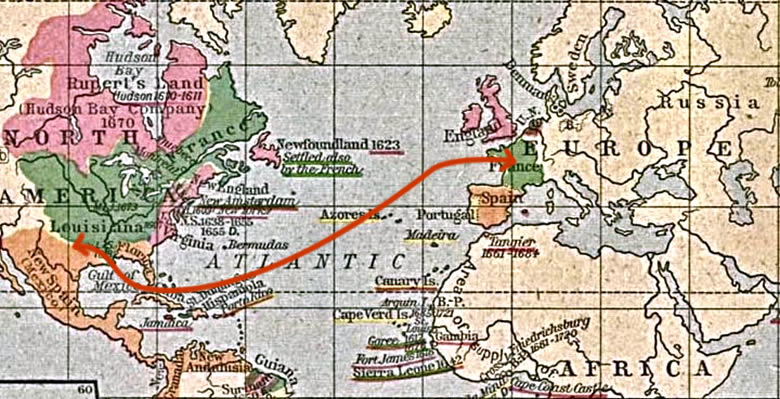

An Eighteenth-century French Connection in East TexasBy Jay C. Blaine

|

||

Base Map Source: Perry-Castañeda Library

Map Collection

|

||

| In 1962, a handful of metal and pottery artifacts from a Rains County site in East Texas was sent to the University of Texas for evaluation. At the time no one could have anticipated these few objects would be the first faint clues toward the identification of a significant commercial enterprise with international connections, based upon this site in the East Texas woods. Yet that is exactly what subsequent archeological investigations have shown. Some 250 years ago, the Gilbert site was the focus of a successful market-oriented endeavor linking East Texas with Europe. What was the market-driven and apparently successful product supplied by the people who occupied the Gilbert site? When did this take place, who were they, and how were the answers to these and other such questions sought and derived from the archeological evidence? Before attempting to answer these questions, let's take a look at the site. On the surface, the Gilbert site wasn't much to look at. Part of the site was a pasture and part was covered in woods, mainly post oaks and blackjack oaks. In places, one could make out low rises, about 30 feet across, which we euphemistically called "mounds," although "low heaps" would have been more appropriate. There were 20 of these scattered along the northern end of a sandy ridge overlooking Lake Fork Creek and one of its tributaries. The tallest "mound" towered about 18 inches above the surrounding terrain—most were even less conspicuous. We soon learned that these low heaps were actually middens—trash deposits that sometimes had firepits within them and almost always had lots of animal bone, most of it deer. Oddly, a few of the middens were capped with a layer of sterile (artifact-free) red clay—obviously an intentional addition, but for what purpose? Profile of Feature 7, showing thick cap of red

clay.

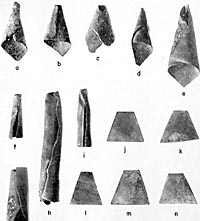

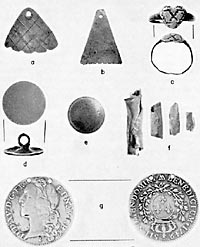

In the 1960s, it was assumed that each of the middens probably represented the location of a house and that the 20 house-middens represented a village that had been occupied during the mid-eighteenth century. The preponderance of French trade goods mixed with items of native manufacture including stone arrowheads, pottery, and bone tools was similar to that found at several other sites in north Texas including another Rains County locality, the Pearson site. These sites, including Gilbert, were considered part of the Norteño focus, believed to be linked to eighteenth- or early nineteenth-century occupations by Southern Wichita, Caddo peoples who apparently moved south into what is today Texas and Oklahoma from Kansas. Spanish authorities used the collective term Norteños, nations, or peoples of the north, in the eighteenth century. It referred to the Wichita and various other groups known to live within provincial Texas to the north of San Antonio beyond the effective control of the Spanish. The Norteño focus concept is no longer used much today; we have come to recognize that the archeological and ethnohistoric record is much more complex than was envisioned in the early 1960s. Trade Goods and Native ArtifactsThe Gilbert site has yielded what has proved thus far to be the most remarkably large and varied inventory of "trade" goods documented from an eighteenth-century Native American site in Texas. The extensive list of such European-supplied trade goods identified from the Gilbert site includes firearms, gunflints, lead bullets and shot (in ball form), axes and hatchets. There are also knives, brass kettles, brass and iron projectile points, hawk bells, glass beads, buttons, a finger ring, hoes (notably appearing unused), horse gear, and different sizes of cuprous (containing copper) wire bracelet stock. Many of these things had been discarded in apparently unused or still useable condition. One of the major artifact classes at Gilbert was firearms. All were flintlock smoothbores which proved to be of a lighter, hunting-type of gun as compared to the larger and heavier military "muskets" of the era. Detailed comparative study showed a major French influence in the design and decoration of these particular firearms. None were intact and it could be estimated from parts that at least 20 different long guns were discarded and mostly scattered about the site. Since so many gun parts had been cut or broken into pieces, as were other metal artifacts, it seems apparent that the Native Americans here were experimenting with the use of metal for a variety of purposes. The large quantities of diverse metal items appear to have been treated as a novel raw material and used in a variety of ways. Despite the obvious presence of firearms in numbers, no clear bullet damage was found on deer skeletal remains. One small triangular flint arrow point of the Fresno type was found in direct association with deer bones. A large number of the same type arrow point was found throughout the site. These, and the native-made gunflints, clearly show that a high level of skillful flintworking was maintained during this period despite the acculturation process indicated by so many European goods. While guns may have been the new weapons of choice, the bow and arrow was still in use. French clasp knife blade. Photo by Milton Bell.

