Contour map of Hinds Cave showing the areas of excavation for the 1975 and 1976 seasons.

|

Close up of stratigraphic deposits dating to over 6,000 years ago in a latrine area (Block B) in Hind Cave. The lumps at the top are coprolites and below this are fine lenses of fiber and fine sediment compacted by the use of this area as a latrine. This kind of preservation is extremely rare in most archeological deposits. TAMU Anthropology archives.

|

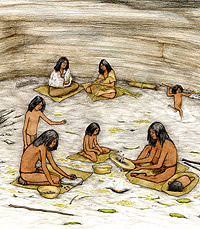

Artist's rendering of a family group at work and play at Hinds Cave during the Archaic era. Illustration by Peggy Maceo.

|

View of the bottom of the side canyon housing Hinds Cave. TAMU Anthropology archives.

|

This exposed fiber lens illustrates the remarkable degree of preservation in plant materials in the upper portion of Block A. TAMU Anthropology archives.

|

|

This dry rockshelter on a small side canyon of the lower Pecos River in southwestern Texas proved to be a veritable scientific treasure chest, yielding dried organic bits and artifact pieces telling the story of over 9,000 years of hunter-gatherer life. For generation after generation, native peoples of the region periodically stopped at Hinds Cave. Following a lifestyle uniquely suited to the Lower Pecos Canyonlands, theirs was a highly mobile existence, moving from place to place through an area where nature’s harvest is seldom bountiful—the northeastern edge of the Chihuahuan Desert. They were adept at taking advantage of an astonishing variety of plants and animals. Their diet was high-fiber, low-fat, varied, and included most anything that “wiggled, squiggled, or crawled” as one researcher put it. Although living conditions were often challenging and sometimes downright harsh, the traces they left behind are those of an incredibly durable cultural tradition that spans at least 9,000 years of prehistoric time, from before 8,000 B.C. to about a thousand years ago or perhaps a bit longer.

Like most dry rockshelters in the Lower Pecos Canyonlands, Hinds Cave has been dug into many times by artifact collectors since the 1930s. Fortunately in the mid-1970s an interdisciplinary research team from Texas A&M University carefully excavated a small portion of the site and collected a wealth of perishable scientific treasure. Not gold or silver, but unusually well preserved fragments of ancient life—fiber artifacts such as worn-out sandals, discarded plant and animal food refuse, grass-lined beds the site’s occupants once curled up in to sleep, and much more. Surprisingly, scientists have learned the most from what they found in ancient latrines along the back wall of the cave—hundreds of desiccated human feces or coprolites. Processed carefully and studied under the microscope, this residue has yielded remarkable insight into the diet and health of the small family bands who occasionally stayed overnight in Hinds Cave.

Student and volunteer-based research teams investigated the site during two major field seasons in the summers of 1975 and 1976 led by two professors of anthropology at Texas A&M, Harry J. Shafer and Vaughn M. Bryant. The research was designed to take advantage of the marvelous preservation conditions to study the paleoecology and daily lives of the people who once inhabited the site. The remarkably dry and intact deposits offered an opportunity to examine the plant material utilized for food and raw materials, preparation methods for foods, tools used in their everyday lives, living conditions at the site, and most importantly, a direct study of their diet.

Previous investigations in the Lower Pecos Canyonlands had not taken full advantage of the incredible scientific potential of the dry cave conditions that were once prevalent in the region. By the end of the 20th century, most of the dry shelters had been plundered by relic hunters or had disappeared beneath the waters of Amistad International Reservoir. Both Shafer and Bryant had been involved in the 1960s Amistad salvage program and had recognized the lost research opportunities (for background, see Before Amistad).

In 1973 an undergraduate student brought a box of perishable artifacts into Harry Shafer’s office at Texas A&M in College Station and asked the professor what he thought. In the box were sandals, basketry fragments, twisted cord, and various other organic materials including a coprolite that the student, Fred Speck, had dug up in a dry cave some 600 miles to the west. With Speck’s help, Shafer and Bryant secured permission from the landowner, Carrol W. Hinds, to carry out archeological research and the Hinds Cave project was launched. They hoped to overcome some of the shortcomings of the previous research and provide substantial new information on the lives of the Archaic period hunting and gathering peoples on the northern edge of the Chihuahuan Desert.

In This Exhibit

In this exhibit readers can learn more about the research at Hinds Cave and the scientific treasure the site yielded, most of it collected as bag after bag of dried plant remains, coprolites, and dirt. The scientific payoff has taken decades to realize and several laboratory-based research projects are still underway.

In the first section, explore the Natural Setting of Hinds Cave and its immediate surroundings. Those who lived here took advantage of the resources found nearby in the canyon, the river, and on the uplands as well.

The Paleoclimate section sketches the climatic changes over the last 25,000 years, before and during the periods in which people used Hinds Cave. These first two sections essentially set the stage.

Explore Hinds Archeology is a special exhibit section loaded with information and images. Readers can use interactive maps of the site to explore photographs of the dig and learn about each of the excavation areas. The “Essentials” provide topical summaries of the essential archeological details, from dating and stratigraphy, to logistics and a gallery of field photos.

The Artifacts section illustrates the unusually well preserved material culture found at Hinds Cave and uses the broken and discarded things that people left behind to tell about the lives of those who visited the site.

Life at Hinds summarizes the remarkably successful way of life that persisted for more than 350 generations and the native peoples who stopped now and again to spend a few days at a dry rockshelter in a side canyon off the lower Pecos River.

In Kids section, viewers young and old can solve an ancient mystery with Dr. Dirt, the armadillo archeologist .

In Teaching, school teachers can download a lesson plan that will help children contrast their own lives with ancient life in Hinds Cave.

Credits & Sources acknowledges those who contributed to the work at Hinds Cave and those who created this exhibit. The Hinds Cave bibliography lists virtually all of the published sources that serious students of archeology can consult to learn more about Hinds Cave. |

Excavations and recovery are in full swing during the 1975 season. Note dust from screening and use of face masks. Dust is a constant problem in dry cave investigations. TAMU Anthropology archives. |

Cave, Shelter, or Rockshelter?

Technically, Hinds Cave is a rockshelter because it is much wider (120 feet) than it is deep (75 feet). The small alcove at one end of the shelter is a true cave, but not much of one. While most of the “dry caves” of the Lower Pecos Canyonlands are really rockshelters (or shelters in shortened form), locally they are known as “caves.” A distinction perhaps without a difference, all three names are used interchangeably in this exhibit: cave, shelter, and rockshelter.

|

Excavation are in progress during the 1976 season. Students Michael Boon and Kenny Hatfield are in the foreground. TAMU Anthropology archives. |

One of the first coprolites found by archeologists at Hinds Cave during initial testing of the site in 1974. With this find, the Texas A&M researchers knew they had hit “pay dirt.” Studies of Hinds Cave coprolites have revealed many details about the diet and life of the cave’s inhabitants. Photo by Glenna Williams-Dean. |

Portion of knotted netting and twisted cordage from Hinds Cave TAMU Anthropology archives.

|

Artist's depiction of a camp in the uplands such as the terrain overlooking the Hinds Cave canyon. The brush shelters may look flimsy, but they were mainly needed to create shade from the intense sun. The woman in the foreground is trimming sotol leaves, perhaps to use them for weaving a new sleeping mat. Painting by George Strickland, courtesy Witte Museum of San Antonio. |

|