Candelilla, commonly known as "yerba"

or the "weed," is sold as a medicinal tea in some Mexican

herb shops. Reportedly, juice from the plant also was

used as a remedy for venereal disease, hence the name

"Euphorbia antisyphilitica." Photo by Curtis Tunnell.

|

The plant thrives on rocky limestone

slopes, producing clusters up to 6 feet in diameter.

At that size, they often die down in the center leaving

a doughnut-shaped ring of candelilla. Photo by JoAnn

Pospisil. Click to enlarge.

|

|

Experiments in cultivating candelilla for wax production

have been unsuccessful. In one attempt, the land was

prepared and the candelilla was planted and "grew

like weeds," but when the enthusiastic entrepreneurs

began harvesting, they found the plants produced almost

no wax.

|

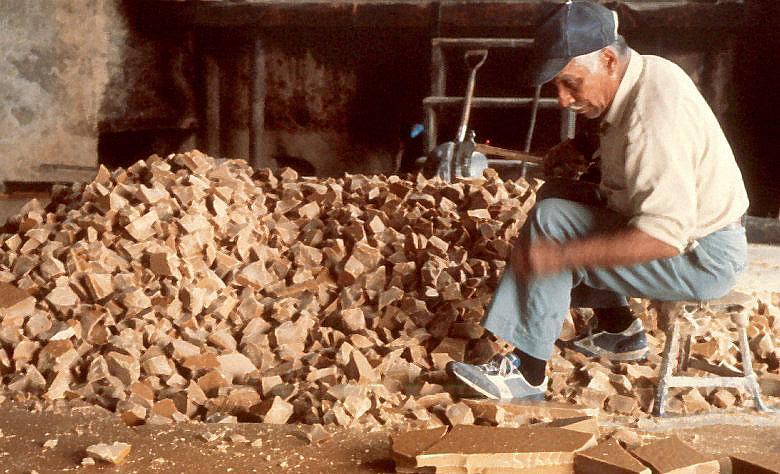

Carnauba wax, derived from the fronds

of the carnauba wax palm tree (Copernica prunifera)

of Brazil, is the hardest natural wax available and

is very heat resistant. The wax is sold in chips or

flakes, as shown at bottom. Historically, there has

been a greater demand for this wax than candelilla.

|

Like the hardy candelilla—which

can withstand long periods of drought and high temperatures

by thickening its waxy coating—lechuguilla plants

also are desert survivors with specific adaptation techniques.

Threatened by lack of moisture, this plant has shriveled

to minimize surface exposure but will fill out again

when rains come. Photo by Steve Black.

|

|

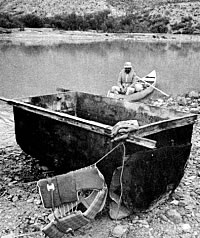

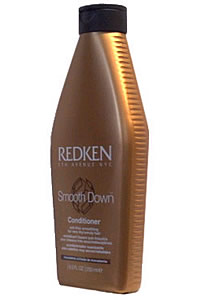

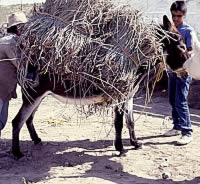

Various attempts to harvest candelilla with mowing

machines and bulldozers have failed. It seems that two

strong hands, a bent back, and a burro are still the

best way to gather the plant economically.

|

After plants are harvested, the plants

are carefully stacked into bundles of about 50 to 80

pounds each, tied together with a rope, and cinched

tightly with a wooden "honda." Photo by JoAnn Pospisil.

|

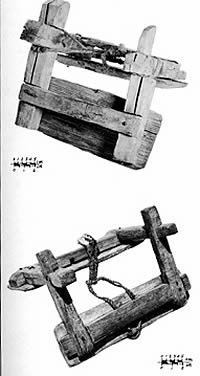

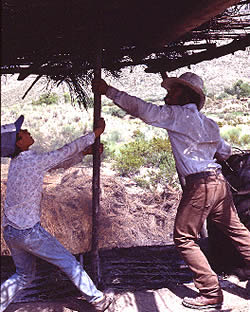

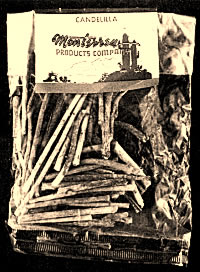

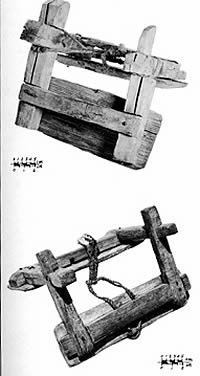

"Fustes" (packsaddles)

like these, when placed on a burro, will support four

bundles of weeds or two bags of wax. Photo by Curtis

Tunnell.

