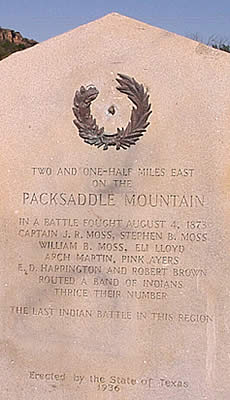

Anglo marks on the Hill Country frontier:

Army posts and some of the settlements in the 1840s

and 1850s.

|

Fort Martin Scott, established in

1848 in Fredericksburg, was tasked with guarding the

German settlements on the western frontier. Here, history

interpreters depicting soldiers of the 1840s practice

drills in front of the guardhouse at the fort. Photo

by Roy Betzer, courtesy the Gillespie County Historical

Society.

|

|

It was quickly evident that most of the forts were

located too far east—on or behind the frontier

of settlement—to give even mounted troops a chance

to do anything about the raiders except chase them after

they had struck.

|

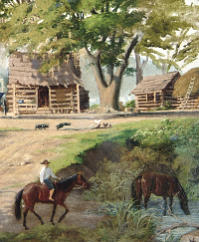

Llano County pioneer Gustave Schleicher

was a member of the Bettina Colony, established by the

Adelsverein in 1847 along with Castell and several other

small burgs on the Llano River. With the exception of

Castell, none of these early settlements —made

up chiefly of highly educated German freethinkers—survived.

Painting in Llano County Museum, Llano, Texas, gift

of Sam Schleicher.

|

Situated high on a hilltop, this

reconstructed building at the site of Fort Mason commands

a view of the town below. Photo by Susan Dial.

|

Dutch House in Frederickburg, Texas,

Residence of the Parson, January 28, 1849. Detail of

sketch by Seth Eastman. Courtesy of the McNay Art Museum,

gift of the Pearl Brewing Company.

|

Reconstructed ramada shelter at site

of Fort Inge. The post was situated on the Leona river

west of Castroville, near the present-day town of Uvalde.

In the foreground is a wall made of igneous rock from

nearby Pilot's Knob. The low stone foundation of a fort

structure is visible in the background. Photo by Susan Dial.

|

|

By the mid-1840s, white settlement pierced the

Balcones Escarpment and began to creep up the Plateau's river

valleys. The first of these extensions was the colony of French

banker-diplomat Henri Castro, who settled his Alsatian immigrants

in the Medina River valley west of San Antonio. German immigrants

were drawn to the huge Fisher-Miller tract between the Llano

and Colorado Rivers, but settled first on the Guadalupe River

north of San Antonio and the Pedernales River to the northwest.

These communities—New Braunfels and Fredericksburg, respectively—combined

with Castroville to constitute what was considered at the

time to be the "Western Frontier" of white settlement

in Texas.

.

At the end of the United States' war with Mexico in 1848,

protection of Austin and the German and Alsatian settlements

became the responsibility of the U.S. Army. The southern anchors

of a "frontier line" of forts were placed near the

edge of the Edwards Plateau. Fort Martin Scott was established

in 1848 at Fredericksburg, the settlement most exposed to

Plains Indian raids. Then followed Fort Croghan, located near

the Colorado River above Austin; Fort Lincoln, on Seco Creek

north of the Alsatian hamlet of D'Hanis; and Fort Inge, on

the Leona River west of Castroville.

Although Fredericksburg may have appeared to

be the most vulnerable settlement, defense of the Castro Colony

occupied more of the Army's attention in the early 1850s.

The settlements at the base of the Balcones Escarpment frequently

were victimized by Indian raiders, and companies of the 2nd

Dragoons from Fort Inge and Fort Lincoln occasionally were

able to conduct a fruitful pursuit.

It was quickly evident, however, that most of

the forts were located too far east—on or behind the

frontier of settlement—to give even mounted troops a

chance to do anything about the raiders except chase them

after they had struck. The army's answer to this problem was

to abandon most of the original "frontier line"

of forts and to construct a second series of posts farther

west.

A garrison was retained at Fort Inge, the westernmost

of the original posts. Forts Croghan, Martin Scott, and Lincoln

were vacated. Fort Mason was established about 40 miles northwest

of Fredericksburg as a replacement for both Croghan and Martin

Scott. Fort McKavett was located near the headwaters of the

San Saba River, about 40 miles west of Fort Mason, and Fort

Terrett was placed about 40 miles south of McKavett on the

north fork of the Llano River.

Forts McKavett and Terrett were situated near

one of the Comanche travel routes from the Plains into Mexico.

This was a matter of some consequence. The United States,

as part of the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo that concluded

the Mexican War, had agreed to try to stop Indian raids into

Mexico. Fort Inge, about 125 miles almost due south of McKavett

and just off the Edwards Plateau, gave the army a third post

near the Comanche trail.

