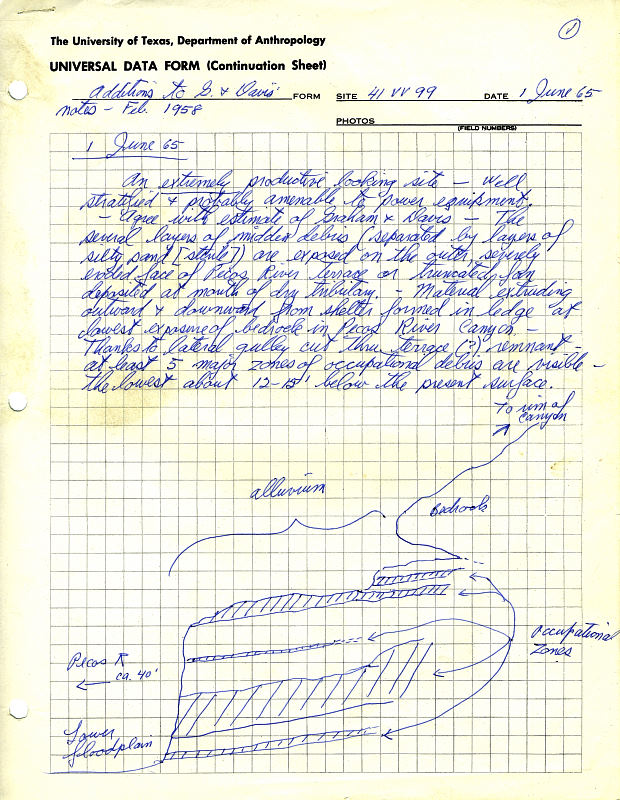

In 1958, the Texas Archeological Salvage Project (TASP) at the University of Texas was contracted by the National Park Service to carry out archeological and environmental research in the area that was to be flooded by the proposed Diablo Reservoir (renamed the Amistad Reservoir). The lake would be created by the construction of a huge dam across the Rio Grande just downstream from its confluences with the Pecos and Devils rivers, near the twin cities of Del Rio, Texas, and Ciudad Acuna, Mexico. While carrying out the first survey of the area in the early spring of that year, archeologists John A. Graham and William A. Davis discovered Arenosa Shelter. Arenosa was situated on an alluvial terrace of the Pecos River that had been created by periodic floods of the Pecos and Rio Grande. Erosion of the terrace edge had exposed a 15 foot vertical cutbank face containing layers of ash, burned rock, bone, shell, and other cultural materials separated by layers of sand and silt. Graham and Davis observed that the layers of cultural material extended for some 50 feet along the face of the terrace and at least 25 feet back into the terrace, where it narrowly passed beneath a limestone overhang amidst dense vegetation. The men recognized the site's research potential. Before the terrace had built up to its present thickness there must have been sufficient head clearance for human occupation of the shelter formed by the overhang, and it is quite likely that Site VV99 is actually a rockshelter site with a developmental terrace involvement. [It] offers the possibility of a well-defined stratigraphic sequence in a combination rockshelter-stream terrace site. Since it will be entirely beneath the conservation pool of Diablo Reservoir, its excavation is strongly urged. — Graham and Davis 1958 The site that came to be known as Arenosa Shelter was not, however, one of the “most spectacular” sites identified by Graham and Davis during the survey and it was not selected for immediate excavation. Instead the early work focused on the rockshelters with dry deposits containing well-preserved organic remains. Arenosa was visited again on June 1, 1965 by archeologists Dave Dibble and Elton Prewitt. They were seeking a deeply stratified site suitable for excavation. By crawling through the thick brush growing on top of the river terrace, Prewitt confirmed that VV99 contained a buried rockshelter. They were impressed with the site's promise and agreed with Graham and Davis’ recommendation that it be excavated. As Dibble put it in his daily note, "an extremely productive looking site — well stratified and probably amenable to power equipment." Dibble revisited Arenosa with his newlywed wife, Anne, in July of that year as he made plans for the fall field season in the Amistad area. Dibble’s original opinion of the site’s importance was reinforced by his second visit, and he decided to postpone a scheduled third season of work at the Devil’s Mouth site in order to excavate Arenosa in the fall. See Before Amistad to learn more of the history of the 1958-1969 "Amistad archeological salvage program." |

