Site Investigations |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

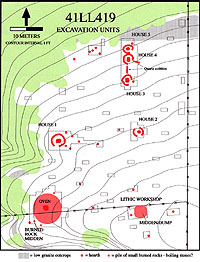

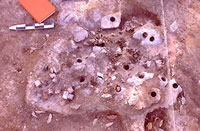

Before excavations began at the Graham-Applegate site in the summer of 1998, there was little evidence that the remains of a prehistoric encampment were buried only a few inches beneath the ground surface. A year earlier, the Llano Uplift Archeological Society had conducted a survey of the area at the request of the landowner, Charlotte Graham, and found only a few flint flakes. Since the soils at the site are shallow, it was felt at the time that if anything of archeological significance existed there, more artifacts or features would be visible on the surface. Reinforcing the idea that little would be found there was the fact that no permanent water flows in the immediate area today. The closest reliable source of water is the Llano River, a half-mile to the west over rough terrain. Early in 1998, the chance discovery by Ms. Graham of a half-dozen flint arrow points protruding from the backdirt piles of gopher holes provided the first real hints that something archeologically important might be buried there. All the arrow points were of the same type or "style" suggesting that only a single cultural group may have camped there. If so, it seemed the site could well be a time capsule containing information about life in central Texas at a particular period in the prehistoric past. In this case, the style of point was known to have been used between A.D. 700 and A.D. 1350, during what archeologists call the Austin Phase. Recognizing the site's potential importance, the Llano Uplift Archeological Society (LUAS) made the decision to undertake investigations at the site. Initially, the research plan was to excavate large areas where the arrow points were found and where it seemed the most intensive activity took place in prehistoric times. Our hope was that living surfaces would be exposed, perhaps even the remains of shelters or areas where specific activities, stone-tool making for example, took place. The shallow soils were ideal for a broad horizontal excavation (opening up large areas) since the hoped-for living surface could be reached quickly. At sites with deep archeological deposits, such as those on river terraces, excavated areas often are small due to the large volume of soil that must be removed. At the beginning of the investigations, we also hoped to recover a discrete (unmixed) assemblage of the kinds of stone tools used by people during the Austin phase. Few open campsites of this period have been investigated that do not also contain artifacts from earlier and later aboriginal cultures, mixed in with those of the Austin phase. A 4-x-6-meter (16.7-x-20-foot) area was initially excavated down to a depth of 25 centimeters (10 inches), revealing two small hearths to one side of an extensive refuse scatter of burned rock, mussel shells, and stone tools. Large numbers of flint flakes, along with cores and unfinished bifaces indicated that stone-tool making took place there. Three obsidian flakes also were found in this "lithic workshop" area. In the fall of 1998, LUAS obtained permission to do test excavations of the adjacent Applegate property that lies immediately to the north of where we were working. It was assumed at the time that the remains of the Austin phase occupation continued onto this property, although almost no artifacts were noticed in the gopher mounds that also dotted the surface of the Applegate land. Hidden Midden ExposedAt this point, we wanted to know not only how far the site extended to the north, but also the nature of the aboriginal occupation there: Would we still find the same kinds of artifacts and features? Would they date to the Austin phase or was this area occupied by earlier or later cultures? A series of 1-x-2-meter ( 3.3-x-6.7-foot) test pits was excavated at widely spaced intervals to the north and then to the east and west on the Applegate property in an attempt to answer these questions. These excavations showed that the Austin phase occupation continued at least 50 meters (167 feet) to the north with scattered hearths and stone tools although the amount of flint chipping debris decreased considerably. One of the test pits near the edge of a deeply cut arroyo that borders the west side of the site revealed what was at first thought to be an unusually large and elongated stone hearth. To better record this feature, adjacent units were excavated, and to our surprise, other stone features began to emerge. Only after an 2-x-5-meter (6.7-x-13.4-foot) area was opened up, however, did it become apparent that these rock features were related. Collectively they appeared to form the walls and central hearth of a large circular structure that was eventually designated "House 1." The finding of an apparent house was big news—it had been several decades since the last house remains had been found in central Texas. Archeologists from the Lower Colorado River Authority, TARL, and the Texas Historical Commission visited the site and offered opinions and encouragement. With the discovery and excavation of the first "house," our research plan was changed to actively seek out additional house-like features at the site. Since there were no clues on the surface to lead us to them, the only sure way of finding similar features was to cover as much of the site as possible with test units. This strategy initially failed to find additional "houses" but did lead to the discovery of a burned rock midden. Typically, burned rock middens are conspicuous features littered with fire-cracked rocks and often forming an obvious mound. But we only became aware of the one at Graham/Applegate through a randomly placed test pit which revealed an area of tightly packed, burned granite rocks with dark, charcoal-stained soil only inches below the surface. The midden had been all but invisible since it blended with the natural contours of the land and was hidden by dense brush and leaf litter near the edge of the arroyo only 15 m (50 ft) south of House 1. Over the next several months, the thin layer of soil and fallen leaves was carefully stripped away to expose the surface of the midden. It consisted of a low circular mound of burned granite rocks with a center of dark, charcoal-stained