Alex Krieger in a 1939 photograph

taken soon after he took over the WPA archeological

laboratory in Austin. TARL archives.

Click images to enlarge

|

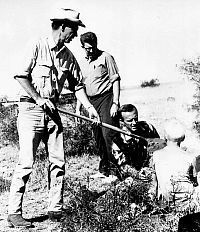

Krieger visits Coetas Creek 55 during

a brief fact-finding trip to the Texas Panhandle in

July, 1945. From left to right: Floyd Studer, Alex Krieger,

Clarence Webb, and Clarence Webb, Jr. Studer obviously

led the field tour. The elder Webb, a medical doctor

from Shreveport, Louisiana, was a first-class amateur

archeologist and one of Krieger's collaborators. TARL

archives. |

Fragments of distinctive pottery

from the Southwest are occasionally found at Antelope

Creek sites. They are thought to represent trade pieces

and provide evidence of contact between the two cultural

areas. Such finds yielded the first accurate estimates

of the age of Antelope Creek sites. PPHM collections,

photo by Steve Black. |

Antelope Creek Ruin 22 during the

WPA excavations, date unknown. PPHS archives. |

Cover of a 2002 book by Lee Lyman

and Michael O’Brien (University of Alabama Press).

McKern's classification system relied on trait-by-trait

comparisons, an simplistic approach that seemed to make

sense in the 1930s and 1940s before radiocabon dating

was available. |

Krieger's

Summary of Antelope Creek

The first area investigated was the northern

Panhandle of Texas. Here we found a most interesting

situation regarding masonry structures in the narrow

corridor of the Canadian Valley. After reviewing and

drawing together various sources of information, an

Antelope Creek Focus was defined and related materials

traced through other parts of the Panhandle, principally

on its eastern side, and in northeastern New Mexico,

southeastern Colorado, and the Oklahoma Panhandle. ...

read

more>> |

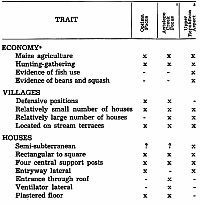

This comparative trait list from

Watson’s 1950 article on the Optima focus is typical

of the culture historical approach taken by many American

archeologists of the day. Such comparisons were used

to judge the relationships among sites and cultures.

Such a” check-list” approach is considered

too simplistic today. From the Bulletin of the

Texas Archeological and Paleontological Society,

Volume 21, courtesy of the TAS. |

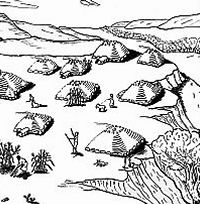

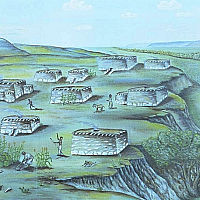

Tale of Two Pictures, Part

1: This undated and unsigned drawing comes

from the files of the Sam Noble Oklahoma Museum of Natural

History, where the Stamper site collections are housed.

Archeological sleuth Chris Lintz surmises that it depicts

the Stamper site as its 1933-1934 excavator, C. Stuart

Johnston, envisioned it during the period he was working

at the site. Note that the buildings have very low walls

and hipped, thatched roofs with low, extended entranceways.

Compare drawing to Johnston's 1935 painting of the same

scene (Part 2). |

Jack Hughes working with volunteers

at a dig on an Antelope Creek site on the Marsh Ranch

in the late 1960s. Photo by Rolla Shaller. |

These notebooks contain much of Jack

Hughes’ documentary legacy. Although Hughes did

not publish most of his fieldwork, he was a faithful

and organized note taker. He was in the habit of typing

up his hand-written and mentally noted observations

as soon as he returned from the field organized as daily

entries in field-journal style. Today Hughes notebooks

are part of the archives of the Panhandle-Plains Historical

Society at the Panhandle-Plains Historical Museum in

Canyon. Photo by Rolla Shaller. |

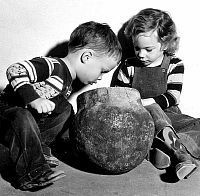

David and Martha Hughes inspect a

Borger Cordmarked jar at the Panhandle-Plains Historical

Museum where their father was curator of archeology

and paleontology. Jack Hughes often took his family

along on weekend digs and it was perhaps inevitable

that son David would become an archeologist (see Buried

City exhibit). Photo taken in late 1950s. PPHS archives.

