Long-leaf pine, one of the

several varieties of trees harvested by loggers

in East Texas.

|

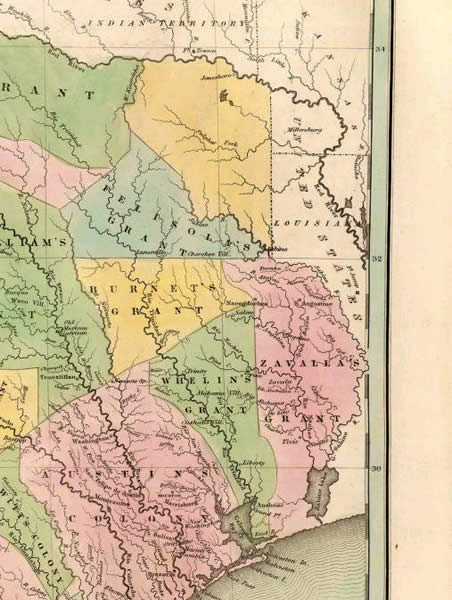

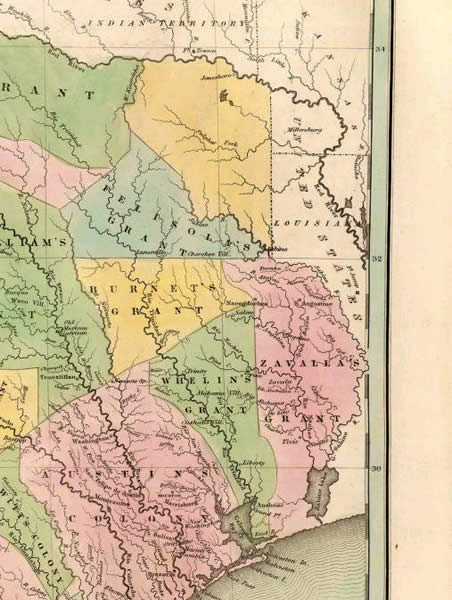

Land grants

in East Texas, circa 1838. In

Texas Republic days, land was

an attractant for settlers and

brought cash to the treasury.

In the decades following, vast

timber-laden tracts were accumulated

for lumber operations. Map by

Thomas G. Bradford, courtesy of

David Rumsey Historical Map Collection.

Click to enlarge.

|

Tall pines

stand sentinel at an old farmstead

south of Lufkin in East Texas.

Early settlers made only small

inroads into the vast forests,

building log cabins and farm buildings

and clearing fields for crops

and grazing. Photo by J. Griffis

Smith, courtesy Texas Parks and

Wildlife. Click to enlarge.

|

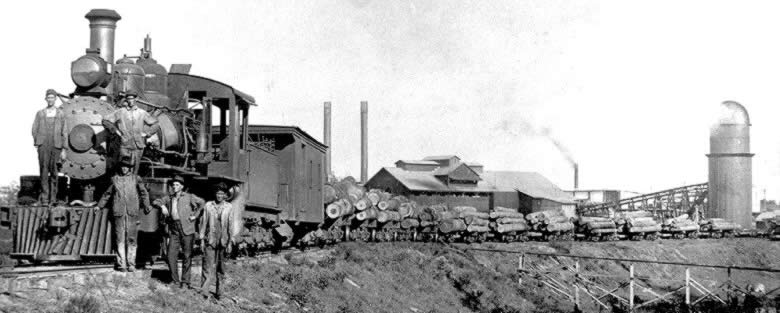

Thompson Lumber

Company office in Houston. What

was to become one of the major

lumber operations in East Texas

began in 1852 with John M. Thompson's

establishment of a small mill

in northern Rusk County. Photo

courtesy Stephen F. Austin State

University, Thompson Collection.

Click to learn more.

|

|

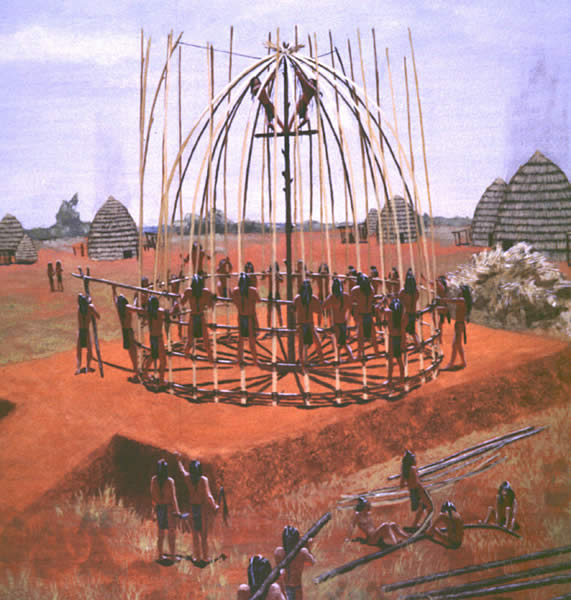

Settlers coming into East Texas in the

early 1800s encountered vast forests—pines and

hardwoods extending for miles in a verdant swath broken

only by murky, meandering rivers. Caddo Indians had

lived in these woodlands for thousands of years, felling

trees for their tall, beehive-shaped houses and temples

and constructing villages along the Red River, Neches

and Sabine. But their impact, and that of the Anglo

farmers who followed them, was light, and the forests

maintained their dominance on the land.

