|

What is known as the “joint report” was written by the three Spanish “noblemen,” Cabeza de Vaca, Andrés Dorantes de Carranza, and Alonso de Castillo Maldonado. Of these men, Cabeza de Vaca emerged historically as the primary spokesperson, as he was the second in command and treasurer of the overall Narváez expedition. According to ethnohistorian Alex Krieger, the noblemen received considerable assistance from Estevan, “the black” who was owned by Dorantes and apparently knew more about geography, distances, and directions traveled than his "formally" educated colleagues. He was also more effective in communicating with the Indians they met on their long trek. Cabeza de Vaca´s own narrative was probably written in draft form by late 1537 but it was not published as a book, Accounts of the Disasters, until 1542.

Although the original joint report remains lost, a version of it was paraphrased and published in 1547 by the well-known historian Gonzalo Fernando Oviedo y Valdez in his book entitled General History and Nature of the Indies (i.e., the New World). Oviedo included additional information in his book that he obtained during his own interviews with Cabeza de Vaca sometime between 1538 and 1541 before the latter´s departure in 1542 for what turned out to be an unsuccessful term as Governor and Captain General of the South American province of Rio de la Plata, also known as Paraguay.

Cabeza de Vaca´s governorship of Paraguay, according to Martin Favata and Jose Fernandez's translation, “gained him the enmity of officials in Asuncion" due, in large measure, to the unpopular and certainly unusual high-regard he had for Indian people. Upon arrival in Paraguay, Cabeza de Vaca implemented a “progressive, reform-minded program” that required the “clergy to take the Indians under their care,” mandated that “mistreated Indians were to be taken from their masters and put in worthier hands,” and made it “unlawful for Spaniards to buy any slaves taken by the Guarani Indians in tribal warfare.”

Discontent among the wealthy Spaniards in Paraguay culminated with a revolt in 1544 that led to Cabeza de Vaca´s arrest, his transfer to Spain in chains, his imprisonment and trial, which ended in his exile to Africa. His wife expended all her property in an effort to overturn the banishment and, eventually, he was allowed to return to Spain. In 1556, Charles V awarded him a monetary settlement and named him Chief Justice of the Tribunal of Seville. Cabeza de Vaca devoted most of his post-exile life to the second edition of his narrative Accounts of the Disaster, which was published in 1555 and included his sojourn to Paraguay. He died soon thereafter, within a year of his appointment as Chief Justice.

It is noteworthy that Cabeza de Vaca is well known for the high regard he selectively had for some Indian groups encountered in Texas, as well as for his avid criticism of the cruelty his fellow Christians demonstrated in subjugating and enslaving the native people he met in northwestern Mexico. His respect, no doubt, stemmed from knowing that it was by the grace of the Indians he encountered all along the way that he survived at all. It also seems likely that Cabeza de Vaca and his fellow trekkers survived and occasionally prospered, in no small measure, because they successfully demonstrated their respect for the native people with whom they lived. In a food-rich land where many of his Old World compatriots nonetheless had already died of starvation, Cabeza de Vaca seems to have learned quickly, albeit not necessarily enjoyably, to respect the peoples´ food-getting ingenuity. The Yguazes, for example, lived in a relatively root-rich homeland (the lower Guadalupe River basin) and frequented the tuna-rich South Texas heartland. Yet, from time to time they subsisted on spiders, ant eggs, worms, lizards, salamanders, wood, ground bones, earth, and deer dung. Of them, Cabeza de Vaca wrote “I believe truthfully that if in that land there were rocks, they would eat them."

European chroniclers, whether explorers, clergyman, travelers, or settlers, who wrote about Texas during the colonial era almost always derived their knowledge about native lifeways from observations made during passing encounters with Indians. In marked contrast, Cabeza de Vaca and his fellow survivors were participant-observers who lived with, and as, Texas Indians, day in and day out for just under seven years. From their writings and Oviedo´s interpretations, however, these “noblemen” clearly thought of themselves as “being slaves of the Indians.” As an anthropologist and veteran Peace Corps volunteer of interior Brazil, I might term their experience more charitably as “living with the locals under difficult circumstances.” In describing how the surviving castaways ended up living with different groups along the coast and inner Gulf Coastal Plain, Oviedo wrote:

"And there they were taken as slaves, [the Indians] making use of them more cruelly than a Moor would, because besides being naked and barefoot along the coast (which burnt during the summer) their work was nothing else but to carry loads of firewood and water and everything else that the Indians needed, naked as they were and pulling canoes through those overflowed places [aneguados] in such hot weather… As they [the Christians] were noblemen and good men and inexperienced in such a life, it was necessary that their patience be as great [as] and equal to the hardships and sorrows in which they [the Indians] had them, in order to suffer so many and such unbearable torments." -Oviedo (Krieger 2002:269-270).

The survivors' accounts are replete with statements about being cold and hungry, on the verge of starvation, going days without eating anything at all. They complained bitterly about being mistreated by many of the groups in whose custody they were held. The very fact, however, that the four men not only survived but prospered from time to time hints that some of what they reported should be read as figures of speech rather than taken literally. Today for example, some folks might well note, after an overnight springtime or fall camping trip somewhere in the middle San Antonio River valley that they “nearly froze to death” even though the temperature was well above freezing. To write about eating nothing but dried mullet, bitter roots, or even sweet tunas several weeks at time, might be well be the equivalent of my own carping as a Peace Corps volunteer when I complained that all I ever ate was manioc in one form or another when, in fact, my diet was much more varied.

