|

||||

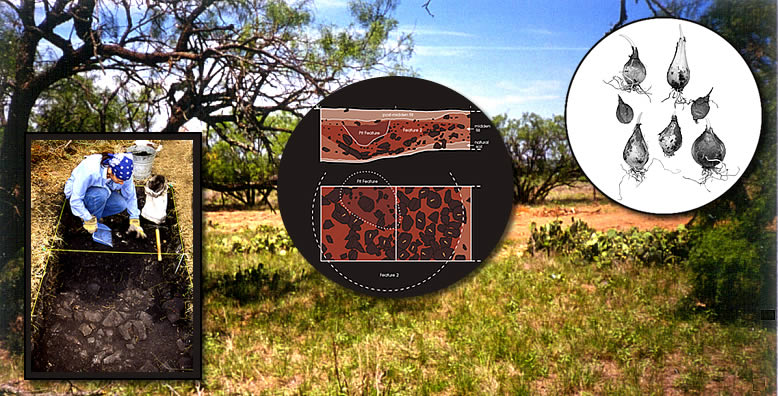

| A thousand years ago prehistoric hunters and gatherers—American Indians of unknown tribal affiliation—frequented the gently rolling hills of what is now Camp Bowie in Brown County near the geographical center of Texas. They were semi-nomadic people who lived in small bands much of the year. They moved from camp to camp across the landscape as the seasons waxed and waned and as the rains came or came not. When they lingered in the Camp Bowie area, they hunted deer and other game, searched for the right kinds of tool-making stones, and gathered fruits, nuts, and seeds. In the spring they gathered basketloads of wild onions and other small flowering plant bulbs and baked these in large rock-lined earth ovens built within shallow pits. The rocks they used for cooking broke apart after several heatings and were tossed out from the pit, forming donut-shaped mounded accumulations known to archeologists as burned rock middens. Recently, researchers from the University of Texas at San Antonio (UTSA) have explored these ancient campsites to learn more about what it was that drew prehistoric peoples to the area. Today Camp Bowie is a 9,297-acre training area for the Texas Army National Guard. The original Camp Bowie covered some 119,000 acres during World War II. After the war the land was declared surplus by the Federal government. The National Guard retained 5,000 acres and the remainder was sold to the public (including the entire area where most of war-related training structures had been built). Since the 1940s the National Guard has acquired the remaining 4297 acres. Camp Bowie is situated in central Texas, just north of the Edwards Plateau. The general vicinity was home to prehistoric peoples for over 12,000 years. For much of the last millennium of the prehistoric era, prior to the historic settlement of Brown County beginning in the mid-1800s, native groups frequented the area, camping near the numerous seasonal streams and springs, hunting game, collecting plants, making tools, and living off of the land. Burned rock middens are the area's most conspicuous reminder of prehistoric life; large piles of fire-fractured rock are easy to spot and resistant to erosion. For decades, these enigmatic accumulations of rock, found throughout much of central and western Texas, have confounded archeologists and landowners alike. But in recent years, new investigative approaches have yielded new insights into their use. At Camp Bowie, archeologists from the Center for Archaeological Research (CAR) at UTSA investigated 19 burned rock midden sites. The result is a wealth of new information about the prehistoric peoples of the region and the recovery of the largest collection of preserved plant food remains from earth ovens on the edge of the Southern Plains. The Archeology of Camp BowieCamp Bowie, like all of the nation's military training facilities, must comply with various federal and state laws designed to protect environmental and cultural resources, including important archeological sites. Under the terms of Section 110 of the National Historic Preservation Act of 1966, the Texas Army National Guard must inventory the cultural resources of Camp Bowie (and other facilities) and determine whether any resources present in the area are eligible for the National Register of Historic Places. The idea is to identify those places that contain the most important historic information and try to avoid these during training operations. To comply with the law, archeologists working for the Texas Army National Guard (TXARNG) began conducting systematic archeological surveys in 1993. They walked over nearly all of the camp in order to identify and record all prehistoric sites that are present within the camp boundaries. They also recorded a number of historic period structures: old farmsteads that were used before Camp Bowie was established; bridges, dams and other buildings constructed by Works Progress Administration (WPA) and Civilian Conservation Corps laborers; and World War II-era training facilities such as bunkers. The National Guard archeologists identified nearly 200 archeological sites—most of them dating to prehistoric times—during their survey. Many of these sites required additional investigation to determine their significance, based on the types of artifacts the sites contain, how old they are, and whether the sites would contribute to a better understanding of Texas prehistory. Beginning in 1999, CAR archeologists investigated several dozen sites and carried out small surveys of the remaining portions of Camp Bowie. The prehistoric sites on Camp Bowie range in size from large campsites to small camps containing only a sparse lithic scatter of broken flint artifacts. These are stone artifacts made of flint (properly termed chert) such as projectile points and knives as well as chipped stone debris resulting from tool manufacture. These small sites were probably occupied for a short time, perhaps just long enough to make dart point, butcher a deer, or camp for the night. Other prehistoric sites were places where people stayed for longer periods of time—perhaps days or sometimes even weeks. Such campsites typically have numerous stone tools as well as remains of cooking features (such as burned rock middens and individual hearths or ovens). It is likely that simple houses (brush huts or wickiups) were built at major campsites, but all traces of these have fallen victim to the ravages of time. At Camp Bowie, CAR archeologists focused mainly on the numerous burned rock middens dotting the 9,300-acre property. Ranging in shape from raised mounds to flat, dense, concentrations of burned or fire-cracked stone, these features mark places frequented by prehistoric cooks. The CAR archeologists investigated 19 middens to try to determine what was being cooked in them, in what season (or seasons) they were used, and when these sites were in use. In This ExhibitIn the sections below, readers can learn about how prehistoric peoples made use of the Camp Bowie area. Environments Past and Present provides a brief overview of the environmental change in the region, drawing on several lines of evidence. In What Is A Burned Rock Midden, readers are taken through an illustrated step-by-step "guide" to midden construction, summarizing current views of how middens formed. What the Middens Tell Us draws together findings from the Camp Bowie middens and others across the state. Of particular interest is a close-up look at the bulb foods—ranging from onions to violets—cooked by prehistoric chefs. We'll also speculate as to why these early inhabitants undertook the labor-intensive tasks of digging basketloads of tiny bulbs and hauling tons of rock for cooking them. Finally, we'll look at the spatial distribution of middens across Texas and consider additional evidence of plant food cooking. The Camp Bowie Middens exhibit on Texas Beyond History was made possible with funding through the Texas Army National Guard. The exhibit is intended to share some of what archeologists have learned with the public. |

||||