|

Rope, or "mecate," made of lechuguilla

fiber, used to tie bundles of candelilla. Photo by Curtis

Tunnell.

|

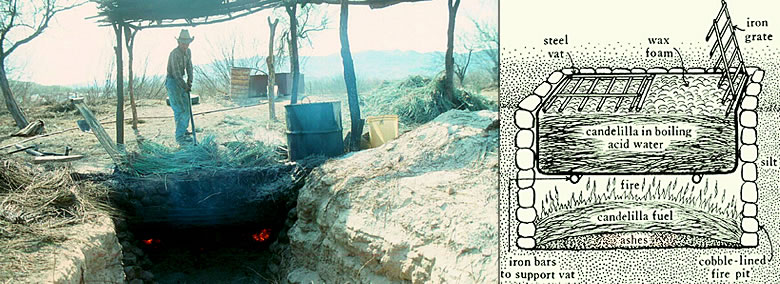

Pitchforks are used to lift plant

stalks into the vat. The handmade version, carved from

a mesquite branch, is far more common in the camps than

the manufactured tool (shown on left). Drawing by Curtis

Tunnell. Click to enlarge.

|

|

The Candelilla Plant

Candelilla is known as the "weed"

to those who work with wax in west Texas, while the Mexican

laborers simply call it "yerba." The botanist J.G.

Zuccarini first described the plant for the scientific world

in 1829 and assigned it the name Euphorbia antisyphilitica.

It is curious that he did not discuss the plant's wax but

did mention juice from the plant being used by the indigenous

peoples as a remedy against venereal disease. Some Mexican

herb shops still carry candelilla as a medicinal tea.

In 1909, G. Alcocer presented a new description

of candelilla, named it Euphorbia cerifera, and discussed

the fine wax produced by the plant. Alcocer's species is considered

synonymous with Euphorbia antisyphilitica Zucc. and

is the primary species of the plant utilized in wax production.

Other minor species also occur in the Chihuahuan Desert. The

common name candelilla probably was applied to the plant because

of its small, erect, wax-coated stems, which resemble little

candles.

Candelilla is a perennial and is found in locally

abundant stands in Mexico in northern Zacatecas, western Nuevo

Leon, eastern Durango, and scattered throughout Coahuila and

Chihuahua, and in Texas in El Paso, Hudspeth, Presidio, Jeff

Davis, Brewster, Terrell, and western Val Verde counties.

Small, isolated populations have been reported in southern

Texas and the Mexican states of Guanajuato and Hidalgo.

The plant commonly grows on well-drained limestone

slopes but is occasionally found associated with igneous rocks,

and it does not seem to grow well in bottomlands and clayey

soils. The root system is small but each plant supports numerous

erect stems, which are mostly simple but occasionally are

branched. A plant of moderate size may produce as many as

100 stems and be, in aggregate, from 1 to 2.5 feet in diameter.

The stems range from about 1 to 2 feet in length and 1/16

to 1/3 of an inch in diameter and are grayish green in color.

In the wax camps we have occasionally observed an unusually

large plant with stems at least 3 feet in length.

Where candelilla has a chance to grow normally,

the plant clusters get larger and larger until they may be

as much as 61/2 feet in diameter. When they get that large

they begin to die down in the center and leave a doughnut-shaped

ring of candelilla. Near McKinney Springs in 1980 we found

plant clusters of this shape that had rabbit nests in the

center of the ring. Detailed botanical descriptions of the

plant can be found in Trees, Shrubs, and Woody Vines of

the Southwest by Robert Vines and in Manual of the

Vascular Plants of Texas by D.S. Correll and M.C. Johnston.

The candelilla plant has been observed flowering

from April through August, apparently coinciding with spring

and summer rains. Stands of the plant seem to be most abundant

at elevations around 2,500 feet and are commonly associated

with lechuguilla, sotol, chinograss, ocotillo, and various

cacti. Severe freezes at higher elevations are said to kill

the plants back to their roots. Candelilla is generally a

very hardy species and not particularly susceptible to diseases

or pests. It does serve as occasional forage for goats and

rabbits. Texas A&M palynologist Vaughn Bryant says candelilla

produces small amounts of pollen, which is sticky and tends

to fall directly to the ground. Candelilla pollen is unlikely

to be widespread or abundant and probably is rare in the archeological

record.

The wax of the candelilla is an epidermal secretion

on the stems that helps conserve internal moisture of the

plants during severe hot and dry periods. The wax, which forms

a scurfy coating on the stems, is much heavier in the dry

season of the year and during periods of drought. Since average

annual rainfall in the desert where candelilla flourishes

ranges from about 4 to 20 inches, drought is not an uncommon

condition. The moisture-protecting mechanism of the plant

is apparently effective for, as Big Bend writer Virginia Madison

has said, "You seldom see a dead candelilla plant."

