Clay

Clay occurs in a great many places across the Plateaus and Canyonlands region and is easily accessible in the banks of rivers, including the Colorado, Pedernales, San Saba, as well as smaller streams on the Edwards Plateau. The clays found in the region vary considerably in mineralogy, color, purity, and texture, and thus some are much better suited to making pottery than others. Native peoples used clay in several ways, from pottery vessels and pipes to a sealant (daub) for long-term shelters. Compared to those in other areas, however, such as the Caddo in the East Texas Piney Woods, the prehistoric peoples of this region took up pottery making relatively late, in the latter part of the Late Prehistoric period (Toyah interval; circa A.D. 1300).

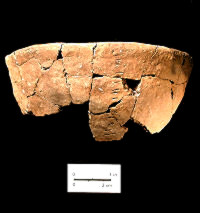

Typically, Toyah potters incorporated crushed animal bone (bison, deer), and less frequently quartz sand or grog (crushed pottery), as tempering agents into the clay and water paste. They then formed the clay into various shapes to make ollas (water jugs), jars, bowls, or other containers which were then dried and fired. Temper is added to clay to improve its workability, drying characteristics, and firing abilities; water is added to increase plasticity. The bison- and deer-hunting Toyah people would have had quantities of bone available to add to clay. The pottery was finished nicely (smoothed and polished) and then fired in open fires at relatively low temperatures. The resulting earthenware pottery was well made and quite serviceable, but relatively fragile and easily broken compared to kiln-made pottery.

The addition of pottery to the native tool kit must have been significant. Although a great deal of aboriginal cooking involved use of small hearths, earth ovens, and flat stone griddles, clay pots would have been extremely useful for cooking stew-like meals and also for hauling and storing water, and storing food stuffs such as seeds and nuts. In bison butchering camps, clay cooking pots would have enabled more efficient “bone-greasing,” the process of boiling animal bones to extract the valuable fatty oils.

Remains of pottery vessels have been found at Toyah interval sites across the Plateaus and Canyonlands. Recognized as well-made, bone-tempered, thin-walled and typically undecorated, the pottery type has been dubbed “ Leon Plain” by archeologists. Usually, a mere handful of sherds are recovered, but in some cases, hundreds of sherds have been found in one site and vessels can be partially restored. Many sherds that are of apparent Leon Plain type were, in fact, decorated with engraved or incised lines. Other sherds bore traces of a red slip sometimes called Fugitive Red Slip. The red pigment coating is thought to contain the iron mineral, hematite, and doesn't preserve well. It was probably to decorate the so-called Leon Plain pottery much more often than is realized. Brushed sherds with sandy paste have also been found in many Toyah contexts, as well as remains of Caddo vessels, either carried in or traded in to the region.

Native peoples also may have used clay to help seal or “weatherproof” their temporary shelters (makeshift houses called huts or wickiups), in what is termed “wattle and daub” construction. Wattle—sticks, branches, or reed stalks—were woven together to make a frame which was then covered with mud or clay “daub” to seal the many cracks. Among historic groups, such as the Apache, the finished structure had the appearance of a basket turned upside down.

Although definitive remains of prehistoric shelters have rarely been documented in the region, pieces of clay have been recovered that may have been daub. This material typically does not preserve well unless the structure was burned. At sites such as Wilson-Leonard in Williamson County, archeologists found a few fragments of burned clay or mud bearing the imprints ofsticks or reeds and we infer that domestic structures were regularly built throughout prehistoric times.

![]()