Signs of home. A heart-shaped stone still

hangs on a gate post to secure a long-missing gate. A rock-edged

pathway leads to the front doorway. Photo by Susan Dial.

|

In ruin: interior of house as viewed by

TARL archeologists in 1989. Photo by Susan Dial.

|

|

"The holes between the logs would get so large you

could throw a cat through them!"

|

Photo of the house circa 1915. The frame

sleeping porch extends across the front of the house and the

kitchen has been added to the rear. Courtesy Fred Haas.

|

Ash-filled trash heap outside rear wall of Haas house contained

a variety of burned bone, glass, and metal objects. Residents

apparently kept the yard area swept and burned trash behind

the house. Photo by Susan Dial. |

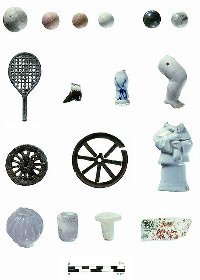

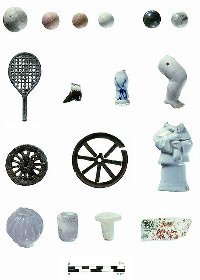

Remnants of past pleasures. Marbles, toy

parts, pieces of china dolls and figurines, and decorative

glass bottle stoppers found in the Haas house.

|

"In small things forgotten…."

The souvenirs and treasures of pioneer families: top row,

left to right, Brunet and Mattingly Ice Co. token, ca. 1880;

2 Pfennig German coin, 1875; gold hoop earring; bone or ivory

tuning key; mother-of-pearl fan brace. Bottom row, left to

right, brass Centennial badge, 1876; decorative belt buckles;

brass luggage tag marked, "International Traveler's Association,

Dallas, Texas, USA." Photo by Elizabeth Andrews.

|

Examples of the many bottles and jars found;

some provided important clues in dating the site.

|

Bits of harness, tack, and saddlery are reminders of the farm

animals at the site. At top left is a small brass harness bell;

at bottom left, a saddle pommel. |

The Haas house after restoration completed. Photo by Tom Hester.

|

|

Investigations at the Doeppenschmidt-Haas house

combined many lines of inquiry to date the structure and

determine its period of use. Documentation of the structure,

survey of the grounds, and test excavations within the house interior and two

dump areas outside produced a quantity of artifacts and data. Perhaps most valuable, however, was having one of the former occupants, Fred

Haas, as a "co-investigator." Mr. Haas provided

a colorful and poignant look back at the farmstead during

its heyday and corrected the

archeologists' interpretations of several enigmatic features. His recollections

are woven into the account of archeological findings.

The Haas family moved to the log house shortly after 1901, the year Fred Haas was born. Although

he was nearly 90 when he was interviewed for this project,

his memory was sharp and his storytelling abilities unfettered

by age. Although poor health prevented him from being at the

site during archeological investigations, he returned for a celebration

with his family and the current owners following the restoration of the house.

On viewing the painstakingly rebuilt log structure, he exclaimed

in typically forthright fashion, "The house never looked

this good!"

Life in a One-room House

Although no recorded information was found pertaining to the builder

or date of construction of the log house, construction

techniques and certain artifacts suggest it was built sometime in

the 1870s. In contrast to the cruder, more hastily built log cabins

built by the earliest settlers of Texas, the Doeppenschmidt-Haas

house was well constructed and built for permanence, drawing on

building traditions developed in Europe and the upper southern United

States. The half-dovetail notching used is a construction type associated

with fine craftsmanship that, according to cultural geographer Terry

Jordan, suggests the hand of a knowledgeable workman rather than

a communal barn-raising effort by neighboring farmers.

The house is a roughly square, single-pen dwelling made of hand-hewn

cedar logs stacked horizontally, joined at corners with a combination

of half- and full-dovetail notching, and secured at the upper plate

with cedar pegs. Chinking between the logs was a mix of mud and

small stones, plastered over with a lime slurry. Haas recalls that

re-chinking had to be done by the family about every spring: "The

holes between the logs would get so large you could throw a cat

through them."

A front porch once extended across the front

of the house, and it is shown in the circa 1915 photo of the

house. It was there that family members slept on warm nights

when the one-room house became too confining. It was there

also that Haas believes one of the former residents was kept

"locked up." "They claimed he'd lost his mind,"

he said. This recollection corresponds with census records

for 1880 that list Phillip Doeppenschmidt as "temporarily

insane and paralyzed." Doeppenschmidt, who died in 1881,

was buried at the hillside cemetery

several miles from the house.

For Haas and his three brothers and sisters, life

in the one-room house was cramped but pleasant. Haas recalls his

mother cooking in an iron kettle in the large fireplace and heating

water there for family baths. Water was hauled from the creek several

hundred yards down the hill. In subsequent years, a shed room was

added for a kitchen at the rear of the house.

During his childhood, Haas wandered freely across

adjacent properties in the Hill Country. His mother allowed neighbors

to bring stock onto her property for water from the creek during

times of drought. Others from the area remember that cattle and

stock were branded and allowed to roam free among the large ranches.