Remnants of French-type brass kettles showed extensive wear. Some of the discarded kettles had been broken and cut up to create tinkler cones (ornaments attached to clothing). Examples of more than one variety of native-made pottery, including broken and sometimes repaired pieces, also were found. The presence of metal and ceramic containers again suggests that, during the mid-eighteenth century, the Native Americans at the Gilbert site were adopting foreign materials when convenient and desirable, but still maintaining traditional crafts. Native pottery was extremely common at the site. Over 2000 pottery sherds representing at least 47 individual vessels were recovered from the 1962 work alone. Among the many pottery types present in this collection are shell- and bone-tempered wares characteristic of the eighteenth century and a small number of grog-tempered (grog is ground-up pottery) vessels. The latter is probably Caddo pottery dating to several centuries earlier that represents an earlier use of the area. The grog-tempered sherds were found in only one small area of the site, the shell- and bone-tempered pottery was found in every excavation. In fact, one of the reasons that only a single group is thought to be responsible for the Gilbert site is because of the uniform distribution of ceramics and other types of artifacts across the site. Most of the shell- and bone-tempered pottery from Gilbert most closely resembled pottery from several sites along the Red River that were originally attributed to the Norteño focus as well. Several other vessels were recognized as historic Caddo pottery and were assumed to be trade pieces. Since the 1960s, many more late Caddo sites have been studied, and it is now recognized that bone- and shell-tempered pottery is relatively common at historic Caddo sites. In other words, the ceramics do not help pin down the identity of the group that lived at Gilbert. What was the source of the European trade goods?The European artifacts at the Gilbert site strongly point to French sources. While some degree of affiliation with French trade activity was expected because of the site's geographical location and anticipated general age, the 1962 excavation turned up evidence for a major commercial connection between the Gilbert site and France. In fact, the initial Gilbert site report published in 1967 was the first detailed archeological documentation of eighteenth-century French trade in the south-central United States. The apparent surplus of European goods hints that French traders themselves may have been present at the site, together with their merchandise. Alternatively, the trade goods could have been brought to the site by those transporting the hides to French traders living along the Red River. The hides would have been moved by horseback—horse bridle bits and the bones of at least one horse were found at the site. The use of horses also helps explain how such a quantity of heavy metal items—guns, hatchets, and kettles—arrived at the site. While the details of the trading are not known, it is clear that the deer-hide trade created such a wealth of foreign items that those who occupied the Gilbert site could afford to be wasteful. This circumstance bears a striking resemblance to the wealth of French trade goods present at the Trudeau site near the confluence of the Red River and the Mississippi in south-central Louisiana. Trudeau was the principal village of the Tunica between 1731-1764 and main source of the so-called "Tunica Treasure," a vast amount of high quality European trade goods that were surreptitiously removed from Tunica graves. The Tunica were middlemen in the French-Indian trade network and were especially prominent because they controlled the trade in horses. It is possible that the Tunica at Trudeau were involved, at least indirectly, in the deer-hide trade that figured so prominently at the Gilbert site. Anyone seriously interested in the topic should read The Tunica Treasure, a marvelous 1979 study by archeologist Jeffery Brain that tells the intriguing story of the Tunica and the treasure. |

||