soil, presumably where the earth oven or ovens were located. The soils in the site area are a light tan color with little organic material, and the dark staining in the midden stands out very clearly (see photo of soil samples). A meter-wide trench was hand excavated down the middle of the midden to get a cross-section of the central oven and to locate the oven feature. Unfortunately, the trench missed the oven, which probably lies just to the west where large boulders are protruding from the surface. As one might expect for an area devoted to cooking, few stone tools or flakes were recovered from the midden excavations, but many food items were, including mussel shells, bone, and charred plant material. Probing for "Houses 2 and 3"Note: Since this exhibit was written, a more recent interpretation indicates the features first thought to be the remains of houses were more likely burned rock middens (see the New Interpretation section). After the midden excavations, it was realized that it would take far too much time to adequately cover the site with test pits in order to find additional "houses." We then began systematically probing the ground with thin metal rods to locate subsurface stone features. This was possible only after a rain had softened the ground, otherwise the sun-baked earth was much too hard for this technique. This approach was very successful and directly led to the discovery of possible Houses 2 and 3, both of which were missed by earlier test pits nearby. "House 4" also was discovered by probing, although before excavation it was initially thought to be a small cooking hearth. Bedrock near the surface along the north side of the site hampered the probing, and "House 5" was discovered more or less accidentally while excavating the area immediately to the north of "House 4." "Houses 3, 4, and 5" all lay within the same excavation block and exhibited similar construction details— what appeared to be triangular hearths, for example—and were probably built at the same time. Of interest here is a long, narrow, pile of quartz cobbles that connects "Houses 3 and 4," put there by the prehistoric inhabitants for some unknown reason. During the excavation of the block, evidence of a more-recent occupation was identified above, or on top of, the floor surfaces of the three presumed houses. One small cooking hearth and a small, rock-lined pit were apparently built on and in the shallow soils that developed over the "house" foundations after the site had been abandoned by the earlier people. A radiocarbon date from the small hearth places this later occupation some time between about A.D. 1000 to 1200. The Llano Uplift Archeological Society enjoyed what few professional archeologists today have, the luxury of time. While most government-mandated digs are done under intense time pressures in advance of bulldozers and development, excavations at Graham-Applegate were carried out over a three-year period (and still counting). As a result, few sites in central Texas have been as extensively excavated as Graham-Applegate. Even so, much still needs to be done to understand fully what was going on there centuries ago. With this site, we can learn how prehistoric encampments were organized and document the kinds of activities that took place there. Much will be learned, too, during the analysis phase of the project when the artifacts are scrutinized and other special technical studies carried out. We already know we are dealing with at least three different periods of occupations of the site, all by people of the Austin phase culture. The earliest known stay happened around A.D. 1000 when the rancheria was built. A second visit occurred probably less than a century later, and includes the hearth and rock-lined pit above "House 3." A final visit happened sometime in the 1300s, as revealed by a radiocarbon date from the "hearth that disappeared." The Hearth that DisappearedAlthough the location of the Graham/Applegate site is not a well-kept secret, we have been very fortunate that little vandalism has occurred in the three years of excavations. A few pieces of equipment were stolen early on, the most valuable being a large ladder. For some reason, a long metal bar used for measuring was also taken, even though it would be of little use to anyone. By far the most unusual thing that disappeared was a stone hearth that had been uncovered on the eastern edge of the site. The hearth was discovered during excavation of a test unit along a fence on the eastern border of the site. Long before the level of the top of the hearth was reached, a distinct circular area of carbon staining was encountered. Eventually, a small but well-constructed stone hearth was uncovered. Several charcoal samples were taken from between and beneath the hearth stones. Radiocarbon assays on one of the samples established an age range of between A.D. 1285 and 1405 for the charred wood, a time which postdates by several centuries that of the rancheria. Nonetheless, the arrow points around this hearth were of the Scallorn type. It appears that this hearth represents a very late occupation by Austin phase people. Because the hearth was so well preserved, we carefully reburied it for later archeomagnetic studies which would help us understand how it was used. Several months later, we reexcavated the unit only to find that the hearth was gone—no trace of it could be seen. We can only presume that someone dug it up thinking something valuable was buried beneath it; when nothing was found, the rocks must have been tossed away and the pit reburied to hide the vandalism. Because the hearth had vanished, we were forced to select another hearth feature for archeomagnetic studies. We chose another small hearth already uncovered near House 1. Small cores were removed from the rocks and taken to the Geology Department at the University of Texas in Austin for testing of the magnetic properties of the samples. Archeomagnetic tests can estimate the temperature at which the rocks were heated and if the rocks were moved after they cooled. The stones in this hearth had been heated to around 300 degrees C (600 degrees F.), a typical temperature for these kinds of features, and they had lain undisturbed during the many centuries since it had been used. |

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||