|

From the time of its founding in 1718 to today, residents of the city of San Antonio have had to employ a variety of means to secure a steady supply of water. The Spaniards and Indians who originally founded the town used acequias, or irrigation canals, to distribute water from the San Antonio River to those who lived in the town and missions. In the late nineteenth century, a water reservoir was constructed at the site of the present-day Botanical Gardens to store water pumped from the river. By the twentieth century, San Antonians began to drill wells directly down into the source of the water in the San Antonio River, the Edwards Aquifer. Unfortunately, by the latter part of the century the growing population of San Antonio needed more water than could be supplied from the aquifer.

By the 1970s, the San Antonio City Planning Commission was forced to form a committee to attempt to find a supplemental water supply. In 1979, this committee recommended that the city begin construction on a surface water supply project that would be known as the Applewhite Reservoir. Though it would take the better part of ten years to secure all of the federal and state permits needed to begin construction on the reservoir, a site was chosen along a 7-mile stretch of the Medina River and initial work began in 1981. As part of this early work, the San Antonio Water System contracted with the Center for Archaeological Research (CAR) at the University of Texas at San Antonio to survey the project area for archeological sites that would be impacted or destroyed by construction of the reservoir and dam. In all, CAR archeologists discovered 78 archeological sites in the project area between 1981 and 1987.

By late 1989, the City had secured all the necessary permits for construction of the reservoir. Construction began and a second round of archeological studies was undertaken. This time, SAWS contracted with the Center for Ecological Archaeology (CEA) at Texas A&M University to complete the survey work, test excavate numerous sites, and carry out full-scale excavations at the most important sites. Numerous sites were tested in 1989 and 1990 and full-scale excavations began at the Beene site in late 1990 and continued into 1991. CEA's excavations at Beene took place in the midst of ongoing dam construction, creating a rather unique work environment where operators of earth moving equipment could discover archeological sites.

In May of 1991, the citizens of San Antonio voted to halt the Applewhite Reservoir project. Though this effectively ended archeological research in the project area, archeologists from Texas A&M were able to return to the area intermittently between 1995 and 2005 to carry out follow-up excavations and monitor the effects of erosion and mechanical stabilization of the site.

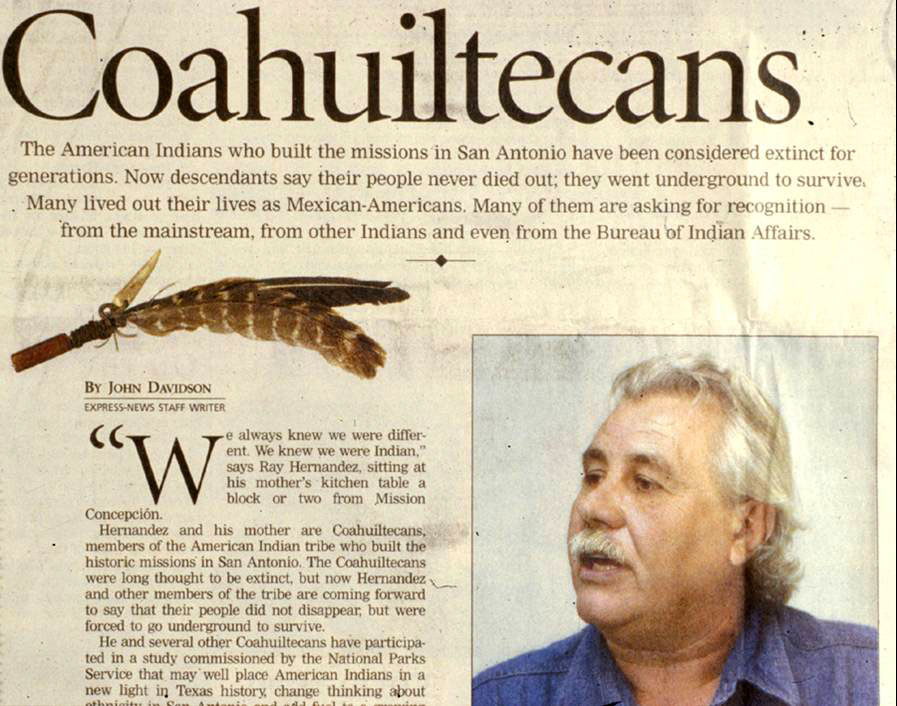

Though the reservoir project has been abandoned, the valuable cultural resources that lie within the project's boundaries will not be neglected. Archeologists who worked at the Richard Beene site have joined forces with several agencies and organizations, including the modern day descendants of protohistoric Indians living in south Texas, who collectively came to be known as Coahuiltecans, to develop the Land Heritage Institute of the Americas (LHIA) at the abandoned reservoir site. The LHIA is currently being developed by the Land Heritage Institute Foundation, a non-profit consortium, as an education, recreation, and research center for the study of ancient and contemporary lifeways in south Texas. These Coahuiltecan descendants, known as the Tap-Pilam-Coahuiltecan Nations (or simply Tap-Pilam), are an essential component to the LHIA. Some Tap-Pilam members are knowledgeable about indigenous cookery and others are actively engaged in trying to revive their languages. The Land Heritage Institute Foundation is an excellent example of how collaboration between Native American groups and members of the archeological community can yield fantastic results in the study of ancient lifeways.

|

The Spanish built acequias like this

one (located in Menard, TX) to channel water from the San Antonio River for use by the citizens of the

town.  |

The Medina River as it passes near the

site of the planned Applewhite Reservoir. The City of San Antonio sought to dam the Medina in

order to create a surface water supply for its citizens. Though construction on the reservoir began

in 1989, it was cut short after a voter referendum in 1991 ended funding for the project.  |

Archeologists excavating at Richard

Beene and other sites within the Applewhite Reservoir project area worked amongst the din of heavy

machinery working on the dam spillway. Sometimes the earth-moving equipment was used to further the

archeological excavations. In this picture, a backhoe removes overburden from one of the components

at the Richard Beene site.  |

Groups such as the Tap-Pilam Coahuiltecan Nations continue to fight for recognition by the federal government, scientists, and the general public. Fortunately, archeologists who carried out archeological research at the Richard Beene site and the Tap-Pilam worked together to help create the Land Heritage Institute of the Americas within the former Applewhite Reservoir project area.  |

|