Commercial logging was

to alter that balance, and in the process

bring tremendous changes in the economic,

social, political, and environmental

composition of the region. Evolving

from small water-powered mills to massive

sawmill complexes and factory towns,

the logging business became the primary

focus of activity in the region and

lumber the lifeblood for various support

industries, from ports, railroads, equipment

suppliers, and mercantile companies

to family farms that supplied produce

to the growing sawmill communities.

Lumber Shortage

Amid Forests of Plenty

On March 1, 1836, Texas declared its independence

from Mexico and, through armed revolution, won its independence

on May 12, 1836. As a fledgling nation, Texas was without

any financial structure. In order to develop a treasury,

Texas sold its only commodity—land. This process

stimulated land entrepreneurs, or speculators, to treat

land as cash. Frequently a land grant was sold several

times prior to actual survey. Some people began to acquire

enormous landholdings, a factor that attracted corporate

investment in large sawmill operations several decades

later.

The first sawmill identified

with a specific individual is an 1829

mill on Carrizo Creek in Nacogdoches

County, built by entrepreneur and land

speculator Peter Ellis Bean. Bean exemplifies

the nature of the American frontiersmen

who settled Texas. He first entered

Texas in 1801, hunting horses and trading

with Indians along the Brazos River,

at a time when it was still under Spanish

rule. He built a water-powered, sawmill

(sash saw) and gristmill and also ran

a lumberyard in Nacogdoches. Attracted

by that success, other logging entrepreneurs

began operations in Texas.

In the decades before the Civil War, however,

transportation was a continual problem. Due to the natural

obstacles of rivers and muddy soils, few overland roads

were suitable for travel at all times, particularly

in East Texas. Rivers, which formed the backbone of

commerce in the United States, were erratic in water

flow and became clogged with logs, snags, and silt.

Sawmill owners in the East Texas interior were forced

to settle for local trade combining a grist mill and/or

general merchandise store, while coastal lumbermen had

developed a considerable export trade worldwide.

The centers of commerce

developed along the Gulf Coast, where

marine shipping could interface with

riverine steamboats and overland wagon

haulers. Logging rafts, keelboats, and

later steamboats operated only during

optimal river flow conditions. Due to

this lack of transportation, the vast

pine forests of East Texas could not

be fully exploited in a profitable manner.

Consequently, despite the abundance

of standing timber, there was a chronic

shortage of lumber within Texas.

The Bonanza

Period: 1876-1917

|

|

In this section:

|

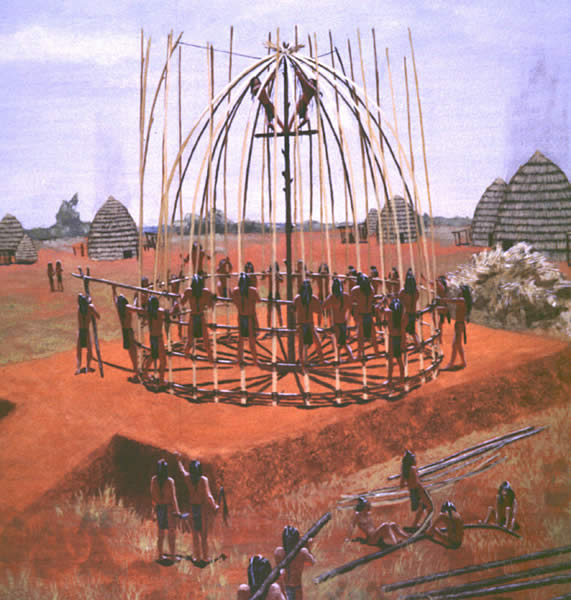

Caddo Indians, the first settlers

in the Piney Woods, used poles made from young

pine trees to construct their houses and temples.

In this artist's depiction of a scene around 800

years ago, teams of Caddo builders set tall, flexible

poles in a circular frame for a large, dome-shaped

house. Painting by Nola Davis, courtesy Texas

Parks and Wildlife Department, Caddo Mounds State

Park. Click to enlarge.

|

The Great Raft, a massive logjam

in the Red River. Natural obstacles such as this

blocked transportation on rivers in East Texas,

heightening the need for improved transportation

on land. Photo courtesy of Louisiana State University,

S. Noel Collection.

|

|

The logging business became

the primary concern in the region

and lumber the lifeblood for various

support industries, from ports,

railroads, equipment suppliers

and mercantiles to family farms

that supplied produce to the growing

sawmill.

|

|

|

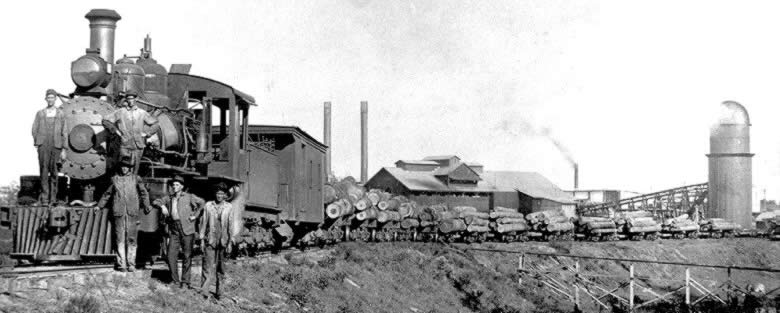

Texas and South-Eastern Railroad log train

at Diboll, circa 1910. The completion of a railroad network

in East Texas and across the state—enabling transport

of wood products from forests to mills and beyond—was

a key factor fueling the Bonanza Period of logging. Photo

courtesy The History Center, Diboll.

|

Henry J. Lutcher.

The lure of land drew the Pennsylvania

lumberman and his partner, G.B.

Moore, to Texas in the 1870s.

