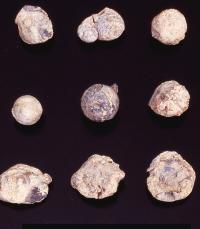

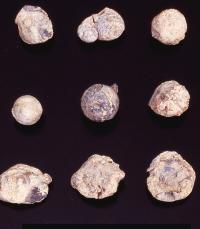

Musket balls found in the vicinity

of the church at Mission San Sabá where Spaniards

were surrounded by 2000 Wichita, Comanche, and Caddo

warriors.

|

|

Burned and shattered, the abandoned Mission San

Sabá passed into history and legend.

|

Aerial view of Presidio San Sabá

(formally, Presidio San Luis de las Amarillas) near

Menard, Texas. The presidio was partially (and badly)

rebuilt in 1936. Today the deteriorating ruins are surrounded

by a golf course. Fortunately, a broad coalition of

Menard's citizens are undertaking an ambitious restoration

program aimed at preserving the site and accurately

reconstructing enough of the fort to give visitors a

keen sense of its past. Photo by Jay Kothmann.

|

Father Alonso de Terreros, head of

the mission and cousin of "the illustrious Knight

don Pedro Terreros of the order of Calatrava,"

as the wealthy silver magnate who commissioned the painting

had himself referred to in the central text panel between

the priests.

|

|

On the morning of March 16, 1758, Mission Santa

Cruz de San Sabá, a small, hastily constructed compound

enclosed by a wooden palisade, was surrounded by 2000 hostile

Indians including Wichita, Comanche, and Caddo warriors. The

three Spanish priests in residence tried to placate the allied

native force with gifts and offers of safe passage to the

nearby Presidio, but the palisade was soon overcome and Father

Terreros, the mission leader, was killed along with several

others. A small group of people who survived the attack took

refuge in the church, the mission's largest structure. Meanwhile,

the palisade and several buildings were set on fire as the

Indians sacked the place and began celebrating victory. Sporadic

fighting continued as the Indians fired their French muskets

at the church and tried to gain entry.

Four miles upstream, the 30 soldiers at the

Presidio San Sabá heard the terrible din, saw the smoke

from the fires, and were soon surrounded themselves. While

they were able to keep the Indians at bay, the soldiers could

not come to the rescue of the mission—two-thirds of the

garrison was away on various forays. As night fell, the victorious

allied natives roasted several slaughtered oxen and feasted

a short distance from the beleaguered missionaries. While

the victorious Indians were feasting, the survivors led by

Juan Leal, escaped the burning church under cover of darkness

and made their way to the Presidio, many of them badly wounded.

The arrival of additional reinforcements (returning soldiers)

at the Presidio the next day apparently saved the garrison

from a similar fate as that of the mission.

Burned and shattered, the abandoned Mission

San Sabá passed into history and legend, illustrated

by the famous mural shown above. Presidio San Sabá

was strengthened and manned for another decade because of

its strategic role in Spanish mining operations nearby, but

then it, too, was abandoned as the Spanish frontier retreated

southward. The ruins of the presidio remained as highly visible

reminders of the Spanish presence. But the remnants of the

sacked mission, never substantial to begin with, dwindled.

Picked over time and again by souvenir hunters, it disappeared

as a known place shortly after 1900. Historians and archeologists

began trying to relocate Mission San Sabá in the mid-1960s,

but it was not until 1993 that the search met success.

This exhibit tells the story of the rediscovery

of Mission San Sabá and the archeological investigations

that followed. While some of the history of the place and

the period is presented here (see Spanish

Motives), there are many excellent historical accounts

that give more of the details (see Credits

& Sources). The story of Mission San Sabá and

its rediscovery presents fascinating lessons in how events

are viewed by history as well as the interplay between history,

archeology, and luck.

The archeologist who narrates the remainder

of this exhibit is Dr. Grant D. Hall, Associate Professor

of Anthropology at Texas Tech University. Born and raised

in Texas, Hall has carried out numerous archeological investigations

in the coastal plains, south and central Texas, and the Maya

Lowlands. Since 1990, he has taught at Texas Tech and involved

his undergraduate and graduate students in an ambitious regional

research program centered on the San Sabá River valley.

Every summer a Texas Tech field school is held in the region,

usually at localities between Menard and San Sabá,

Texas. The students always get a good basic training in archeological

field methods as well as the chance to help uncover San Sabá

history and prehistory.

Today Hall is joined at Texas Tech by Dr. Tamra

Walter, a specialist in historical archeology. They and their

students are excavating Presidio San Sabá to reveal

more of its history and obtain the evidence needed for a historically

accurate reconstruction. They enjoy the strong support of

the people and civic leaders of Menard who hope to make the

Presidio a focal point for tourism and history.

"The Destruction of Mission San Sabá"

The famous mural was painted in Mexico City,

perhaps in 1765, about 6 years after the mission was destroyed.

The painting was commissioned by Don Pedro Romero de Terreros,

cousin of one of the first priests killed in the attack. Terreros

had made a fortune in mining down in Mexico and put up the

money to finance the Mission San Sabá. Though the artist

was never in central Texas, he was advised by eyewitnesses

as to the appearance of the mission and the details of the

Indian attack. A careful examination reveals that the mural

tells the story of the attack, including the fates of the

two priests who were killed. The blue shields beside each

priest contain their biographical sketches.

Archeological findings at the mission confirm

that the mural is fairly accurate. The houses, church, and

stockade were built of wooden posts and poles. The roofs were

thatch. This building technique is known as wattle-and-daub

in English. In Spanish, the method is known as jacal (pronounced

HAH-call), and it is still in use in Mexico and other Latin

American countries. In addition to the mural and verbal descriptions

of how the mission looked, we have fired clay daub and post

stains uncovered at the site to provide further evidence of

the size and configuration of the mission compound and the

methods used in its construction.

The mural is thought to be the earliest painting

by a professional artist depicting an historical scene in

Texas. It is still in the possession of Terreros family descendants

in Mexico. The family shipped the mural to the United States

for sale in the early 1990s. Controversy ensued and the Mexican

government claimed the mural as national patrimony. It was

returned to Mexico.

|

Remnant of burned post that once

formed part of the mission walls.

Click images to enlarge

|

|

As night fell, the victorious allied natives roasted

several slaughtered oxen and feasted a short distance

from the beleaguered missionaries.

|

Historical Marker at Presidio San

Sabá.

|

Dr. Grant D. Hall, leader of the

archeological investigations at Mission San Sabá.

Here he poses at the ruins of Presidio San Sabá

along with several of his students. Photo by Mark Mamawal,

Texas Tech Univeristy.

|

The priests in the mural are depicted

in gruesome detail showing the manner of their death.

The blue shields beside each priest contain their biographical

sketches.

|

|