|

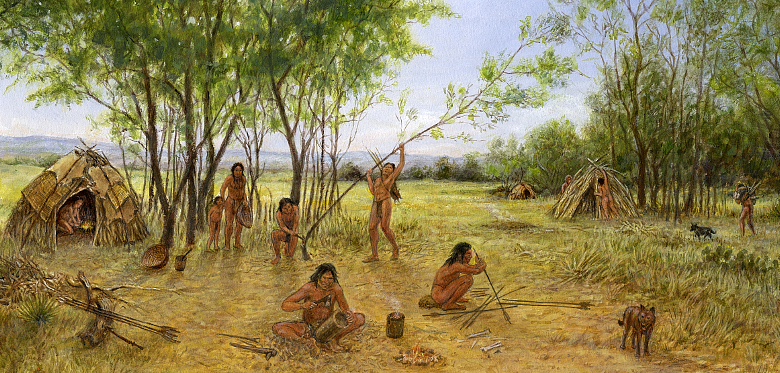

Like the many other prehistoric groups in Texas, the people who made their camps along the banks of the Medina River at the Richard Beene site lived a foraging lifestyle. This lifeway, also known as hunting and gathering, required an intimate knowledge of the environment to be successful. Such knowledge often led native peoples to locate their settlements in strategic locations such as the ecotonal area around the Beene site, within a short distance of a number of different resources in the immediate vicinity as well as in a day's walk or so. The site's ideal location is likely the main reason that people returned over and over again over a period of some 10,000 years.

The people who camped at the Beene site were likely small families or slightly larger family

bands numbering from 10 to 25 people. These larger groups most likely would have consisted of some

combination of grandparents, parents, children, aunts, uncles and cousins. While encamped at the site, individuals or small groups would have traveled as far as 25 miles into the surrounding

countryside to hunt or gather foods.

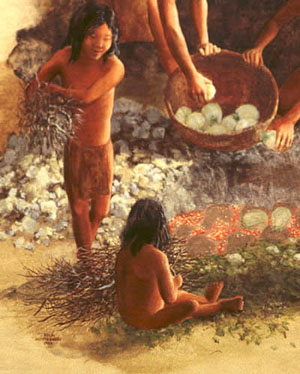

Though the area around the site was and is rich in natural resources, the camps at the site would have been only one stop in a seasonal round that brought groups to different areas at the time of year when resources could be most easily exploited. At the Beene site, there are a number of reasons to think that the groups who camped along the river did so mainly during the winter. Trees growing in the deep soils of the Medina River floodplain would have provided a source of firewood and house-construction material for groups wintering nearby. The large amount of fire-cracked rock and the remains of earth ovens throughout the site attest to the importance of root foods in the diet of these groups. These root foods would have been most important during the winter months, when they were laden with carbohydrates in anticipation of the spring growing season. Spaniard Alvar Nunez Cabeza de Vaca, who passed through southern Texas on his way to Mexico after being shipwrecked near Galveston Island in 1528, attested to the use of root foods by native groups during this season.

Like the root foods, the fire-cracked rock used to bake these root foods in earth ovens was gathered in the immediate vicinity of the site. Outcrops of sandstone bedrock in the Medina River floodplain and on the adjacent terrace provided a ready source of cookstone for constructing earth ovens and hearths with rock heating elements, and the remnants of these cooking facilities were found in every component at the site.

Though bone was typically not well preserved at Beene, the bones that were recovered indicate that white-tailed deer were an important resource for native groups throughout the occupational history of the site. Deer would have been useful not only for their meat but also for their hides and bones, which served as raw material for clothing and tools. The bones of other animals used for food were found at the site, including rabbits and rats.

Hunting of larger animals would have been accomplished using stone-tipped projectiles; these would have been darts or spears during most of the site’s occupational history, with arrows being used only in the very latest portion of prehistory. Most of the stone projectile points were made from materials that, much like the food eaten by the site’s occupants, were found nearby. Floods on the Medina River carried cobbles of Edwards chert from the Edwards Plateau to the area near the Beene site; when the floods abated these cobbles were deposited in gravel bars along the river.

In addition to supplying raw material for stone tools, the Medina River also provided its fair share of food for those camping in the area. The remains of turtles, fish, and river mussels attest to the importance of the river’s resources for the Beene site’s occupants. Mussels seem to have been of particular importance, as their remains are a significant element of every component at the site.