|

|

|

|

|

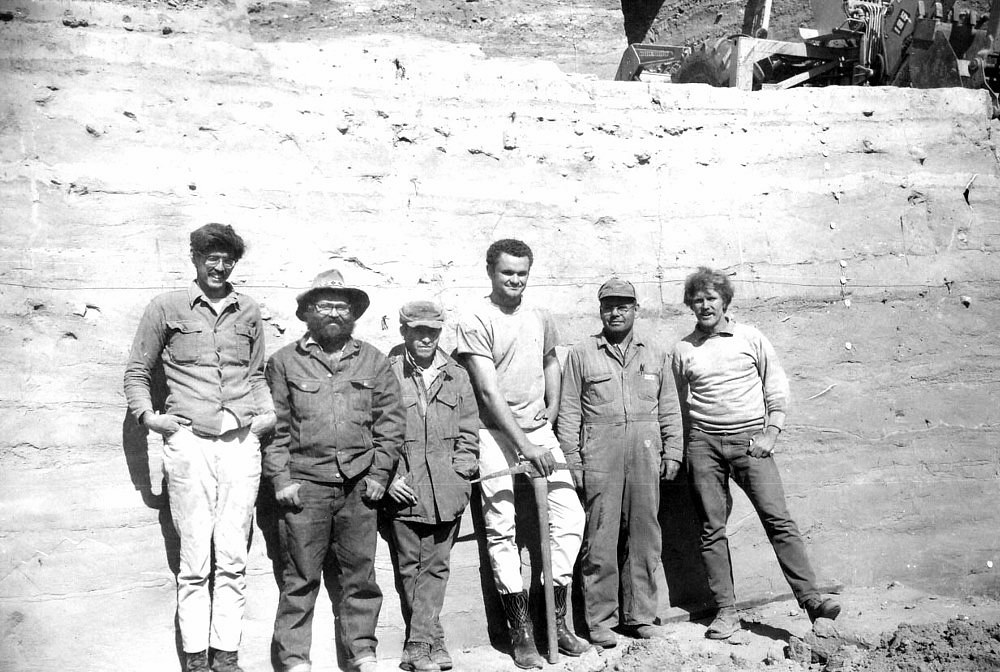

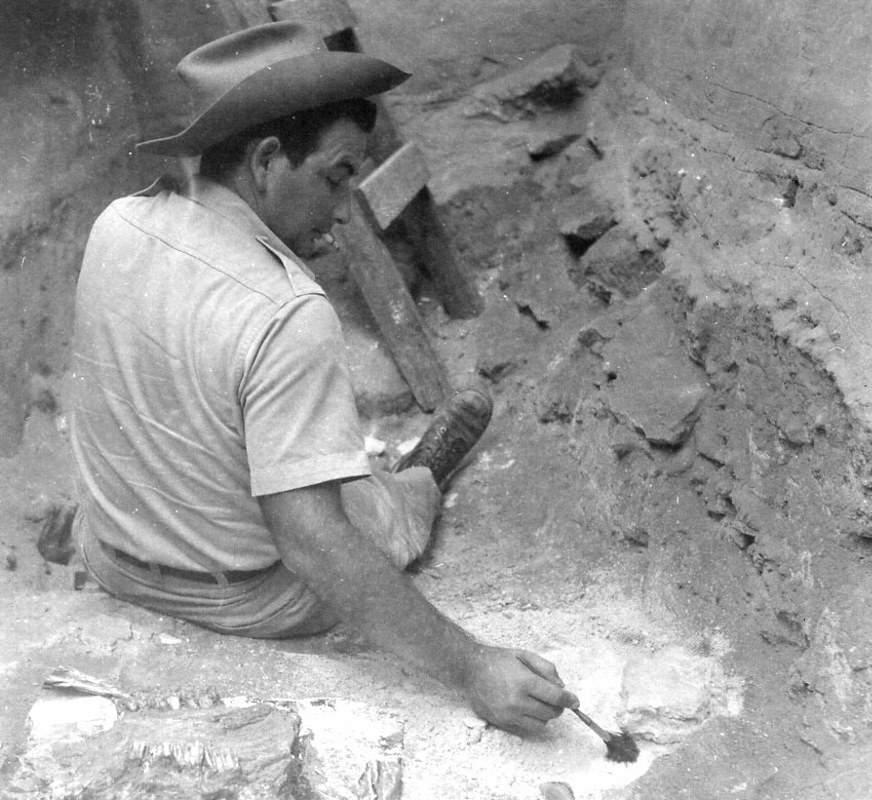

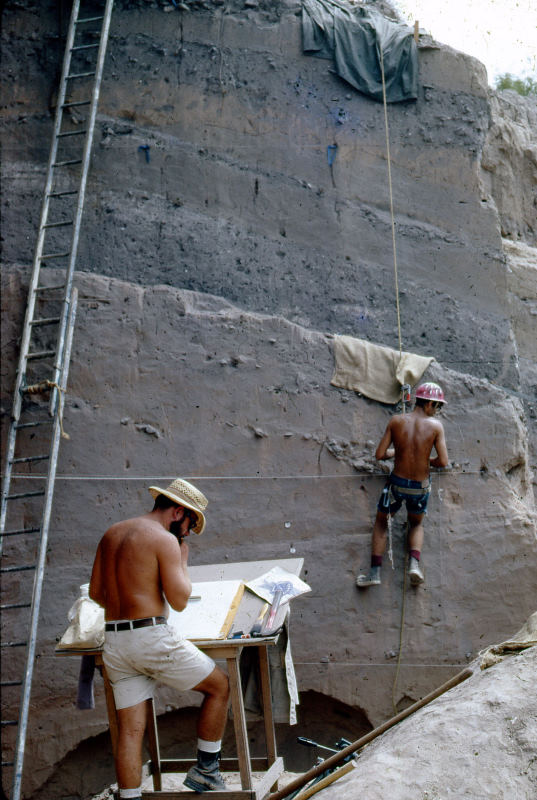

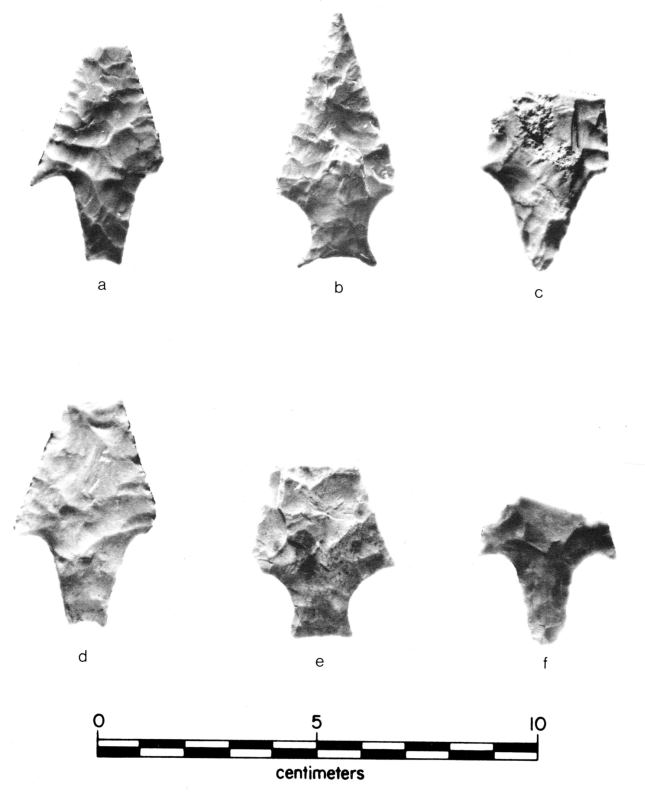

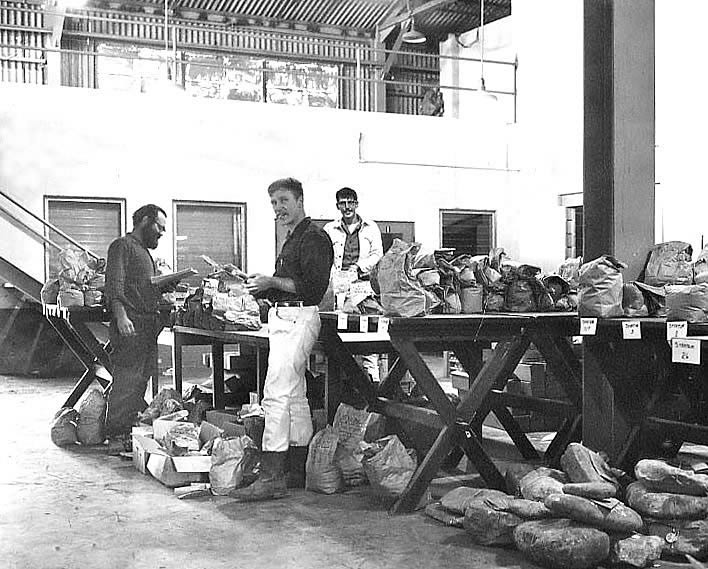

Excavations, 1965-1968Excavation began at Arenosa on October 13, 1965 by a crew of eight men from TASP under the direction of Dibble. The crew included graduate and undergraduate students from the University of Texas as well as several local workers who had been trained as field archeologists by Dibble during the 1963-1964 excavations at Bonfire Shelter. After mapping the site and clearing off the dense vegetation, a backhoe was used to remove erosion-jumbled terrace, creating two large parallel trenches. Skilled backhoe operator Harold Beall cut a third trench perpendicular to the first two, isolating a block of sediment that was visible on three faces. This made it possible to recognize and trace individual layers in the block’s stratigraphy, allowing the excavators to “peel” these layers off one by one using hand tools. The crew’s attention was initially focused on this first excavation block, but was later directed toward a second block created in the same manner as the first. By the time the field season ended on February 3, 1966, they had dug through 31 feet of deposits and identified 37 different layers in the site’s stratigraphy. In the deepest block the crew had been forced to halt their excavations when they encountered a huge roof spall that they dubbed “Big Mother Rock.” Convinced that Big Mother Rock was not the bottom of Arenosa Shelter, Dibble led a second season of excavation at the site from June 26 through September 26, 1967. The crew enlarged the central excavation