Lutcher and Moore constructed

a "state-of-the-art" sawmill at

Orange and purchased timberland

on both sides of the Sabine River.

The two later built three railroads:

the Gulf, Sabine, and Red River;

the Mississippi and Ponchartrain;

and the Orange and Northwestern.

|

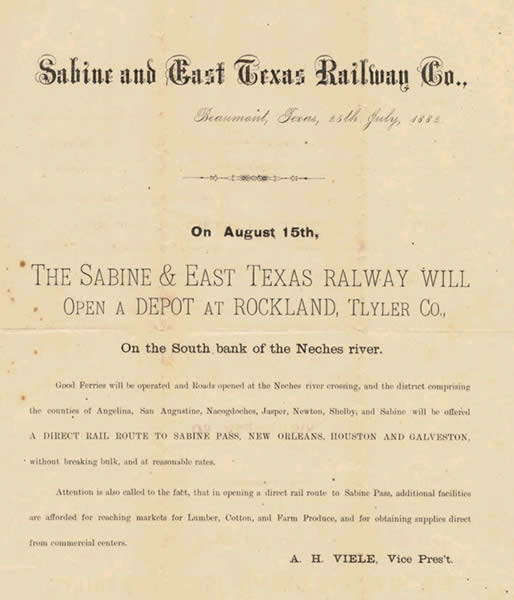

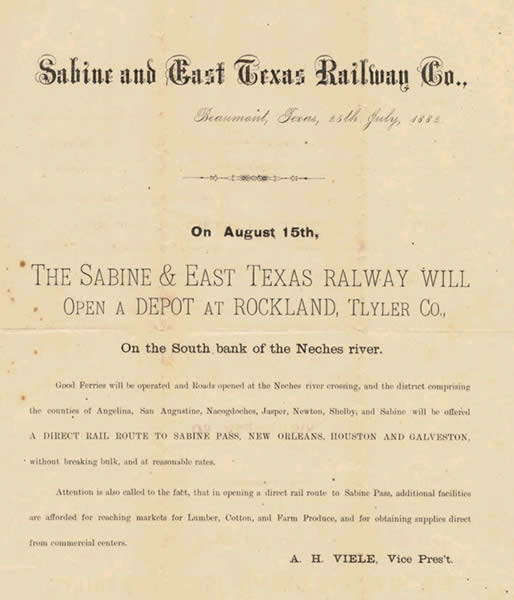

Flier for the

Sabine & East Texas Railway, 1882.

The company, later incorporated

into the Texas and New Orleans

line, was one of many short, trunk

lines constructed by mill owners

during the Bonanza period to move

lumber products. Photo courtesy

"Texas Tides" digital historic

photo collection, Stephen F. Austin

State University. Click to enlarge.

|

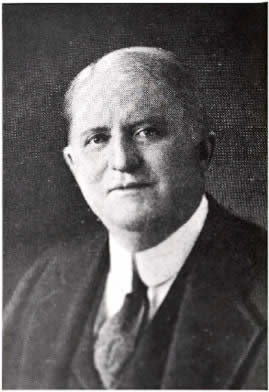

Thomas Lewis

Latane Temple (1855-1935) founded

Southern Pine Lumber Company in

1893, Texas South-Eastern Railroad

in 1900, and Temple Lumber Company

in about 1906. The Southern Pine

and Temple companies merged in

1956 and are now known as Temple-Inland

Forest Products Corporation. Photo

courtesy of The History Center,

Diboll.

|

|

The Civil War halted settlement

and economic growth in East Texas. Investment

in transportation began again after

the war, particularly due to the liberal

policies of the State, which granted

land to rail companies for each mile

of track they lay. By 1880, railroad

development had reached a point where

main lines connected most of East Texas.

At this time a new innovation, the band

saw, also arrived, enabling safer and more efficient

milling operations. Concurrently, the forests of the

Great Lakes were being cut out, and investment capitalists

were turning their attention to the forests of the south,

and Texas in particular. This marked the beginnings

of an enormous period of growth for Texas logging and

the rise of the big mills. Again, land speculators combed

through the courthouses and land districts of East Texas,

acquiring lands that were unclaimed or available for

back taxes and putting together some of the largest

tracts to date in Texas.

In "Sawdust Empire," Robert

S. Maxwell and Robert D. Baker describe this period,

ranging roughly from 1876-1917, as the "Bonanza

Period" of the logging industry in East Texas.

It was during this period that fortunes (both personal

and corporate) were made. The larger mills that had

been established earlier in the period grew larger and

more powerful, while many of the smaller mills as well

as some of the large mills that had come too late into

the region, suffered from a lack of access to timber

and were forced out.

The Bonanza Period of industrial logging

would never have occurred were it not for the introduction

of the railroad to the forests of East Texas in the

1880's. Prior to that time, transporting cut timber

to the mills was a slow, tedious endeavor dependent

upon draft animals, good weather, and good fortune.

Initially logging was performed close to rivers, where

water was used to ship the cut and seasoned logs to

the mill. Staging areas were located at central areas.

The logger cut the trees with an ax, using a saw to

cut the tree to lengths. The trees were dragged by oxen

or mule to the river bank where they were stacked awaiting

high water. Once in the water the logs were joined into

rafts, and floated to coastal mills.

The advent of steam-powered,

small-gauge trains and loaders made

it possible to transport ever larger

loads of logs to the mills. Once the

railroad was extended into the interior,

mills were constructed closer to the

remaining virgin stands. Corporations

built much larger mills along rail spurs

in the remaining uncut areas of East

Texas.