|

| |

The Medford Ranch site under excavation

in 1962 by archeologists from the Texas Archeological

Salvage Project at the University of Texas at Austin

under the direction of Lathel Duffield. This work exposed

the foundations of two structures, a typical rectangular

Antelope Creek house with an extended extranceway and

a two-room structure. TARL archives. |

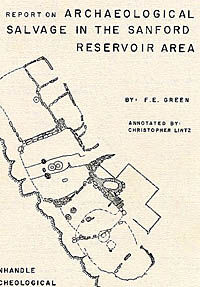

Cover of Earl Green’s report

on the Footprint site that he excavated over twenty

years earlier. The Footprint site was (and is) remarkable

because one of the three isolated houses there was the

scene of a grisly sequence of violence that some experts

believe may represent a massacre of a small community

followed by a revenge killing of ten individuals. While

the details of what transpired will never be known,

the site is one of a growing number of Plains Village

sites in the Texas Panhandle with clear evidence of

conflict. |

|

World War II brought about a virtual halt to archeological fieldwork in the Texas Panhandle as elsewhere in the United States, but there was still one big payoff yet to come from the New Deal archeological projects. In 1946, just after the war ended, Alex D. Krieger published a ground-breaking study entitled Culture Complexes and Chronology in Northern Texas that included a formal definition and thorough synthesis of what he termed the Antelope Creek focus. Krieger’s study was the first concerted effort to make sense of the various pottery-making and corn-growing prehistoric cultures in the Southern Plains and the adjacent prairies and timbers across northern Texas. His ultimate scholarly goal was to link the relatively well-established chronology (dating framework) of the Puebloan Southwest to the poorly dated Mississippian region west of the Mississippi River (i.e., the Caddo area of east Texas and adjacent states).

At the time Krieger was a research scientist at the University of Texas at Austin where he had been hired in 1939 to supervise the state’s largest WPA archeological laboratory. In contrast to most earlier archeologists, Krieger had the scholarly training to grasp the complexity of ancient cultural history and the discipline to carefully distinguish between observation and interpretation, assertion and inference, fact and opinion. While most archeologists of the day were drawn to digging, Krieger was primarily a laboratory-based analyst and writer. His 1946 study earned him the 1948 Viking Fund Medal in archeology, one of the highest honors in the field. His 1949 report on the George C. Davis site, a major Early Caddo mound site in east Texas (co-authored with WPA excavator Perry Newell), is still considered one of the classic archeological studies of all time.

Krieger understood that systematic frameworks and consistent sets of terms were needed for communication, comparison, and interpretation. But he also knew that such concepts were merely trial approximations that later researchers would improve upon or reject entirely. Krieger went to great lengths to carefully point out the limitations of the interpretive schemes he used as well as the many information gaps and uncertainties within the field data upon which his ideas were based.

In 1945, when Krieger turned his attention to the archeology of the Texas Panhandle, he approached the task in his typically methodical way. He read everything published on the topic and studied as many artifact collections as he could get his hands on. His first-hand experience in the area was limited to brief visits to some of the major Antelope Creek sites as well as the Panhandle-Plains Historical Museum. Floyd Studer was Krieger's major informant, but he also examined the extensive collections amassed by several landowners in strategic parts of the region. What mattered most to Krieger was solid evidence and he was perfectly willing to consult with collectors and amateur archeologists as well as his professional colleagues

To attempt to classify

Antelope Creek Focus as either a Plains or Puebloan culture

is infeasible, for it was clearly a combination of both. …

One can hardly escape the impression that the peoples of this

focus were Plains agriculturalists who pushed southward from

one valley to another as far as eastern New Mexico. Here contact

was established with Puebloans who were expanding their territories

at the same time. … Contact with Puebloans, however,

explains little. If Puebloan architectural elements were established

in the Canadian Valley of Texas, should there not be more

Puebloan pottery in the ruins than the few dozen pieces found

to date? … The situation clearly points to selective

borrowing and acculturation between the two peoples.