The summer of 1980 was unusually hot and dry

and many desert plant species such as lechuguilla and Spanish

dagger suffered from desiccation, while candelilla seemed

to suffer very little damage. Plants can be dug up and kept

for long periods of time, and, even after the stems have become

longitudinally wrinkled, the plant will recover when replanted

in the soil. When cut or broken, the stems "bleed"

a white, milky substance, and, if the plants are harvested

by cutting, the root systems will die.

According to a 1953 study by botanists W.H.

Hodge and H.H. Sineath, candelilla is the second most important

vegetable wax after carnauba, which is extracted from a Brazilian

palm. About ten tons of the plant can be harvested per acre

where it grows abundantly, far less in most harvest areas.

Since primitive wax-extraction methods produce a yield of

only about 2 percent of plant weight, the refiner who marketed

one million pounds of wax in a good year was representing

exploitation of about 50 million pounds of wild plants from

2,500 to 5,000 acres of desert. Five or ten times that much

wax may be imported annually from Mexico, representing denuding

of perhaps as much as 50,000 acres of desert of candelilla

growth. Can any desert species survive this magnitude of exploitation?

Apparently candelilla has done fairly well, because wax production

continues after seventy years.

The plants need from two to five years of growth

before they produce significant wax. When we asked many informants

familiar with wax making and marketing how long it took for

candelilla growth to return in an area that has been intensively

harvested, the estimates ranged from five years to fifty years.

All of these estimates may be accurate for different areas

and conditions. Wax refiner David Adams was more specific

and said that after a first harvesting the candelilla will

return in some abundance in two years; after a second harvesting

it takes about five years for candelilla to come back; and

after a third harvesting it might take ten years for there

to be enough plants for economical harvesting. He said in

some areas of northern Mexico they have depleted the candelilla

through overexploitation and are now using pickaxes to pull

out lechuguilla and greasewood in order to get the small amount

of candelilla growing around those plants. In normal harvesting

they would pull out the candelilla that is easy to recover

and leave plants in and around lechuguilla to help the stand

grow back.

In recent years the hearty plant has been transported

widely as an ornamental, and it is reported to grow more robustly

than in the native habitat but to produce little or no wax

under protected conditions. Cultivation of candelilla for

wax production has been attempted in Haiti, Cuba, and the

Dominican Republic but these efforts have failed. A local

informant said he was involved in an expensive experiment

to grow candelilla near Laredo, Texas. The land was prepared

and the candelilla was planted and "grew like weeds,"

but when the enthusiastic entrepreneurs began harvesting,

they found the plants produced almost no wax. Other attempts

at cultivation and mechanical harvesting of candelilla in

the Presidio area were equally unsuccessful. Harvesting native

stands of the plant and processing the wax under primitive

conditions remains the best and perhaps only method of extracting

candelilla wax.

Despite the failure of cultivation efforts and

continued exploitation of the wild plant, candelilla probably

will not be threatened with extinction. Some plants will grow

back from remnant root fragments, and others grow in inaccessible

niches where gathering is impractical. However, some scientists

fear that, after harvesting, candelilla may never return to

its original abundance and balance in the vegetation community.

The impact of the weed harvesting on the desert environment

in general and on associated sensitive plant communities in

particular is a matter of concern to biologists in the Chihuahuan

Desert.

Harvesting the Plant

Various attempts to harvest candelilla with

mowing machines and bulldozers have failed. It seems that

two strong hands, a bent back, and a burro are still the best

way to gather the plant economically. The gatherers (arrieros)

arise in the wax camps at dawn, and after a breakfast of coffee

and tortillas, each man rounds up his hobbled burros and prepares

from four to six animals for the day's work. Each burro gets

a small wooden packsaddle (called a fuste, or occasionally

aparejo), and, if the man is careful with his animals,

a saddle blanket (corona) of burlap.

One informant said he had seen burros with large

galled spots on their backs from carrying burdens without

proper padding under the saddles. The man will ride on a favorite

burro, behind the packsaddle, and carry a bag of tortillas

with frijoles and chiles, and a plastic bleach bottle of river

water. He may travel from a few hundred yards to as much as

five miles, depending on how long the camp has been active,

in order to find good candelilla growth. When a slope with

good growth is located, he hobbles the burros and begins the

hard, solitary work of "pulling weed."

The plants are usually pulled up by hand, but

a sharpened stick may be used as a primitive spading fork.

After dirt and rocks are shaken from the roots, the plants

are thrown into wind-rows until a large quantity has been

gathered. Then a rope 10 to 12 feet long (called a mecate)

made in a local fabrica from lechuguilla fiber is laid

out on the ground, and the plants are carefully stacked on

it with root ends alternating with tips. About 50 to 80 pounds

of plants are tied in a bundle with each rope, using a honda

to facilitate cinching and quick release of the load. Later

in the day the burros are rounded up, and four bundles of

weed are tied on the packsaddle of each animal.