In the Woods

Trees were selected, felled,

scaled, and cut to transportable size

by timber crews , usually 40 to 60 men

supervised by a woods boss, known also

as the "bull of the woods."

Conditions were often grueling, with

workers putting in 10-hour days on back-breaking

tasks in the forests, often many miles

from the mill. Many experienced loggers

were expert at their trade, able to

notch, saw, and fell a tree with precision.

In addition to cutting tasks, forest

workers transported logs, worked on

roads, and set miles of ties for rail

tracks.

|

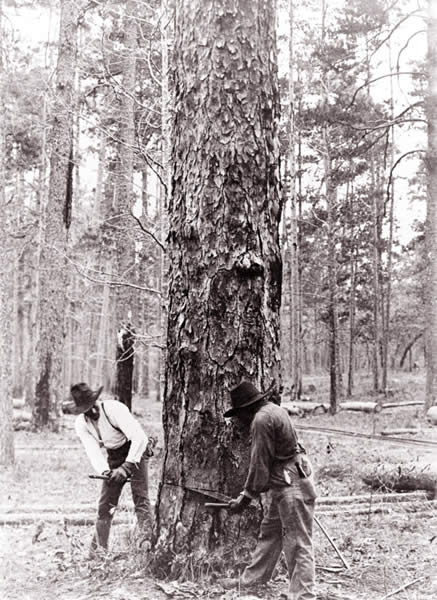

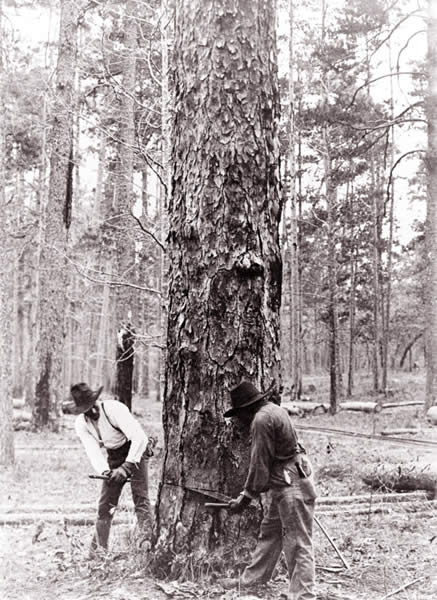

Two sawyers

use a crosscut saw to cut down

a large pine. Photo courtesy Center

for American History, University

of Texas at Austin. Click to enlarge.

|

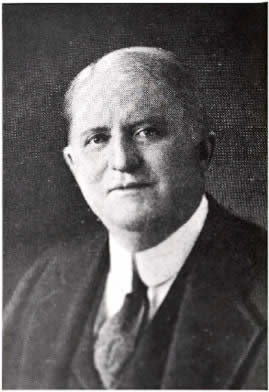

John Henry

Kirby, the "Prince of the Pines,"

shown in a 1925 photo. Kirby built

a railroad, oil company, and lumber

company, at one point controlling

more than 300,000 acres of land,

but was forced into bankruptcy

during the Depression. Photo courtesy

of the Center for East Texas Research,

Stephen F. Austin State University,

Forest History Collection. Click

to learn more.

|

|

|

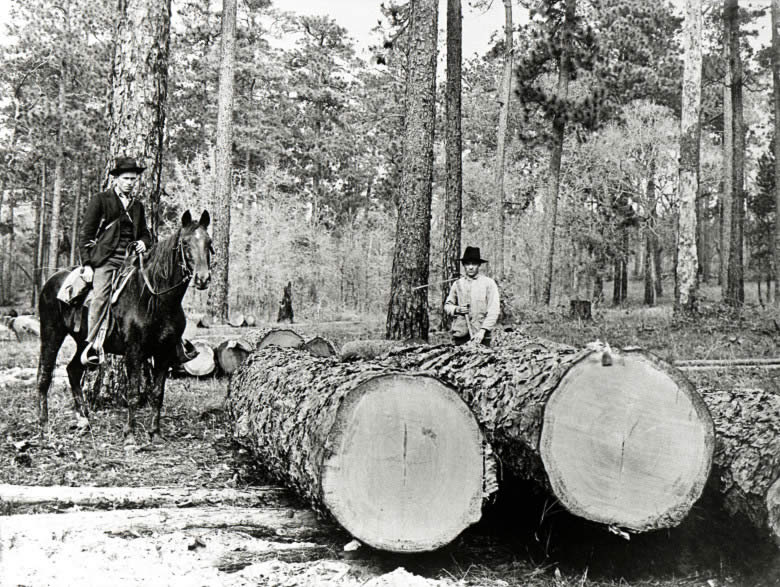

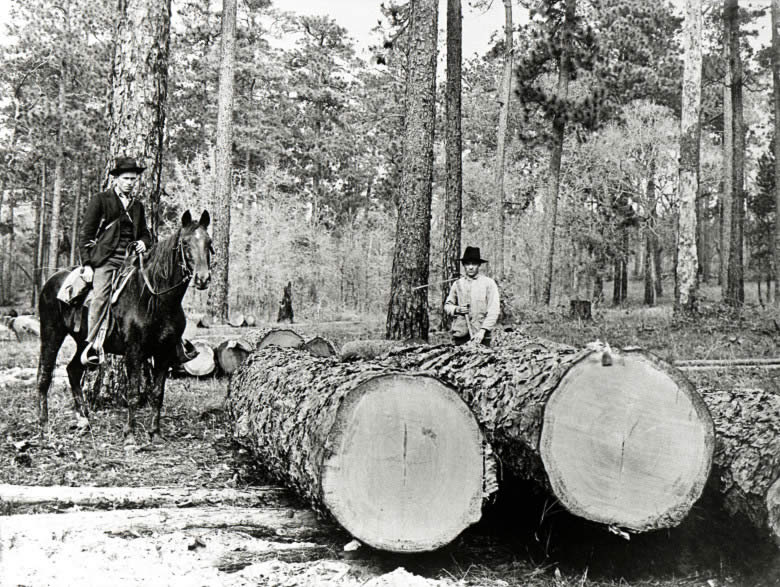

"Buckers,"

or choppers, saw pine trees, which

have been stripped of branches, into

smaller sized-logs for transport.