-- Krieger 1946, p. 73

In the first part of the 1946 study, Krieger critically reviewed what was known about Plains Village sites in the Texas Panhandle and adjacent areas of western Oklahoma, northeastern New Mexico, southeastern Colorado, and southeastern Kansas. He masterfully summarized the important points made by earlier researchers and tactfully pointed out key assertions and conclusions others had reached without presenting solid evidence. For instance, Krieger expressed reservations about Studer’s claim that Antelope Creek houses had flat roofs. “Show me the data,” seems to have been Krieger's mantra. The review is followed by a synthesis of the Antelope Creek focus and considerations of its dating and relationships to other cultures. (Download Krieger’s 1946 review and synthesis in PDF format.)

Krieger proposed the Antelope Creek focus concept to replace the loosely applied labels that others had used including the Texas Panhandle culture, the Panhandle phase, the Panhandle culture, the Texas Panhandle Pueblo culture, the Canadian culture, the Panhandle-Canadian culture, and the Slab-House culture. In doing so he adapted a relatively new classification scheme called the Midwestern taxonomic method or McKern system after its chief proponent, W. C. McKern. This hierarchical scheme was conceived of as analogous to the biological classification system created by the renown 18th-century Swedish naturalist, Carolus Linnaeus. In place of the Linnaean family>genus>species, were McKern’s pattern>phase>aspect>focus (broadest to narrowest groupings). But unlike biological species, archeological site assemblages (groups of artifacts consistently found together) were poorly suited to be classified using such a scheme.

Site assemblages were created by groups of people (cultures, tribes, bands, etc.) who were biologically and culturally interrelated in complex ways and historically connected through time and across geographical space. McKern’s classification system relied on trait-by-trait comparisons and ignored time and space, the two most important variables in reconstructing culture history, how cultures changed and interacted through time. In fairness, when McKern proposed his system in the 1930s, radiocarbon dating hadn’t been invented and the age of most archeological sites in the Midwest was poorly known, so it seemed natural to define cultural relationships based on observed similarities. Interested readers can find web pages and entire books devoted to discussing the McKern system and why it failed.

Krieger realized the chief limitations of the McKern system and tried to adapt it by starting at the narrowest and easiest-to-define grouping, the focus. He thought McKern proponents erred in trying to start with the broadest level “pattern” and then defining ever-narrower groupings, a process he felt was bound to fail. Krieger believed, however, that the reverse strategy might work–start with the narrow groupings we can be most certain of, like Antelope Creek, and then attempt to work out more abstract, higher-level cultural relationships. He also saw no reason that the narrower groupings could not be limited to geographical clusters of archeological assemblages and sites dating to limited periods of time. His approach was eminently sensible.

Krieger conceived of the Antelope Creek focus as a relatively consistent set of material traits (artifacts, architecture, food refuse, etc.) occurring at a series of closely related archeological sites (Plains villages) within a restricted area (the northern Texas Panhandle and nearby). The material culture, he thought, was the product of a culture of closely related “Plains agriculturalists” who had lived in the area for a relatively brief period of time, roughly A.D. 1300-1450. He designated Antelope Creek 22 and Alibates Creek 28, the two largest and best-known sites investigated by the WPA, as the “type” sites said to exemplify the Antelope Creek focus.

In order to allow for the probability that other, analogous foci (plural of focus) would ultimately be recognized in the same general vicinity, Krieger proposed the Panhandle aspect as a broader grouping, but did not define it in the 1946 publication. He and his colleagues later provided a definition of the Panhandle aspect in the 1954 Handbook. Although archeologists continued to use these concepts for decades, most professional archeologists active today consider the term "Panhandle aspect" to be outdated. Improved versions of the Midwestern taxonomic method are still in use by some archeologists, although they no longer resemble McKern’s original system. Antelope Creek, however, lives on today as a “phase” (not the same as a McKern phase and still different from Sayle's phase) or, more simply put, an archeological culture.

