Distinctive potsherds such as these

fragments of Late Caddo pottery from the A.C. Saunders

site allow archeologists to estimate the date of Caddo

settlements. TARL archives. Click to see full image.

|

Map showing Native America as perceived

by the French in the early 18th century. This was one

of the first reasonably accurate depictions of the Mississippi

and its tributaries including the Red (Rogue) River.

The locations of Cadohadacho (Cadodaquios), Hasinai

(Les Cenis), and Natchitoches are shown. From Carte

de la Louisiana et du Cours du Mississipi, by Guillaume

Delisle, 1718.

|

|

Over 150 generations of Caddo people have lived

and died since the time more than 3,000 years ago (perhaps

much more) when the ancestors of the Caddo split from the

ancestors of the Northern Caddoan groups (see Caddoan

Languages and Peoples section). Over this long span of

human history, Caddo societies have changed in all kinds of

ways, some of them fundamental. Today we have only an inkling

of most of these changes.

Archeologists find evidence of only certain

kinds of specific events, such as the debris lfet behind from a multi-year settlement, the burning of a house or

the burial of an individual, that leave obvious traces. Most

ordinary events and even those that must have been extraordinary

like victory celebrations, visits by the leaders of distant

groups, and the destruction of a village by a tornado, leave

few traces that an archeologist can recognize. Similarly,

most individuals are invisible in the archeological record.

The only individuals who stand apart in prehistory are those

whose burials we find. Archeologists can recognize patterns

and detect trends through time, but without written or remembered

history to guide us, our view of prehistory is very broad—sort

of like flipping through a history book and seeing only the

chapter titles and a few pictures.

To cope with uncertainty and information gaps,

archeologists construct chronologies (timelines) such as the

one presented below. While such a linear concept of time is

useful to scientists and historians, it would have been foreign

to the ancient Caddo. In most traditional Native American

societies, time was perceived as cyclical and reoccurring.

It was measured and marked by moons, seasons, generations,

and transforming events such as massive floods, celebrated

victories, the founding of a new village, or the death of

a charismatic leader.

However, knowledge of most of the transforming

events in Caddo history has been lost, leaving us with a mix

of faint surviving memories, dance and song tradition, a precious

few detailed early written accounts, and an ever-growing mass

of archeological data from hundreds of archeological sites

linked to the Caddo. This latter may sound impressive, but

most such archeological sites are places where fragments of

Caddo-style pottery have been found on the surface and little

investigation has been carried out. Even with the relatively

few sites that have seen extensive archeological research,

it is often difficult to determine precisely when the sites

were occupied without considerable research effort. Dating is almost always an exercise in approximation

in archeology. Even the radiocarbon dating technique yields

only statistical estimates with decades-long standard error

ranges, rather than precise dates.

Our knowledge of the later history of the Caddo,

after Europeans arrived and began recording information, is

much fuller, but still very incomplete. Europeans only wrote

about what they happened to see or learn that interested or

concerned them. And they always saw the Caddo through the

eyes of strangers in a strange land. As we move toward the

present, our view of history becomes sharper and sharper as

we listen to Caddo voices and compare what they say to what

various officials, travelers, and neighbors wrote. Maps, paintings,

photographs, and voice recordings all add critical knowledge.

With these caveats in mind, we present a culture

history timeline that summarizes some of the major changes

through time. In this chart you will notice that the earlier

periods are longer and are often rounded off into centuries

or even thousands of years. This reflects the lack of precision

of our dating methods. Note also that some of the periods

shown below overlap with one another. This is because time

periods are abstract approximations that cut up time into

neat little blocks out of convenience; in reality things do not

always occur in an orderly linear succession or occur simultaneously

from place to place. Even today in the Digital era, there

are still millions of people across the world that do not

have electricity or running water, technological advances

that most of us take for granted. This example reminds us

that technological and cultural changes typically take decades

or centuries to spread, even today.

|

The remains of this burned structure

represent a specific event, the ritual destruction of

a small temple followed by the intentional burial of

the remains with a new layer of earth. Two successive

temples, both burned and buried, were found within and

beneath a small Late Caddo mound at the Harroun site

in Upshur County, Texas. TARL archives.

|

| As

we move toward the present, our view of history becomes

sharper and sharper as we listen to Caddo voices and compare

what they say to what various officials, travelers, and

neighbors wrote. |

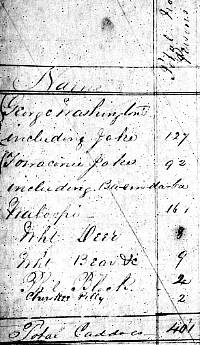

The 1873 census records a total of

401 Caddos, including 116 men, 139 women, 86 boys, and

60 girls as well as 2214 horses, 1032 cows, and 1293

hogs. Courtesy Cecile Carter.

|

|