Photo, circa early 1900s, courtesy

of Center for American History, UT-Austin.

Click to enlarge.

|

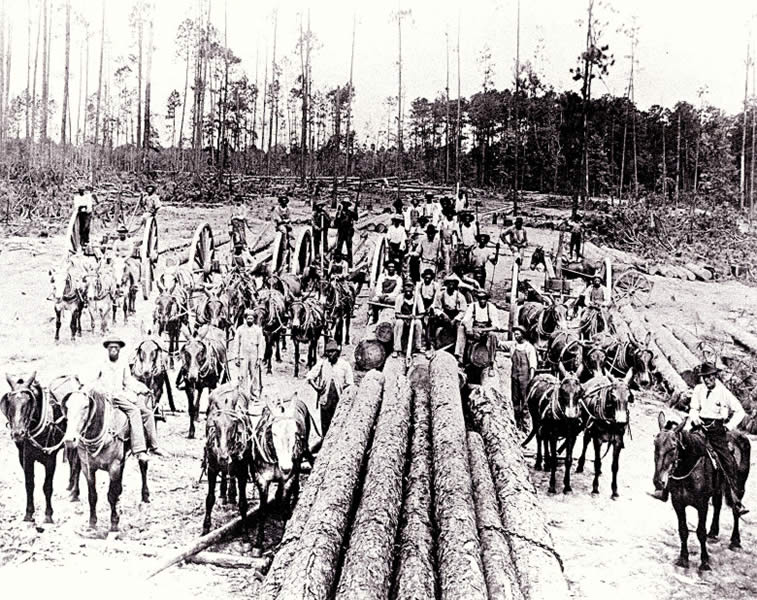

The woods boss,

or "bull of the woods,"

looks on as a scaler evaluates the

size of a log. The boss wielded considerable

authority: when a worker got into

a confrontation with the boss, it

was said that he had "locked

horns with the bull." Photo,

courtesy of Center for American History,

UT-Austin. Click to enlarge.

|

An enormous log

is loaded on a high-wheeled cart,

ready to be pulled by mules to a flatcar

for transport to the mill. Photo,

courtesy of Center for American History,

UT-Austin. Click to enlarge.

|

|

|

Logging workers, hauling

hundreds of yards of cut timber, emerge from a partially

cut forest in East Texas. Photo courtesy Center for

American History, UT-Austin. Click to enlarge.

|

Early cross-loading

operation using mules to haul logs onto a flatcar. The

later introduction of steam-powered cranes to hoist

the logs revolutionized the logging industry. Photo

courtesy Center for American History, UT-Austin. Click

to enlarge.

|

|

Mills and Mill Towns

|

A train carries a load

of logs to the Thompson Brothers mill. The

logs were floated into the mill pond for storage

or guided by a "pond monkey" onto a chain

and into the mill for processing. Photo courtesy

of Center for American History, UT-Austin,

East Texas Photograph Collection, (DI#01287).

|

Workers stand

by as logs pass down a conveyor

belt in this early 20th-century

sawmill. Photo courtesy of USDA

Forest Service. Click to see full

image.

|

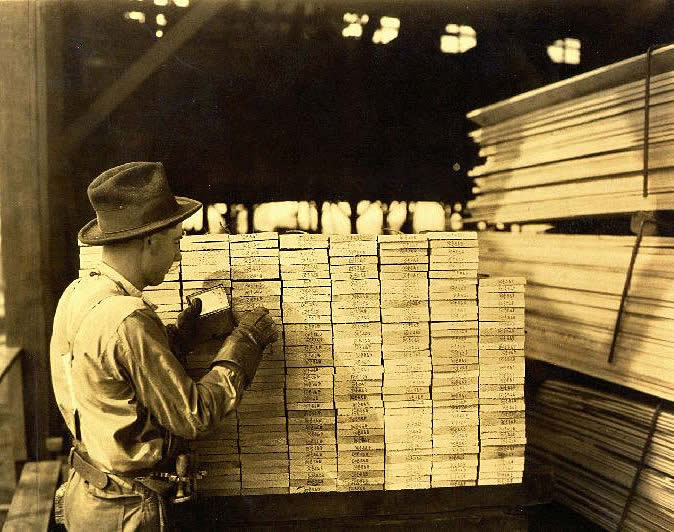

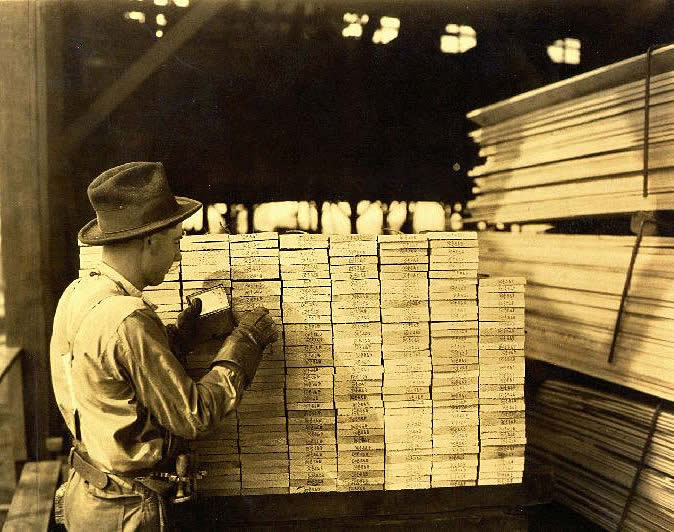

A sawmill worker

checks a load a lumber ready for

shipping. Photo courtesy of Stephen

F. Austin State University, Forest

History Collection.