While some of Krieger’s Antelope Creek ideas and inferences have been refined or rejected by later researchers, much of what he figured out about Plains Village life in the Texas Panhandle is remarkably close to the way we see it today.

Stamper site and the Optima focus

During the 1940s and 1950s, few field investigations were undertaken of Antelope Creek sites apart from continued site exploration and documentation by Studer and his successor, Jack Hughes. One significant development was a 1950 article by Virginia Watson on the Stamper site in the Oklahoma Panhandle. Watson, an archeologist whose husband taught anthropology at the University of Oklahoma, analyzed the materials from the Stamper village that had been recovered by Johnston and Carder in the 1930s. Her work was hampered by missing site maps and the disorganized nature of the collections and notes. Nonetheless, she provided the first published account of the site and called attention to the differences between the Stamper architecture and that of the Antelope Creek type sites. The Stamper houses she was aware of were isolated from one another instead of being arranged together in a block like a pueblo. She also observed relatively minor differences in artifacts.

On the basis of these differences, Watson followed Krieger’s lead and defined the Optima focus, which she proposed to be the second grouping within the Panhandle aspect. The Optima focus, she argued, represented a Plains Village culture that was intermediate, geographically and chronologically, between the Upper Republican culture of the Central Plains and Antelope Creek. Although Watson’s Optima concept was used by Oklahoma archeologists for several decades, it never really caught on elsewhere. Subsequent work at other Plains Village sites in western Oklahoma has complicated the picture and called into question many of the inferences upon which the Optima focus was based. The recent (2002-2004) reanalysis of the Stamper site by Chris Lintz has pointed out some of Watson’s misinterpretations due to the incomplete information she had to work with.

Jack Hughes:

Dean of Panhandle Archeology

When Jack T. Hughes arrived in Canyon in 1952 to take over Studer’s position at the PPHM, he ushered in a new era for Panhandle archeology. Hughes was the museum’s first paid curator of archeology and paleontology, but he also taught part-time at West Texas State College (as WTSTC was then known), as had C. Stuart Johnston in the 1930s. Like Johnston, Hughes had training in both geology and anthropology, but didn’t yet have his Ph.D.; he had completed everything but his dissertation in anthropology at Columbia University. Likewise, Hughes was charismatic and quickly became a favorite of students and his colleagues at the museum and the college. Like Studer, Hughes had a penchant for exploration and came to know the Panhandle and the northern Llano Estacado as well as any archeologist probably ever will. But there the similarities with his predecessors stop.

Jack Hughes' first dissertation topic (a pottery analysis) was rejected by his major professor at Columbia, William Duncan Strong. Encouraged to take on a more challenging problem, Hughes decided to try to reconstruct the culture history and prehistory of the Caddoan language family. This required mastering and synthesizing large sets of archeological, historical, ethnological, and linguistic data, a process that took him over a decade worked in around his museum and teaching responsibilities. Upon completion of his Ph.D. in 1968, Hughes became a full time professor at West Texas State University and had a long and successful teaching career in Canyon. In contrast to Studer, he wasn’t possessive about Panhandle archeology; instead, he encouraged hundreds of budding archeologists to try their own hand in it, including well over a dozen professional archeologists who are still active today. By the time he retired from teaching in 1985, Jack Hughes had become a legend in his own time, a man often called the Dean of Panhandle Archeology.

For Hughes, the Antelope Creek villages were only one aspect of Panhandle archeology. He was just as interested, perhaps even more so, in sites representing the earlier Woodland, Archaic, and Paleoindian cultures. And although he visited and recorded hundreds of Plains villages and dug at dozens of them, he never wrote formal reports on most of the work.

