Burial of the dead in a cairn grave atop a high ridge in west-central Texas, Late Prehistoric times. Painting detail by Frank Weir, TARL Archives. |

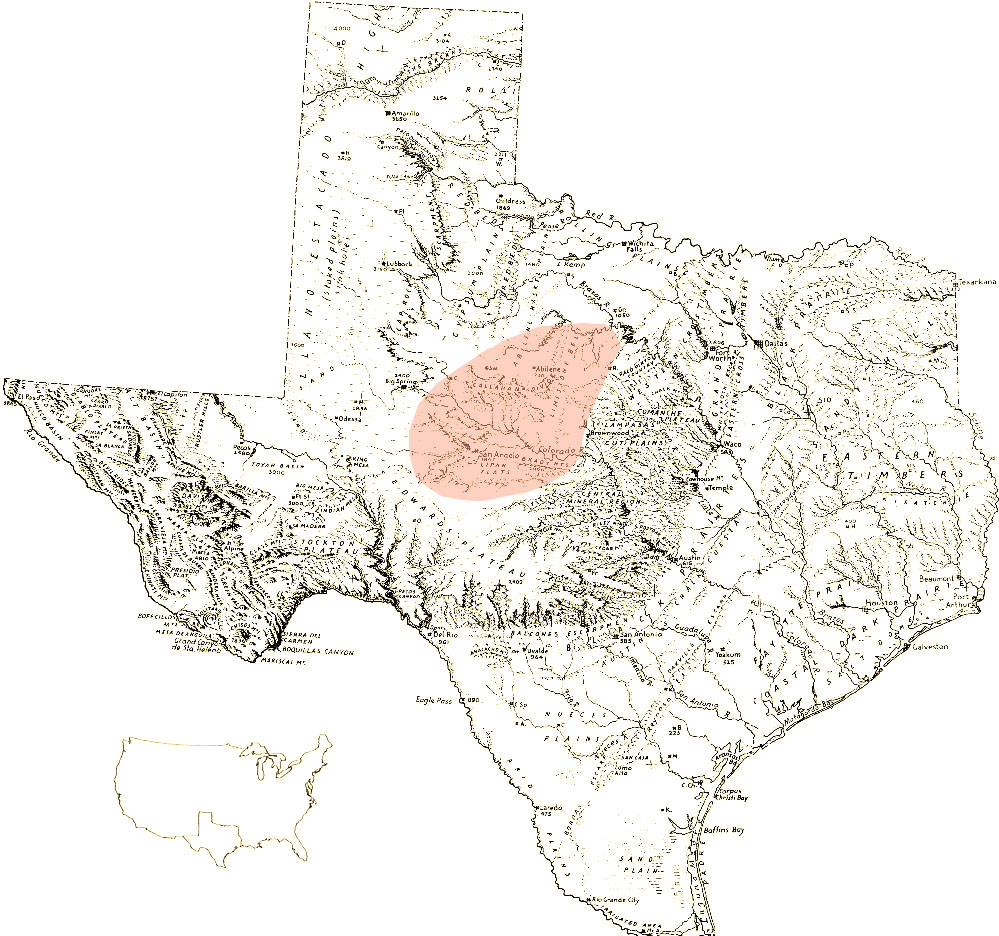

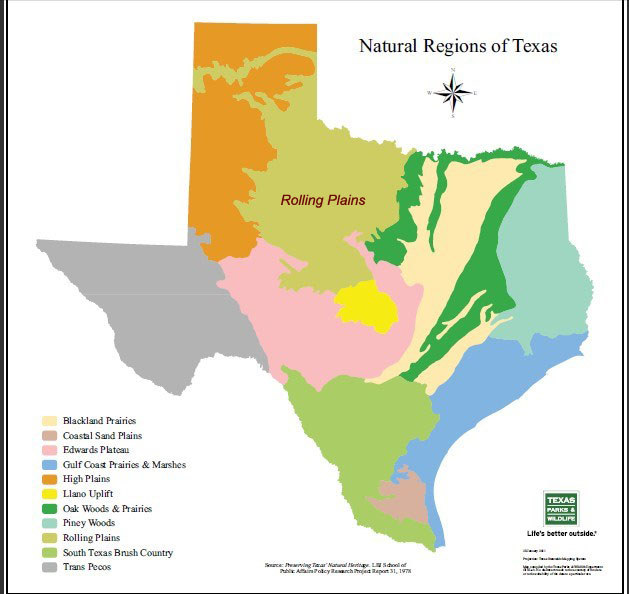

The countless stone mounds dotting the low hills and flat-topped mesas of west-central Texas have perplexed landowners and archeologists alike for more than a century. Known as “cairns,” these mysterious arrangements of rock can be found by the hundreds—and perhaps thousands—along the rocky ridgelines and bluffs overlooking the broad valleys of the Brazos and Colorado rivers and the canyons of their tributaries. Area ranchers typically have referred to these large cairn clusters as “Indian burial grounds”—and with good reason. Many of the cairns have been found to contain human remains—men, women, and children who long ago were carefully interred in specially prepared graves. The term cairn harks back to Old World usage describing a mound of stones erected as a memorial or marker. Although similar stone configurations have been observed in other regions of the state, those in the general vicinity of Abilene are distinctive in their quantity, scale and complexity. Varying widely in size, west Texas cairns typically have a discernible circular shape. They usually are located on prominent elevations that afford both panoramic vantage points and ready access to stone outcrops; indeed, several archeologists have noted the spectacular views afforded by the location of many of the cairns. Puzzling though they may seem to us today, these hilltop cemeteries mark special places on the landscape—sacred territory where kin and comrades once gathered for rituals and memorials. They speak to a little-known prehistoric era of human turmoil, transition, and rivalry, a Native American world that existed in the centuries before the entry of Europeans into the region and the arrival of the Comanche and Apache. The Land and ResourcesIn west-central Texas, much of the cairn burial distributional area lies within the southern portion of the Rolling Plains and includes part of the Edwards Plateau. The region is bounded by the Edwards Plateau canyonlands to the south and the Western Cross Timbers to the east. Steep cliffs and canyonlands of the Caprock Escarpment mark the transition to the High Plains to the west. Cutting through the cairn region and separating the Brazos and Colorado River drainages from each other is a major landform known as the Callahan Divide, a low range of mesas roughly 25 miles long. As aptly described by archeologist Robert Mallouf, the Divide appears to “rise from the surrounding redbed plains like a massive flat-topped fortress ranging from east to west as far as the eye can see.” In the northern portion of the cairn region, the valley of the Clear Fork of the Brazos expands over a mile wide in some areas, while tributary streams and gullies create jutting promontories. In the southern sector, the Colorado is fed by the clear waters of the Concho and many smaller tributaries. The region is rich in natural resources that would have attracted people to the area. The wide river terraces and bluffs provided ideal camp sites with ready access to water, fuel wood, high-quality chert for tools and weapons, and a variety of plants and animals. Outcrops of eroded limestone and sandstone afforded an inexhaustible source of rock for building cooking features and cairns. Tracing PatternsCairn burials in this region appear to be mainly a Late