|

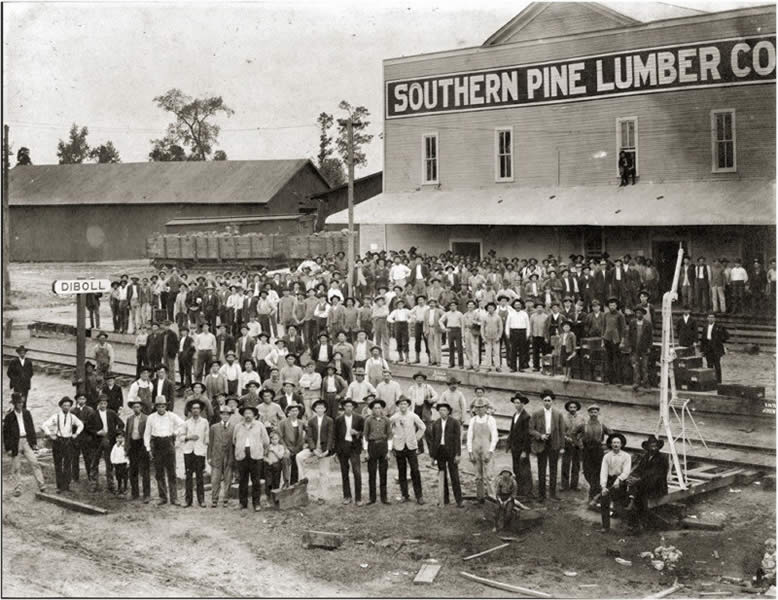

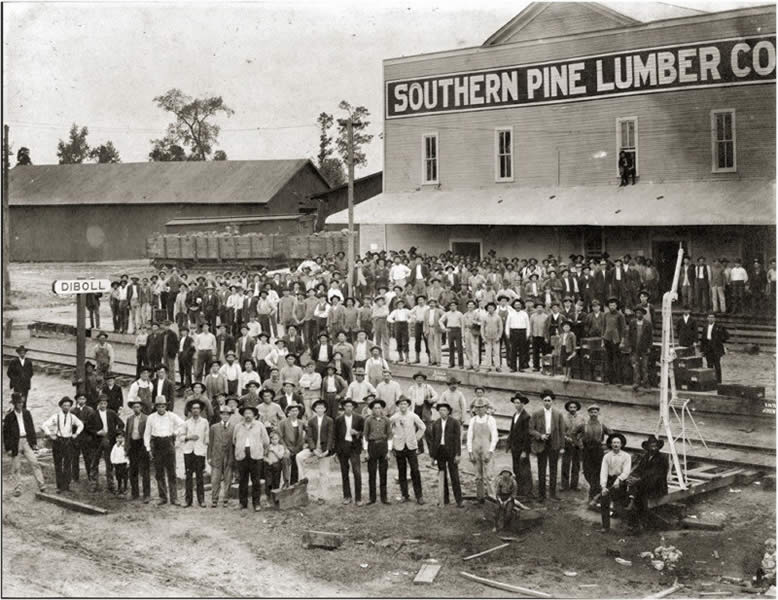

Employees of

the Southern Pine Lumber Company

in front of the company store,

or commissary at Diboll, about

1907. Photo courtesy of The History

Center, Diboll.

|

Children walk

along the railroad tracks at the

Diboll sawmill ponds in about

1912. Their parents were managers

at the Diboll commissary and the

planing mill. Click to enlarge.

Photo courtesy of The History

Center, Diboll.

|

|

During the Depression, the

Southern Pine Lumber Company was

forced to sell about 100,000 acres

for less than $3 an acre to keep

its sawmill working. Many Diboll

employees repaid the loyalty the

company had shown them by lending

the company small sums of money

they had managed to save.

|

A "front camp"

in the forest. Wood crews-flatheads,

skidders, loaders, and others--often

worked miles away from the sawmills,

making it necessary to set up

temporary living facilities for

workers and their families. Small

towns of tents or boxcars were

common in the woods. Photo courtesy

of Stephen F. Austin State University,

Thompson Collection. Click to

enlarge.

|

|

By 1910 there were more

than 600 sawmills in Texas, although

probably no more than 100 could be considered

large mills—those with a capacity

of 80,000-100,000 board feet. In many

areas, the sawmill represented the only

source of cash, and two or three generations

often worked in turn at the mill. The

mill created work where none had been

available, and the owners had to provide

housing, usually deducted from pay.

In terms of operations,

one of the most important features of

the mill was the mill pond. It covered

several acres and could hold up to four

million board feet of logs. The water

provided ease of loading and unloading,

preserved the logs from bark beetle

attacks, and washed dirt and soil off

the logs, thus reducing wear on the

saws. From the pond, the logs were moved

onto a conveyor chain, and were hauled

to the log deck. If no pond was available,

rail tracks were placed as a siding

as close to the saws as possible.