As barb wire fencing became increasingly popular in Texas after

about 1880, the easily climbed dry-laid rock walls were gradually

replaced.

The Artifacts

Artifacts found during tests dug in the house

interior bore out the varied activities that took place in

the house. These ranged from toy parts and keepsakes to kitchenware

and animal bone. A great many mementos were found in a test

unit placed under the west window; among these were a German

coin, a gold earring, a porcelain figurine, and a pocketknife—all

small enough to have slipped through cracks among the floor

boards. The same may have been true for the many buttons recovered,

fifteen of which were in front of the north doorway. Perhaps

a pioneer woman sat there with her handwork and sewing to

catch the breeze and natural light. Haas recalls, however,

that as a child he dropped coins and buttons through the floorboards.

Fragments of stoneware and glass storage containers

as well as bottles of patent medicine, snuff, and beverages were

found in test excavations in the house and in the two dump areas

outside the rock-walled yard. From the 1880s and later, these items

could be purchased at stores in Bee Caves, Cedar Valley, and Austin.

Haas recalls walking several miles to Cedar Valley to buy snuff

for his mother. He also recalls visits to Hallman's

store several miles away.

For larger purchases, the family periodically travelled

to Austin. The trip was a day-long process by wagon or on horseback

along Bee Cave Road, a rocky and rutted dirt lane so narrow that

cedar branches brushed the wagons. The road was not paved until

1936. Travelers crossed the Colorado River by ferry or, by 1890,

bridges over Barton Creek and the Colorado River.

Some of the artifacts—a brass luggage tag,

the German coin, ornate black glass buttons, beads, the earring,

and fragments of decorative bric-a-brac—are more unusual

items, particularly when considered in the context of the

rugged frontier lifestyle epitomized at the site. Several

appear to be the keepsakes of fairly worldly individuals who

had traveled in a large city. Such a profile might fit an

immigrant family—either Doeppenschmidt or Haas—who

had retained mementos of a land and lifestyle left behind.

Artifacts were analyzed both for clues for dating

the site as well as for information about the families themselves.

One interesting piece of information that emerged from the study

was the similarity of tableware and glassware used by folks in rural

areas and in the city of Austin during the roughly fifty-year time

period from 1880 to 1930. Vessels of plain white ironstone, or whiteware,

predominated until a wide array of colorful decorated styles came

into vogue in the early 1900s. That rural folk living on what were

essentially "frontier" farmsteads would share the same

style preferences with city dwellers and be part of a larger network

of commerce is testament, perhaps, to the far-reaching effects of

mail order catalogs.

Afterward

Although the house lacked such amenities as electricity,

indoor plumbing, or a well, it was occupied into the late 1930s

by families with as many as four children. At that point, the land

was purchased as part of a larger acquisition by the current landowners

who determined to restore the log house and protect the other historic

sites nearby. With Austin architect Joe Freeman overseeing renovations,

the house was brought back from ruin. The yard was cleared and landscaped

using native plants and the rock wall surrounding the house carefully

re-laid. Today the house, looking much as it did when first completed

by the careful craftsman over a century ago, is used as a family

retreat.

|

View of the Haas house prior to restoration.

Photo by Tom Hester.

Click images to enlarge

|

Hand-hewn cedar log walls with mud

and stone chinking. Plaster was applied over the walls

as a final seal against wind, bugs, and snakes.

|

Building materials, furniture parts,

and keys found at the Haas house. Square cedar pegs,

such as that shown at bottom left, were used to join

the log walls at the corner of the house.

|

A large, caved-in, rock enclosure

around these trees was puzzling to archeologists. Did

it mark a grave? A seep spring? Former resident Fred

Haas was tickled to tell us that it had been a pen for

hogs while he and his family lived at the farm. Photo

by Susan Dial.

|

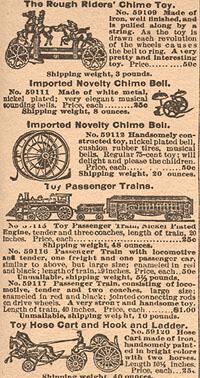

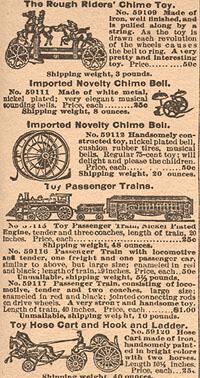

A look at some of the toys advertised

in the Fall 1900 Sears, Roebuck, Inc. Catalog.

|

Necessities and pleasures, these

items representing daily life range from a shoe-button

hook for a high top boot (middle row, left) to a Prince

Albert tobacco can, to a harmonica reed (bottom row,

right).

|

Beads and buttons, both fancy and

plain, provide a glimpse of how rural folk dressed near

the turn of the twentieth century.

|

Side view of restored house, with

chimney rebuilt. Wagon wheel hanging on chimney was

found in adjacent field. Photo by Tom Hester.

|

Interior of Haas house after restoration.

Photo by Tom Hester.

|

Fred Haas, who grew up in the log house, returns to see the newly restored structure.

|

|