When asked how much candelilla can be carried

by each burro, one candelillero (wax worker, or cerero)

responded: "That depends entirely on the conscience of

the man—one man may put 250 or even 300 pounds on a burro,

while another man will never put over 150 pounds on his animals."

So six burros and one man may bring in 1,200 pounds of weed

which, when processed, will yield about 24 pounds of wax.

The weed is stacked in orderly piles in the camp and may be

stockpiled for days or weeks until it is time for it to be

boiled for removal of the wax.

The wax gatherers pull all of the accessible

plants they can find in an area before they move on to another

stand of plants, so a broad band around each wax camp is denuded

of plants before the camp is moved to another location along

the river. In the past, the gatherers commonly forded the

river and gathered weed indiscriminately in Texas and Mexico,

taking no particular note of ranch or park boundaries unless

forced to do so.

Over the years, the National Park Service has

increased efforts to control illegal harvesting of candelilla

in Big Bend National Park. In May 1980 a park official said

they had caught a large burro train loaded with candelilla

on Mesa de Anguila. The cereros (or candelilleros)

were carrying candelilla down a treacherous trail and across

the river to a wax camp about two miles up a tributary toward

San Carlos. The burros were confiscated and the men turned

over to Mexican authorities. These cereros were double smugglers—carrying

weed out of the park and across the river to their camp and

then bringing the extracted wax back across the river to a

buyer.

The Park Service planned other raids on wax

operations during the 1980s study. A camp on the Mexican side

of the river in Boquillas Canyon was sending burro trains

up a tributary canyon on the U.S. side to gather weed in the

park. The Park Service planned to have enforcement personnel

go down the river, seal off the trail, and trap the gatherers

in the park with heavy loads of candelilla. Increased poaching

of candelilla in the park is another indication that the weed

is being overexploited in Mexico.

Boiling the Wax

|

|

In This Section:

The Candelilla Plant

Harvesting the Plant

Boiling the Wax

Refining the Wax

A Look at The Wax

Uses for Candelilla Wax

|

Candelilla is found in abundant stands

in northern Mexico and in several west Texas counties.

Click to enlarge.

|

Burros nibble on harvested candelilla.

When growing, the plants serve as occasional forage

for goats and rabbits. Photo by Raymond Skiles. Click

to enlarge.

|

The plant likely was named candelilla

because its small, erect, wax-coated stems resemble

little candles. The plant usually requires two to five

years of growth to produce enough wax to harvest productively.

Photo by JoAnn Pospisil.

|

|

The moisture-protecting mechanism of the plant is

apparently effective: you seldom see a dead candelilla

plant.

|

Small yellow-red flowers emerge periodically

on the pencil-like candelilla stalks in spring and summer,

apparently in response to rains. Photo by Glenn Evans,

courtesy of the Texas Memorial Museum.

|

Rising early for the day's work,

Dimitrio Diez cooks a breakfast of tortillas on a make-shift

griddle. Photo by Raymond Skiles. Click to enlarge.

|

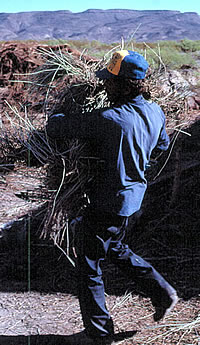

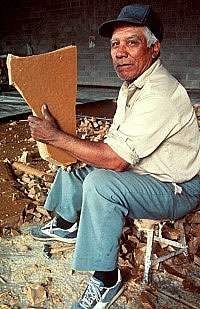

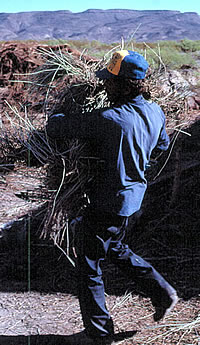

Strong arms and a sturdy back. A

candelillero (or wax worker, "cerero") hauls

an enormous bundle of candelilla. The plants are typically

harvested entirely by hand, or with the aid of a sharpened

stick. Photo by Raymond Skiles. Click to enlarge.

|

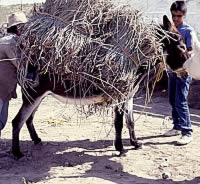

Workmen load a burro with bundles

of harvested candelilla. The animals haul the plant

stalks to the processing area, close to water and camp.

Photo by JoAnn Pospisil.

|

|

When asked how much candelilla can be carried by

each burro, one candelillero responded: "That depends

entirely on the conscience of the man-one man may put

250 or even 300 pounds on a burro, while another man

will never put over 150 pounds on his animals."

|

|