A typical large sawmill

was a complex of two or three story

buildings divided according to each

step of the lumber-making operation.

The saw machinery usually was located

on the second floor, the saw filer,

who kept the saws sharpened, on the

third floor. On the second floor, the

scaler measured and sized the log, using

the cutoff saw to section the long timber

into efficient cutting lengths. Moved

via a log kicker, logs were then sent

to bandsaws, where the sawyer cut the

log into boards. Once trimmed, the lumber

was transported into the yard to dry

and cure before it was finally sent

to the planer for final processing.

With the growth and expansion

of mills came company towns, the small

communities which were to dominate the

landscape and economy of East Texas.

The company town typically was isolated,

placed near the critical resources—large

tracts of timber. As trees were cut

down and forests used up, logging operations

moved into more-remote areas, and more

towns built. It was not uncommon for

towns of a thousand people or more to

spring up in a year's time.

Mill towns were composed

of segregated groups of houses for black

and white workers and their families,

a general store or commissary, a hotel/boarding

house, company offices, churches, schools,

and stores. In most towns, water was

pumped from a well for two or more houses;

indoor plumbing and electricity became

available in some areas in the late

1920s. Most homes had gardens and a

few chickens kept in pens or ranging

free in the yards. Wood cook stoves

and potbellied stoves provided heating

and served for food preparation.

Mill towns varied as to

amenities and comforts. While Fostoria,

a milltown owned by the Foster Lumber

Company of Kansas was described as clean,

well-kept, and self-sustaining, Kirbyville,

owned by the Kirby Lumber Company, was

characterized by a visiting Harper's

Weekly journalist as "gray

dingy boxes arranged row by row in the

horror of dull uniformity that is the

curse of most industrial communities."

Generally, the larger and more influential

mill owners, such as Lutcher and Moore,

T.L.L. Temple, the Thompson Brothers,

and Carter-Kelly companies, were responsible

for the more well developed and advanced

mill towns, with electrical power and

running water available to most, if

not all, mill town residents.

In some towns, deep bonds

were formed between company and workers.

During the Depression, the Southern

Pine Lumber Company was forced to sell

about 100,000 acres for less than $3

an acre to keep its sawmill working.

Many Diboll employees repaid the loyalty

the company had shown them by lending

the company small sums of money they

had managed to save.

In addition to mill towns,

the East Texas forests were dotted with

temporary camps and make-shift towns

for the workers in the woods—those

involved in cutting and harvesting trees

and making wood products. There were

front camps, often constructed along

rail trams as staging areas for workers;

turpentine camps, where pine resins

were harvested and made into turpentine;

tie camps where railroad ties were collected

and shipped; stave camps, where barrel

staves were made; tent camps along railroads

or in remote settings; and the cutting

front itself. Boxcars and tents typically

served as housing for the forest workers.

These facilities were

usually established next to the main

lines of the logging railroads, which

connected them with the primary mill

and its mill town. These logging railroads,

or trams, provided not only the principal

means of carrying cut timber to the

mill, but also functioned as a basic

transportation system for the front

camp workers, who usually had families

living in the primary mill towns. These

trams were extended as the logging fronts

advanced through the virgin pine forests,

often resulting in an intricate spiderweb

design of cleared routes that would

eventually become the basis for a fully

developed rural transportation system

of Farm-to-Market and County Roads.

Without this infrastructure, the modern

development of East Texas would not

have been possible.