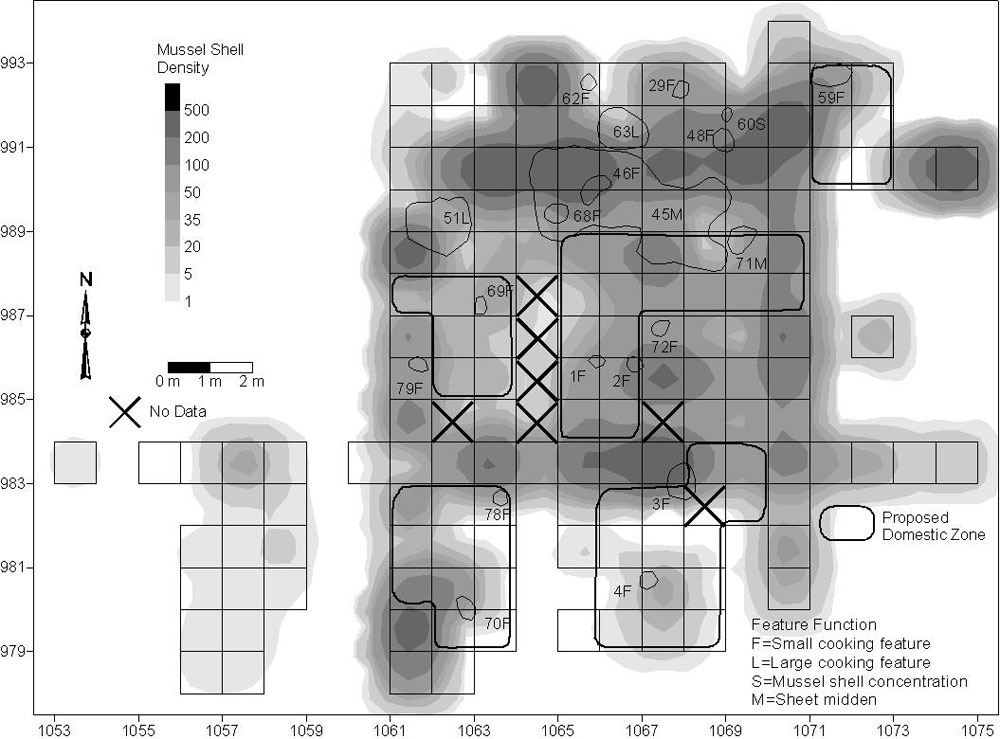

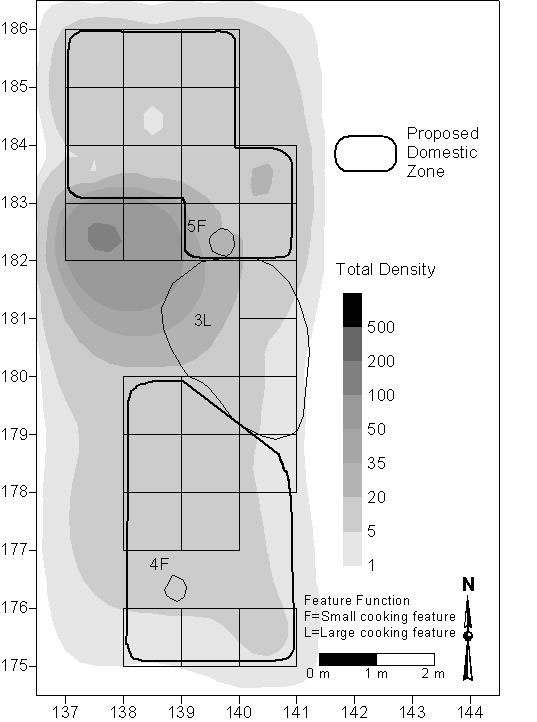

Though there is no direct evidence for the number and kind of houses used by the native peoples who camped at the site, it is generally believed that residential structures were used from the time the first humans set foot on the North American continent. In the absence of preserved structures, archeologists working with the assemblages recovered from the site relied on spatial analysis to suggest the presence and location of residential structures. Spatial analysis uses the patterning of artifacts and features at archeological sites to make assumptions about the kinds of activities that led to those patterns. To look for patterns that suggest domestic areas such as houses or structures, archeologists look for features, especially small hearths, combined with lower frequencies of artifacts due to the repeated house-cleaning. Bone fragments within these domestic areas are expected to be smaller than those in "outside" areas, reflecting the fact that most of the butchering and other processing of the animals would have already taken place in another area.

The structures that most likely would have been used at the Richard Beene site were a type known as a wikiup. These structures would have been supported by bent poles and covered with any number of items including hides, fiber mats, boughs. Early European visitors to Texas, including Cabeza de Vaca and the Frenchman Henri Joutel, documented mat-covered shelters or domed huts among the native groups in south and southeastern Texas. These descriptions suggest that a family of four or five people lived in each hut.

|

A group of Indian people place plant parts in an earth oven to cook.