block toward the back of the shelter in an attempt to see how far back Big Mother Rock extended. By the time they reached the edge of the giant rock, however, the field season was nearly over and the crew had time to dig only a single 5-x-5-foot excavation unit behind Big Mother Rock into the deep layers of the shelter. In that unit they found Early Archaic projectile points and bone from an extinct form of bison—tantalizing evidence that deeply buried cultural deposits extended behind and beneath the giant rock. By this point, TASP’s attention was focused on other sites in the Amistad area and Dibble himself was enrolled in graduate school at Washington State University, leaving little support for continued work at Arenosa. Dibble managed to get a small crew together for a final month of field work from July 2 to August 1, 1968. Their plan was to excavate several more units between the one opened at the end of the 1967 season and the back of the shelter, in order to get a larger sample of the early cultural materials surrounding Big Mother Rock. To accomplish this, it was necessary to move the rear wall of the central excavation block back 15 feet, nearly to the back of the shelter. This meant destroying a large section of the upper deposits, but the deep hand excavations would not have been possible otherwise, given the limited time and personnel. To accomplish this job Dibble dispatched Prewitt and Beall to Arenosa with the backhoe and a small crew a few days ahead of the rest of the crew. Prewitt’s team quickly removed the what they dubbed “Dibble’s Hypotenuse” with the backhoe and troweled cleaned the new rear wall, creating a beautiful profile that was simply 15 feet closer to back of the shelter than