Prehistoric phenomena dating from roughly A.D. 800 to about A.D. 1300, although there is some evidence suggesting the tradition began earlier. Beyond that tenuous time frame, there is little known about the culture that created them, or the circumstances of the deaths of those buried there. In a few burials there is clear evidence of conflict—arrow points still embedded in bone. Some skeletons lack mandibles, skulls and other elements, suggestive of a pattern of trophy taking seen throughout the greater Plains region during the Late Archaic and early Late Prehistoric times. But it is not at all certain that most of the burials are those of the victims of intergroup violence. Our understanding of the cairn phenomenon is hindered by several problems. Most of the sites have been disturbed, if not destroyed, by relic collectors. Only a handful have been systematically excavated by archeologists and, of those, a relative few have yielded diagnostic artifacts that might inform us of the culture from which they derived. Much of the investigation into cairn burials was done in the 1930s-1940s by archeological pioneers Cyrus Ray and E. B. Sayles. As dedicated as these early researchers were, their findings are difficult to associate with specific locations and provide little useful information to help address questions of cultural connections. Since that time, cairn excavations have been limited, arising largely from discoveries made during reservoir projects in the area. In the 1980s, archeologist Darrell Creel began a focused effort to search for and document cairn sites along the Middle Concho River. He delved into the archives of the Texas Archeological Research Laboratory, attempting to correlate the often cryptic field notes and sketch maps left by earlier researchers with the extensive artifact collections they had amassed. His quest evolved into a decades-long effort to reassess dozens of previously recorded cairn sites and plot them on modern maps and to document new ones. Based on the presence of early-type arrow points and other evidence in some of the graves, Creel believes cairn burials are related to a regional cultural expression he termed the Blowout Mountain phase, a volatile time period coinciding with increased movements of peoples across the Plains. As this exhibit demonstrates, much research still remains to be done to gain a more realistic view of the scale and parameters of cairn burials and the culture they represent. In This ExhibitThe following sections highlight much of what is known about cairns of west-central Texas including information from unpublished reports and manuscripts, journal articles of the 1930s and 40s, and more recent archeological reports. Much of the imagery, including artifacts and photographs, has not been previously available and is drawn together in hopes of guiding future research. The Investigations section focuses on efforts to record and excavate the sites and discern patterns in this cultural expression. Explore the Sites enables viewers to learn more about many of the excavated cairn sites via an interactive map. Cairns Deconstructed synthesizes the extensive variation in structure and mortuary traditions represented in these features. Cultures, Conflicts, and Connections considers patterns in a broader context and the possible architects of this cultural phenomenon. Credits and Sources acknowledges researchers and contributors and provides references and links for learning more about topics covered in the exhibit. |

|