The Visionary La Salle

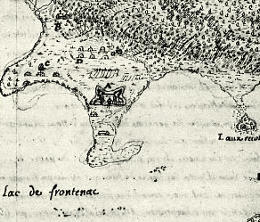

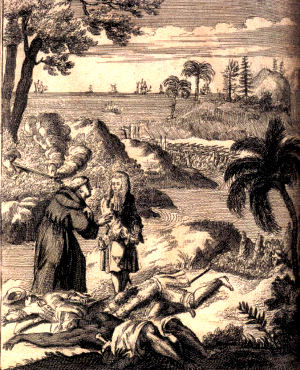

Artist's rendering of the explorer La Salle, shown looking at an early French map of North America. The map shows three forts built between 1679 and 1680: "Conty fort (or Fort Niagra, near Niagara Falls), Miamis Fort (south of Lake Michigan), and Crèvecour fort (left bank of the Illinois River). The Mississippi River (or Colbert) is only shown upstream of its confluence with the Ohio. Map, Carte de l'Amerique Septentrionale, by Claude Bernou, edited 1681, courtesy Wikipedia. See full map |

|

|

|

|

Still, La Salle made significant gains in Canada. On a voyage to France in 1675, he obtained a royal grant to a post on the north shore of Lake Ontario. The new post, named Fort Frontenac, was but a stepping stone to his real ambition. He sailed again for France in 1677 to win a grant for the right to discover (at his own expense) “the western parts of New France; to establish forts wherever he deems necessary”; and to reap the commercial benefits. Within a few years, La Salle built a fort above Niagara Falls and constructed the first sailing vessel (the Griffon) to ply the Upper Great Lakes. The Griffon was a key element of his plan; she would convey him to the lower end of Lake Michigan. From there, by canoe and the necessary portages, he would reach the Illinois River to build a fort and a new vessel for descending the Mississippi. Scarcely begun, the plan began to unravel. The Griffon, carrying a cargo of furs on which La Salle depended to pay his creditors, was lost on the way back to Niagara. The second vessel lay unfinished, as workers deserted. Forced to begin anew, La Salle, with 23 Frenchmen and 31 Mohegan and Abnaki Indians, traveling by canoe, descended the Illinois River to the Mississippi and then turned southward to the Mississippi’s mouth. On April 6 and 7, 1682, La Salle and his men explored three of the river’s eastern outlet channels. Two days later, on a spot of dry land three leagues upstream, he planted the arms of France and claimed for Louis XIV the entire Mississippi drainage. Then began the long journey back up the river, hastened by a lack of provisions and threatened by the hostile Qunipissa and Koroa Indians. La Salle himself fell violently ill along the way. As time would tell, the discovery had its confusing aspects. What he saw on the ground, La Salle realized, did not fit the maps. The discrepancies portended dire results for his effort to find the mouth of his river from the sea. Eager as he was to return to France to report his discovery, La Salle encountered delays. He finally sailed for France, arriving near the end of 1683 to seek support for his voyage to the Gulf of Mexico. From the king of France, he received the grant of the royal ship Belle, a light frigate, with the 36-gun warship Joly assigned as escort. At his own expense, La Salle leased the 180-ton cargo vessel Aimable to carry supplies, then added the Saint François to carry supplies and trade goods as far as Saint-Domingue (Haiti). With France at war with Spain, La Salle's plan was to establish a French base within striking distance of Spanish settlements and silver mines in Mexico. Some maps of the period—all hypothetical—showed the Mississippi River, or Río del Espíritu Santo, discharging into the Gulf near the Texas coastal bend. Without means of taking longitude, La Salle had been unable to determine at what point on the east-west coast his river was found. The faulty maps were his only clue. Thus, his voyage was doomed to failure at its inception. The four ships sailed from La Rochelle, France, on July 24, 1684. Bad omens seemed to stalk the voyage from its inception. An accident aboard Le Joly forced a return to Rochefort for repairs, delaying final departure from France for another week. Dissension among the crew was followed by the loss of the Saint-François to Spanish raiders on the approach to Saint-Domingue, then the defection of several men to a pirate fleet at Petit Goâve. Near Cuba’s western tip, a night-time squall caused the ships to drag anchor and crash together in a mass of tangled rigging. From that point, La Salle set a course for the far end of the Gulf of Mexico, where the maps indicated the mouth of the Mississippi would be found. Navigation was precise but, on arrival there, La Salle could see nothing he recognized. After a month of uncertainty, he began landing the people on Matagorda Island on the Texas coast. Then came the series of misfortunes that ultimately spelled the ruin of his enterprise. His supply ship, Aimable, wrecked while trying to enter Matagorda Bay. Still convinced that the Mississippi was near, he sent the warship, Joly, back to France. With people dying daily, La Salle put the survivors on a 50-mile march up the bay to the site he had chosen on Garcitas Creek, which he called Rivière aux Boeufs for the many buffalo. Never intended as a permanent settlement, this wilderness outpost, known in history as ”Fort Saint Louis,” was meant to be a temporary encampment until La Salle found the main stem of the Mississippi. The means to accomplish his search was to have been his last remaining ship, the little frigate Belle, which he loaded with supplies and weaponry for establishing a post on his elusive river. Then the Belle, too, was lost, running aground on a sandbar during a fierce storm. The people, huddled in their crude camp on the Rivière aux Boeufs, were stranded. La Salle took seventeen men on an eastward march, hoping to find the Mississippi and follow it to his Illinois post—the real Fort Saint Louis—and to travel onward to Canada to seek relief for his meager colony. Had the people waiting in their miserable settlement on the Texas coast received any word at all from the marchers, they would have learned that their leader was dead, the victim of a conspiracy among his disenchanted followers. Although his life was cut short, La Salle’s vision and accomplishments were critical in the shaping of North America. He explored the Great Lakes region and Ohio and Mississippi valleys, blazing a trail to the mouth of the Mississippi on the Gulf shore in 1682. In the name of France, he laid claim to this vast territory, equivalent to roughly one-third of today’s United States, naming it La Louisiane in honor of the French monarch, Louis IV. In 1803, the United States was to acquire much of that land from France in the Louisiana Purchase.

|

|