Wind Canyon

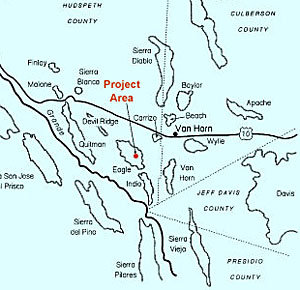

The Wind Canyon site (41HZ119) is located on an alluvial fan deposit in Wind Canyon on the east slope of the Eagle Mountains, approximately 25 kilometers (16 miles) southwest of Van Horn. It was visited repeatedly over a period of 1150 years by small groups of people for the primary purpose of harvesting and processing lechuguilla in earth ovens.

Wind Canyon was first recorded in 1979 during a reconnaissance of the Eagle Mountains conducted as part of the Natural Areas Survey Project, sponsored by the University of Texas at Austin. Surface survey was conducted at the site by Batcho and Kauffman Associates in 1992 as part of a larger survey of areas that were to be affected by construction of the Federal Aviation Administration’s Air Route Surveillance Radar installation. The first subsurface investigations at Wind Canyon were carried out later that year when archeologist Margaret Howard of Prewitt and Associates, Inc., tested the site to determine whether it was eligible for listing on the National Register of Historic Places, pending construction of an access road to the installation that would cross much of it. The site was declared eligible for listing on the register in 1993, prompting Prewitt and Associates, Inc. to conduct mitigation-level excavations shortly thereafter.

Through radiocarbon assays and ceramic and projectile point type cross-dating, Wind Canyon has been dated to the period between 800 B.C. and A.D. 1480, with the most intensive use of the site occurring between A.D. 1000 and 1480. From 800 B.C. until A.D. 340, campers at the site used nonspecialized hearths for a variety of tasks. Around A.D. 340, they began to use earth ovens for the primary purpose of processing lechuguilla.

Earth ovens were used by the native peoples of Texas to cook starchy plant foods that must be slowly baked for hours or days before they become edible. They were constructed by digging a pit and building a fire at the bottom to heat rocks. Once the fire burned down, the heated rocks were arranged in a circular heating bed and plant food was wrapped in grass and placed on top of it, then covered with earth. After the necessary cooking time had elapsed, the oven was opened and the plant food was removed. Earth ovens were reused through the years, but the rocks were often broken in the heating and cooling process and had to be replaced. The broken rocks were thrown out, creating a scatter of burned rocks around the oven known as a burned rock midden. Burned rock middens formed through dozens to hundreds of usage events over hundreds to thousands of years, and often became exceedingly large. For a more detailed explanation of earth ovens and burned rock middens, see the Camp Bowie exhibit.

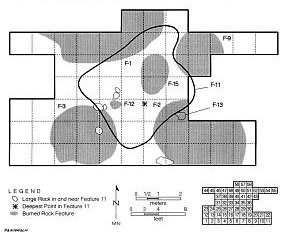

Three burned rock middens were identified at Wind Canyon. The first began to form at A.D. 340 and continued to grow gradually until the site was abandoned in A.D. 1480. The second began to form at A.D. 680 and grew gradually until A.D. 1430. The third began to form at A.D. 1000 and grew very rapidly until A.D. 1430, making it the largest of the three. Though these middens overlap in time, their earth ovens would not have been used simultaneously during a single site visit. A new earth oven was likely constructed once the burned rock midden around an existing oven became so steep that rocks began to fall into the oven during clean-out episodes, impairing the use of that oven. The new oven would become the primary oven, but the old one may have been reused occasionally.

The people of Wind Canyon used earth ovens primarily to process lechuguilla plants in the late spring, between April and June. Episodes of lechuguilla processing were brief, perhaps only seven days long, and processing parties were probably small. They gathered mature lechuguilla plants, removed their leaves from their bases, and baked the bases for 48 hours. After removing the bases from the earth oven, they pounded the juice out of them with manos and metates and caught it in ceramic vessels. They then formed the bases into patties and dried them out. These lechuguilla cakes could be stored for several months and may have been an important winter food. After an episode of lechuguilla processing, the area around Wind Canyon would have needed 8 to 20 years to recover before it could produce enough mature lechuguilla plants for another harvest.