it had been the year before. The crew then set up a line of 5-x-7-foot units placed roughly parallel to the back of the shelter (the odd size dictated by the available space), and dug rapidly to get to the deposits below and behind Big Mother Rock. They documented a series of additional layers, the deepest of which did not contain definitive cultural remains. Finally they were halted by a series of large slabs of rock wedged tightly together about 42 feet below the original ground surface. Though this was probably not the floor of the shelter, time had run out and the excavations at Arenosa came to a close. During the final weeks detailed drawings and photographs were made of the deep layers. The crew and several visiting researchers took advantage of the exposed excavation walls to collect a variety of soil samples to be used for pollen studies and other specialized analyses. For instance, Frank Leonhardy of Washington State University came down to collect soil column samples (monoliths), to provide the basis for for geomorphological interpretation of the site's depositional history. After three seasons of field work at Arenosa, Dibble and his crew had exposed a series of deposits 42 feet in total thickness that consisted of 49 identifiable layers, half of which contained cultural remains. Over 500,000 items were catalogued from the site, including about 16,000 stone artifacts, over 47,000 pieces of bone, about 32,000 snail shells, nearly 9,000 mussel shells, and numerous geologic samples. Of the stone artifacts, over 2000 were identified as projectile points, 141 as painted pebbles, and 121 as groundstone. Some 1,000 pieces of bone were identified as artifacts, including about 500 awls and 200 beads. |