This scheme, though logical, was at first ineffective.

Fort Terrett was abandoned in 1854, only two years after it

was established. Fort McKavett lasted seven years, but there

are no reports of Indian fights involving troops from the

post during that time. Companies of the 2nd Dragoons and the

Regiment of Mounted Riflemen garrisoned at Fort Inge directed

most of their attention to the Nueces Strip—the plain

between the Nueces River and the Rio Grande—because of

the frequency of raids on ranchos near Laredo.

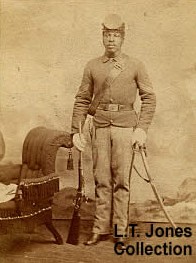

The situation changed in 1856, with the arrival

and deployment of the 2nd Cavalry. This regiment was to become

one of the most celebrated units in the history of the United

States Army, and included 16 future Civil War generals among

its officer corps. Its commander, Colonel Albert Sidney Johnston,

established headquarters at Fort Mason.

Johnston and the regiment's lieutenant colonel,

Robert E. Lee, put the unit to the task of scouring the country

from the Brazos River to the Nueces—the entire Edwards

Plateau and then some—in search of Indians. The regiment

recorded more hostile actions against Indians than any other

U.S. Army unit in Texas prior to the Civil War. Nearly two-thirds

of the engagements occurred on the Edwards Plateau.

With the coming of secession and Civil War,

Texas frontier folk fell back on the same types of defenses

they had used during the Republic period: Texas-funded regular

troops (the "Frontier Regiment"), militia, and a

Frontier Organization that patrolled similarly to the rangers

of the Republic but functioned no more efficiently than militia.

By 1864, the frontier was under assault by northern Comanche

and their Kiowa allies.

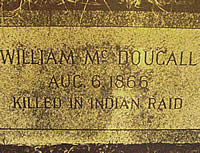

Reports received from some officials of frontier

counties indicate 163 settlers killed, 24 wounded, and 43

carried away by Indian raiders during the period from the

summer of 1865 to the summer of 1867. Many of these were no

doubt from the counties north of the Edwards Plateau, above

the Brazos River, where settlements were particularly vulnerable.

But anecdotal reports from the Hill Country reflect a serious

enough condition there. From Llano to Lampasas, the stories

were the same: it had been 20 years since the Indians had

been so numerous, so well-armed, and so bold; farmers were

regularly being shot down in their fields, or their livestock

driven away as they watched helplessly; the frontier was "breaking

up," would have to be abandoned.

After the war, the state was prohibited from

fielding its own defense forces. The U.S. Army was quick to

get troops to the Rio Grande, but moved much more slowly to

the western frontier. This reflected the army's concern, and

that of the national government, for the international boundary

and the post-war Reconstruction mission. One company of the

4th Cavalry was posted to Fort Martin Scott early in 1866

and another to Fort Inge. In November and December of that

year, two companies were sent to Fort Mason and three to Camp

Verde, south of Fredericksburg in modern Kerr County.

|

Home of Henri Castro, founder of

Castroville. Beginning in the early 1840s, Castro brought

settlers from Germany, Alsace-Lorraine, and France to

the far western edge of the frontier, some 30 miles

west of San Antonio. In spite of repeated Indian attacks,

disease, and severe drought in 1848, the community survived

and still thrives today. Photo by Susan Dial.

|

Buildings at Fort Martin Scott were

made of logs or of plastered limestone, the latter by

skilled German masons hired from among the Fredericksburg

populace. Photo by Susan Dial.

|

Early Fredericksburg kitchen. The

inviting warmth of the fireplace beckoned weary settlers

at day's end on the Texas frontier. Shown is the 1840s

Kammlah house in Fredericksburg, now maintained as part

of a museum complex by the Gillespie County Historical

Association. Photo by Susan Dial.

|

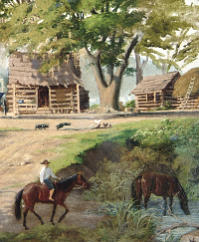

Block House, or Log Cabin, New Braunfels. Detail from painting

by early Texas artist Carl G. von Iwonski, courtesy of the Daughters of the Republic of Texas Library, Yanaguana Society Collection. Click to see full painting.

|

Hill Country frontier after 1855. |

Robert E. Lee was one of numerous

officers posted to the Texas frontier who became Civil

War generals including Albert Sidney Johnston, Earl

Van Dorn, E. Kirby Smith, George H. Thomas, John Bell

Hood, and William J. Hardee. Johnston established the

2nd Cavalry's headquarters at Fort Mason, with Lee second

in command.

|

Powder magazine at site of Fort Croghan in Burnet. The

building, used by local settlers before and after the

Civil War, is the only remaining military structure at

the site of the early fort. Photo by Susan Dial. |

|