Regardless, Hughes did direct important excavations at various Antelope Creek sites in the Texas Panhandle. Most of the work was accomplished with little or no funding and a heavy reliance on student and avocational volunteers. Hughes preferred the term “Panhandle aspect” instead of "Antelope Creek focus," perhaps because he recognized a great deal more variation among the Plains Villager sites he investigated than Krieger’s definition of the Antelope Creek focus would accommodate. Among these sites, Hughes excavated the Marsh sites with the West Texas State University Anthropology Society; the Roper, Pickett, and Cottonwood Creek sites with the Norpan (Northern Panhandle) Archaeological Society; the Zollars site with the Panhandle Archeological Society; and Sanford Ruin with the Panhandle-Plains Historical Museum. Many of these sites fell within an area that is today periodically inundated by Lake Meredith.

Archeology of Sanford Reservoir

The federal government’s decision in 1960 to dam the Canadian River near the town of Sanford in Hutchinson County had a far-reaching effect on both the archeology and the understanding of Antelope Creek villagers. The impoundment, originally called Sanford Reservoir and later renamed Lake Meredith, is located in the middle of the core Antelope Creek region. Sanford Dam was completed in 1965 and the reservoir soon began to fill.

In 1961, archeologists from the Texas Archeological Salvage Project at the University of Texas at Austin began studying the area that would be inundated by the reservoir under contract to the National Park Service. Archeologists W.A. Davis and Bill Harrison had only ten days to survey 46,350 acres of rugged terrain in search of important archeological sites. While a thorough survey by today’s standards would require months of work, Davis and Harrison located and documented 51 sites in the allotted time, a fraction of the sites that must have been present. Today, a survey (inventory) effort would be followed by a testing (evaluation) phase to determine which sites have the best potential to yield important information. But in 1961, there was no time or money for careful inventory or evaluation.

The following year (1962), excavations were undertaken at three Plains Village sites located in areas that would be impacted by the construction of Sanford Dam. Instead of large ruins with contiguous rooms, the Conner, Medford Ranch, and Spring Canyon sites were small sites with several isolated or paired structures that varied considerably in size and construction. Lathel Duffield’s 1962 report on the work pointed out that the architecture of these sites didn’t fit that of the Antelope Creek focus defined by Krieger, perhaps because earlier archeologists had only investigated the larger sites.

In 1963-1964, F. Earl Green at the Museum of Texas Technical College (now Texas Tech University) excavated six additional sites in the area that would become Lake Meredith. Four of these were Plains Village sites, including the Arrowhead Peak site, a block of 4 or 5 rooms that occupied a defensible position. The other three were open sites with isolated or paired structures. The Footprint site was remarkable because one of the three isolated houses there was the scene of a complex sequence of violence.

Footprint House 1 contained the skeletal remains of at least 32 individuals. Some of the bones were scattered across the house floor, some were found within burial pits dug into the floor and some were found with the post-abandonment fill covering the floor. The most distinctive arrangement was a tight cluster of ten adult skulls found within the fill layer above the floor. Pothunters had dug into one corner of the room, removing some bones and complicating things even further. According to Lintz, later researchers inferred that many of the individuals were massacre victims whose partially dismembered bodies were scattered across the room floor. The house was apparently burned soon after (or during) the massacre event and was abandoned. The skulls are suspected to represent “trophy” heads placed within a pit dug into the burned and abandoned house, perhaps to commemorate the avenging of the earlier massacre. Tellingly, the skeletal features of the skulls do not match those of Antelope Creek people and presumably represent their enemies. These findings underscore the importance of warfare and conflict in Antelope Creek life.

|

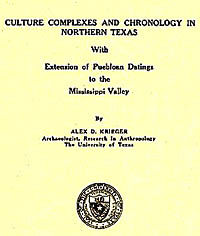

This 1946 ground-breaking study by

Alex D. Krieger was the first concerted effort to make

sense of the various pottery-making and corn-growing

prehistoric cultures in the Southern Plains and the

adjacent prairies and timbers across northern Texas.