|

|

|

|

|

AnalysesAfter the Arenosa excavations ended, analysis of the many artifacts and geologic samples recovered from the site began. Initial identification of many of the artifacts was carried out by Dibble himself along with other TASP staff (including Harry J. Shafer and Vaughn M. Bryant), as well as volunteers Harold E. Lieck, Richard Hulbert, and many others. But the NPS funding dried up soon after Arenosa Reservoir began filling up in 1969. Arenosa Shelter was one of several important Arenosa sites that lingered unreported. The first detailed analysis of materials from Arenosa was undertaken by Michael B. Collins. In a Ph.D. dissertation that he completed in 1974, Collins studied the lithic artifacts and debris from Arenosa in order to identify patterns of stone tool manufacture at the site through time. He found that throughout the site’s occupation, river cobble chert from the streambed of the nearby Pecos River was the favored material for making stone tools, and that it was frequently heat treated as part of the manufacturing process. Collins’ work on Arenosa’s lithic materials was quickly followed by analysis of the site’s stratigraphy by geologist Peter C. Patton. Patton studied the soil samples and monoliths taken from Arenosa in order to reconstruct the history of flooding at the site. Dibble encouraged the study and helped secure additional radiocarbon dates to pin down the timing of the site formation. Patton realized that Arenosa had been flooded repeatedly by both the Pecos and Rio Grande over the last 11,000 years, including at least ten truly massive floods between about 9000 and 1500 B.C. Patton completed his dissertation in 1977 and in 1982 he and Dibble published an often-cited article on the subject in the American Journal of Science. In 1987, Shirley B. Mock completed a Master’s thesis that analyzed the motifs of and sought the meaning behind the painted pebbles from Arenosa and other sites in the Amistad area. In 1991, Leland C. Bement published a statistical study of Middle Archaic dart points from Arenosa. His goal was to determine whether any of the generally recognized variations of the Langtry type dart point were distinct enough to merit division into separate dart point types. His analysis seemed to confirm that “Langtry” and “Val Verde” points were indeed distinct enough to be considered separate dart point types, and Bement identified a third distinct dart point type that he dubbed “Arenosa.” Bement's study was included in Papers on Lower Pecos Prehistory, edited by Solveig A. Turpin. Turpin's own paper summarized the radiocarbon record of the region and made use of the radiocarbon dates from Arenosa to help construct a radiocarbon chronology for the Lower Pecos. The framework was based on a 12-part chronology that had been informally proposed by Dibble. Turpin's compilation was the first time all of the radiocarbon dates from Arenosa Shelter had been published. A third paper in the 1991 volume reported the results of trace element analysis that they had performed on three obsidian flakes recovered from a Late Archaic stratum of Arenosa. Thomas R. Hester and four co-authors determined that the obsidian had originated hundreds of miles away in the Jemez Mountains east of Sante Fe in north-central New Mexico. One of these obsidian arifacts is on display at the Texas State History Museum in Austin. The first comprehensive analysis of the site’s fauna was completed by Christopher Jurgens in 2005 for a Ph.D. dissertation. Jurgens was able to identify over 140 vertebrate taxa from Arenosa and determine how its bone tools and ornaments were used. He found that fish made up a significant part of the diet at Arenosa, and that prehistoric fishers often filleted fish and took special precautions to avoid being injured by catfish spines. Jurgens was also able to identify evidence in carnivore remains for “caping”-a specialized butchering technique that removes the skin of an animal while preserving the distinct facial features of its head. The results of the dissertation studies by Collins, Patton, and Jurgens are further discussed in the Half-Told Story section. |

|