From painting by Nola Davis, courtesy Texas Parks and Wildlife Department.  |

Modern bulbs of plants that grow in the area near the Richard Beene

site were used as comparative samples to aid in identification of the prehistoric bulbs. From left

are false garlic (Northoscordum bivalve), wild onion (Allium sp.), and eastern camas (Camassia

scilloides). Photo by Phil Dering.  |

This small basin-shaped cooking pit is the type of feature that may

indicate a domestic area such as a wikiup or other residential structure.  |

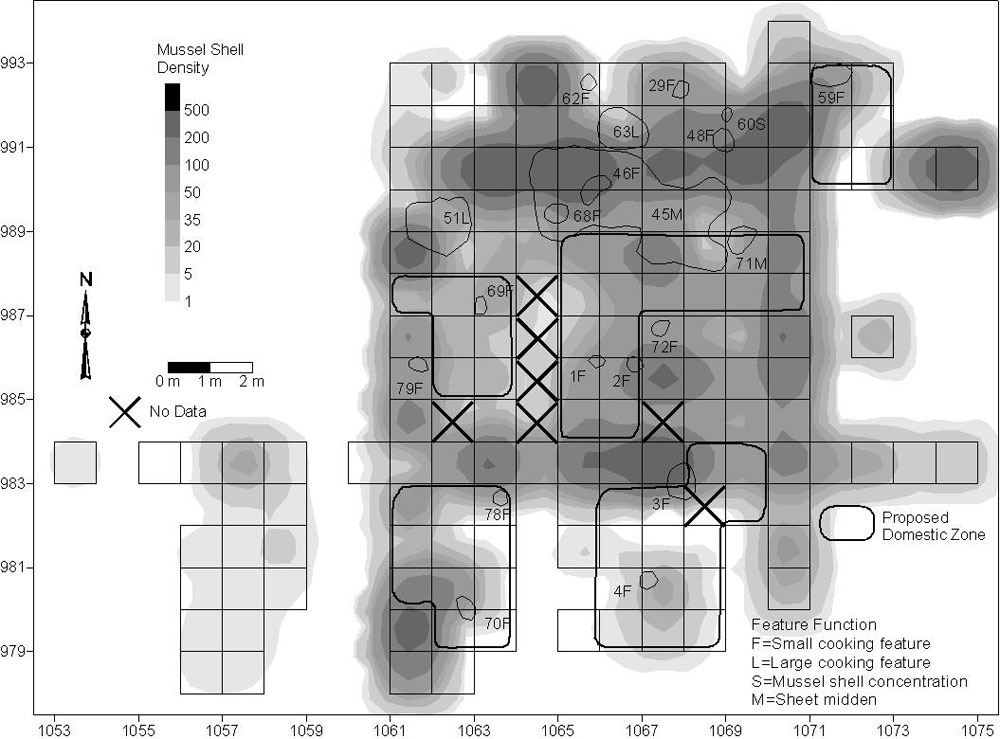

This plot of artifact density (in items per square meter) in a

late Early Archaic component isolated in Block G shows proposed "domestic zones" containing small

cooking features indicative of those found in residential structures. Enlarge to see detail.  |

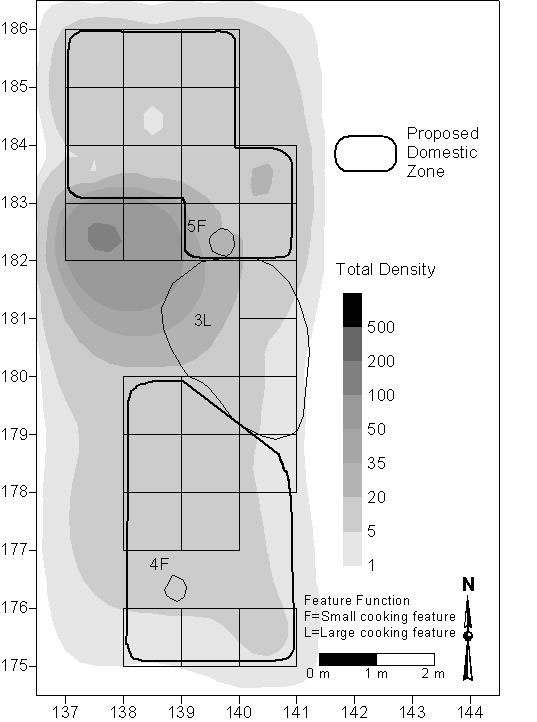

This plot of artifact density (in items per square meter) from one

Middle Archaic component at the Beene site shows proposed "domestic zones" containing small

cooking features indicative of those found in residential structures. The large cooking feature

between the structures is more indicative of a non-domestic feature.  |

|