As part of that effort, Krieger formally defined the

Antelope Creek focus and synthesized what was then known

about the Plains villages of the Texas Panhandle.

|

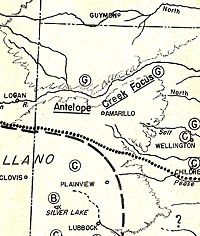

Detail of Krieger's 1946 map showing

the location of the Antelope Creek Focus. The circled

capital letters show the locations where various styles

of distinctive trade pottery had been found.

|

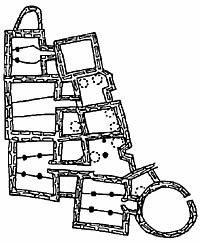

Main room block at Antelope Creek

28. Graphic simplified from WPA plan maps that appear

in Lintz 1986.

|

FAQ: What is Culture History?

For archeologists and anthropologists,

culture history is an analytical approach that seeks

to describe past cultures and the things those cultures

created (“material culture”) through historical

time and across geographical space.

Culture historians begin by ...

read

more>>

|

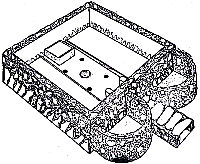

Idealized reconstruction of an Antelope

Creek house published by Krieger, 1946. This drawing

was based on the scale model constructed by WPA workers

for the Panhandle-Plains Historical Museum under Studer's

supervision.

|

This 1950 article by Virginia Watson

on the Stamper site in the Oklahoma Panhandle was the

first substantial publication on the site. Watson concluded

that enough differences existed between Stamper and

Krieger’s Antelope Creek focus to warrant the

definition of a new cultural unit which she named the

Optima focus. Today, the Optima focus is no longer seen

as a valid concept and the Stamper site is thought to

be closely related to, if not part of, the Antelope

Creek culture. From the Bulletin of the Texas

Archeological and Paleontological Society,

Volume 21, courtesy of the TAS.

|

Tale of Two Pictures, Part

2: This 1935 painting by C. Stuart Johnston

hangs in the Panhandle-Plains Historical Museum in Canyon,

Texas. The scene depicts the Stamper site in the Oklahoma

Panhandle, where Johnston had directed excavations in

1933-1934. Note, however, that the buildings are shown

as rectangular, flat-roofed Pueblo-style structures

identical to the Antelope Creek houses envisioned by

Floyd Studer, whose cooperation Johnston depended on at the museum.

|

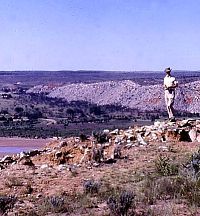

Jack Hughes at the Sanford site,

a small Antelope Creek hamlet perched on the south rim

of the Canadian River Valley. The site was later destroyed

when the dam was built to create Sanford Reservoir (today’s

Lake Meredith). This 1953 photo was taken by Alex Krieger.

TARL archives.

|

Jack Hughes (left), Alex Krieger

(center), and Charles Steen at the Midland site in 1953

soon after a partial human skeleton was found there

in apparent association with Paleoindian artifacts.

Krieger was Hughes’ mentor dating back to the

early 1940s. Photo by Fred Wendorf.

|

Excavations underway in 1957 at the

Roper site by the Norpan Archaeological Society. The

site was selected because it was in the immediate vicinity

of where construction on Sanford Dam would take place

and because it appeared to represent an Antelope Creek

hamlet with its cluster of four circular houses. Volunteers

did the lion’s share of the archeology that was

done in the Canadian River Valley prior to the filling

of Lake Meredith. Photo by Dick Carter, courtesy Chris

Lintz.

|

Lake Meredith inundated dozens of

Antelope Creek sites, only a few of which were carefully

studied prior to the completion of Sanford Dam in 1965.

As a result of federal laws passed soon after the lake

was built, a similar reservoir project today would result

in years of concentrated archeological investigation

to mitigate the loss of information. This photo by Chris

Lintz was taken in the 1980s when the reservoir was

full, a rare occurrence these days.

|

August 1962 excavation scene at the

Conner site. The site consisted of two tiny side-by-side

circular house foundations (each about five feet in

diameter. Both structures had a small trash midden just

outside the apparent doorway, leaving little doubt that

these really were habitations. Bill Harrison, who would

later succeed Jack Hughes as curator at the Panhandle-Plains

Historical Museum, is the shirtless man. TARL archives.

|

|