The secondary purpose of the earth ovens was to bake nuts, seeds, and fruits that bloom in the late summer and early fall, after the summer rains. These include piñon nuts, the seeds of goosefoot, purslane, and carpetweed, and the fruits of hedgehog cactus, prickly pear, yucca, and juniper. This activity may have taken place annually at the site.

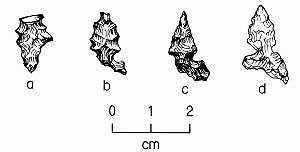

Though lechuguilla processing was the primary activity performed by the people of Wind Canyon, they also engaged in hunting and meat processing. The large number of projectile points recovered from the site suggests that hunting was an important activity for the campers, particularly before they began to construct earth ovens. They preyed upon deer, rabbits, hares, squirrels, and possibly birds. Rabbits, hares, and squirrels were processed and consumed at the site, but deer were only partially processed at the site, then transported offsite to locations where a greater number of people could share in their consumption.

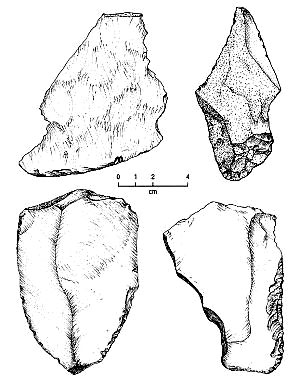

The people of Wind Canyon made chipped-stone tools from syenite, trachyte, and chert. Syenite is available in the vicinity of the site and was used to manufacture expedient tools. Trachyte was brought to the site from the Van Horn Mountains as large flake blanks that were used as knives and eventually reworked into bifaces. Chert was brought to the site from further away as finished projectile points that were resharpened there. Wind Canyon’s chipped-stone tool assemblage is geared towards lechuguilla processing. It is largely made up of expedient unifaces and cobble tools that would have been used to remove leaves from the lechuguilla bases before baking. Wood working is also evidenced at the site by the presence of gouges that would have been used to manufacture or repair wooden artifacts. It is not known what these wooden artifacts were.

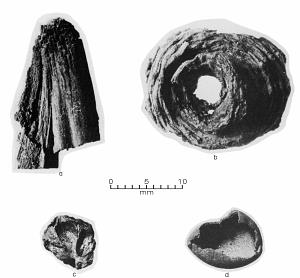

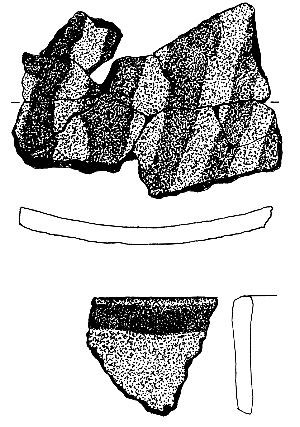

Most of the ceramics from Wind Canyon were manufactured in the region. Their styles include El Paso Brown, Jornada Brown, Micaceous Brown, and El Paso Polychrome. Intrusive Chihuahuan Polychrome and Chupadero Black-on-White were also recovered from the site, suggesting that the people of Wind Canyon participated in a regional trade network with the people of northern Mexico and central New Mexico. Obsidian was sourced to the Jemez Mountains of northern New Mexico, and probably was obtained from gravels along the Rio Grande.

Wind Canyon is just one of many sites visited during the seasonal rounds of a mobile hunter-gatherer people. Though it may have been visited annually to process nuts, seeds and fruits, the site was probably used only once every 8 to 20 years to process lechuguilla. Fine-grained lithic material and a single mussel shell recovered from the site suggest that the range of its residents was fairly large, stretching south to the Rio Grande and east to the Van Horn Mountains. What they did for the rest of the year is not clear, because of the lack of intensively surveyed and excavated sites in this region.

Contributed by Carly Whelan based on a report by Margaret Howard and others cited below.

Sources

Hines, Margaret H., Steve A. Tomka, and Karl W. Kibler

1994 Data Recovery Excavations at the Wind Canyon Site, 41HZ119, Hudspeth County, Texas. Reports of Investigations 99, Prewitt and Associates, Inc., Austin.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|