For men accustomed to tailored clothing, walking about the Texas landscape in the middle of the Little Ice Age, sparsely clad or naked, it probably seemed very cold indeed. As reported by Oviedo, “the north [wind] blows in winter, when even the fish freeze, inside the sea, from the cold” and a single day would bring “snow and hail.” Indeed, fish kills due to extreme winter cold fronts are well documented along the Texas coast today. For the “noblemen” to work like native women or enslaved Moors must have felt like slavery indeed. Estevan, of course, probably had a rather different perspective on slavery. Ironically, it is because of Estevan´s status as a slave to the Spanish that we can only ponder what might have been learned about South Texas foodways directly from him. |

Frontispiece from the 1555 version of La Relación, Cabeza de Vaca´s account of his journey and struggles in Texas and Mexico. Image courtesy of the Center for American History, University of Texas at Austin.  |

| The noblemen received considerable assistance from Estevan, “the black” who was owned by Dorantes and apparently knew more about geography, distances, and directions than his colleagues, and he was more effective in communicating with Indians they met on their long trek. |

Emperor Charles V of Spain.  |

Ant eggs, deer dung, and lizards were among the many foods eaten by the Yguaze Indians of south Texas, whose resourcefulness earned Cabeza de Vaca´s respect. As he noted, “I believe truthfully that if the land were rocks, they would eat them.” Photo credits, left and right, John C. Abbott Nature Photography; center, Susan Dial.  |

| In a food-rich land where many of his Old World compatriots nonetheless had already died of starvation, Cabeza de Vaca seems to have learned quickly, albeit not necessarily enjoyably, to respect the native peoples´ food-getting ingenuity.

|

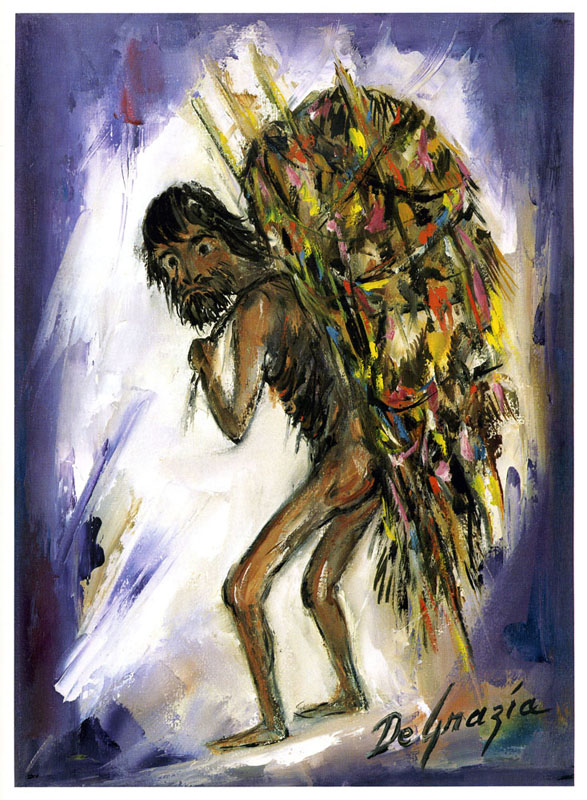

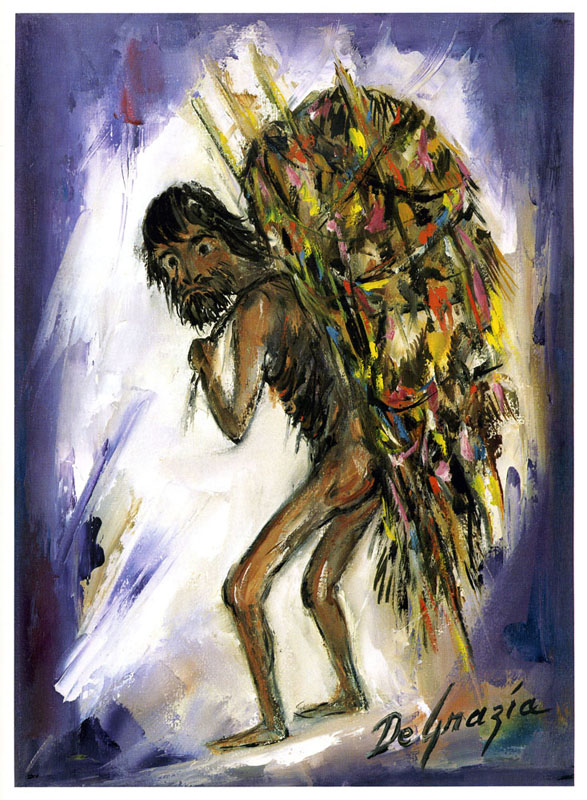

Cabeza De Vaca, traveling "naked and barefoot" in South Texas, as interpreted by artist Ted DeGrazia. Throughout this exhibit, the artist's remarkable paintings provide colorful reconstructions of scenes from the journey. Featured in "DeGrazia Paints Cabeza de Vaca" (University of Arizona Press), the images are made available courtesy of the DeGrazia Foundation.  |

|