After the Boom

|

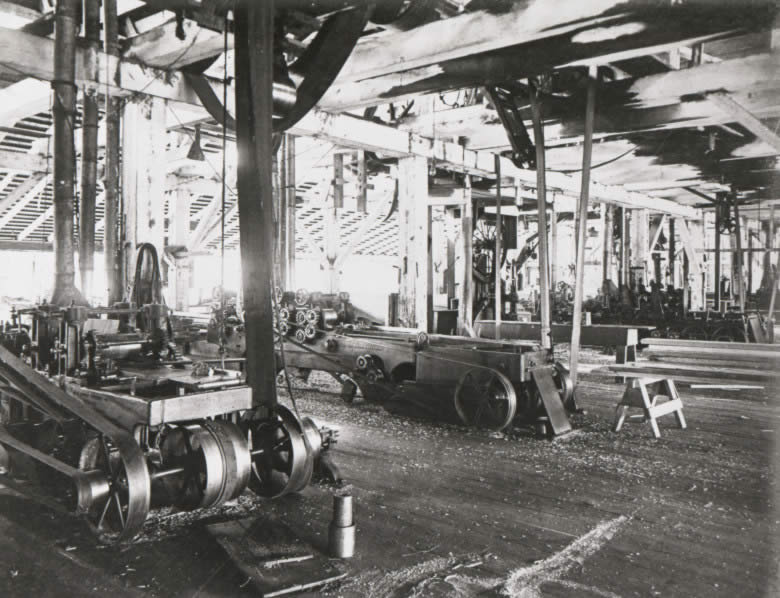

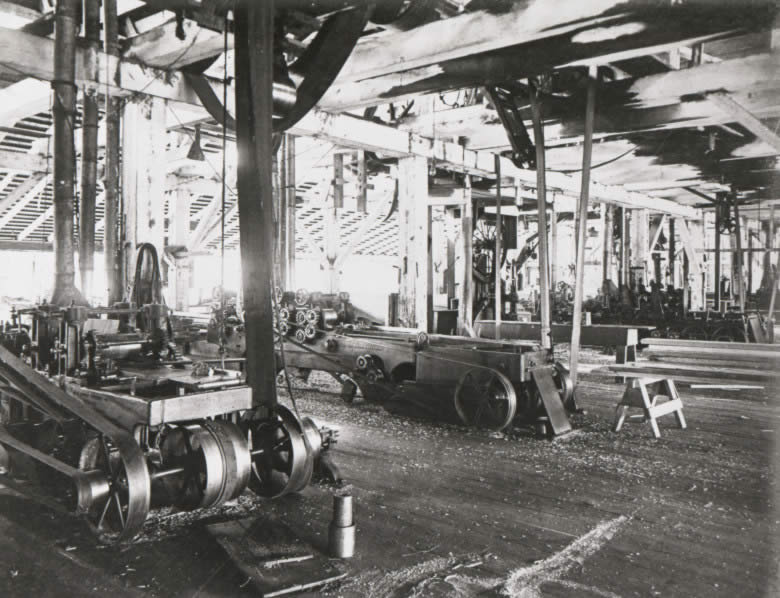

Interior of

an early 20th-century sawmill.

Photo courtesy Center for American

History, University of Texas at

Austin. Click to see full image.

|

Lumber planks

are loaded into boxcars for distribution

in this 1907 scene at the Diboll

mill. Photo courtesy of The History

Center, Diboll.

|

A family poses

on the front porch of their company

house in a milltown. Housing provided

by lumber companies varied from

town to town; this board-and-batten

cottage would have been considered

quite comfortable. Click to enlarge.

Photo courtesy Stephen F. Austin

State University, Forest History

Collections.

|

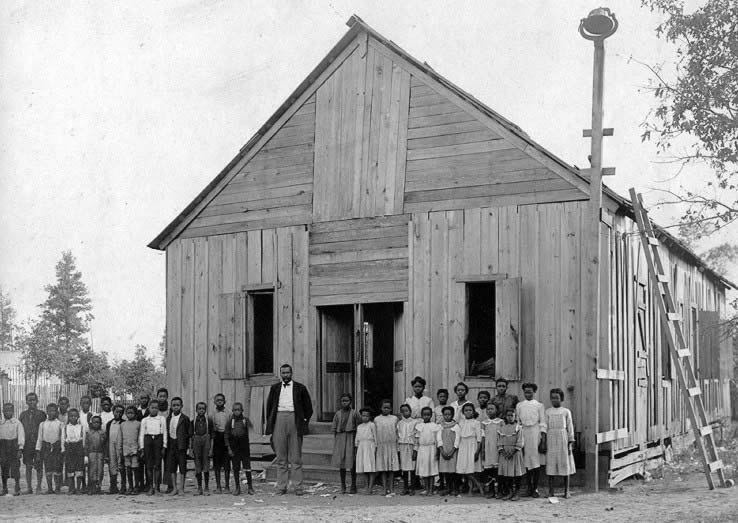

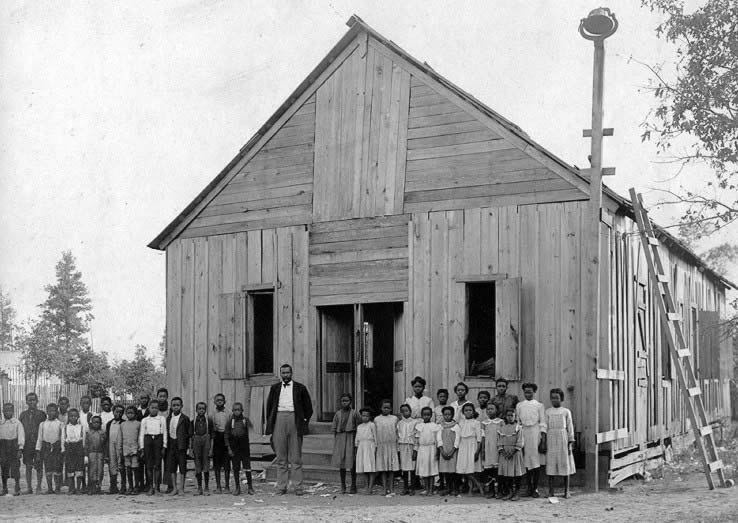

Pupils gather

with their teacher in front of

the Diboll school house, circa

1907. Many milltowns had both

segregated schools and residential

areas. The teacher in the photo

is identified as J.W. Hogg. Photo

courtesy The History Center, Diboll.

|

A child poses

on the cowcatcher of Temple Lumber

Company train engine No. 6, with

its crew. Transporting both logs

and timber workers from forests

to milltowns, trains and forest

trams were a vital connection

for the logging business in East

Texas. Photo courtesy of The History

Center, Diboll.

|

|

|

Tree stumps dot the rolling

landscape where tall pines once stood. Since

the time of this circa 1902-1908 photo, much

of the deforested land has been purchased

by the USDA Forest Service and replanted.

Photo courtesy of the center for American

History, UT-Austin (#DI-01295).

|

William G. Jones, a banker

from Temple, Texas, helped establish Arbor Day

and The Texas Forestry Association with the purpose

of replanting trees. He later petitioned President

Franklin Roosevelt for forest and wildlife reserves

on cutover lands, an effort which led to the National

Forests in Texas. Photo courtesy of Stephen F.

Austin State University, Forest History Collection.

|

A branch of

a young pine tree. Trees planted

by the USDA Forest Service and

East Texas lumber companies in

cut-over areas have grown into

mature forests in many areas.

Photo by Elizabeth Grivas, courtesy

of Texas Department of Transportation.

|

|

In 1917, Robert W. Wier

and the Lutcher and Moore heirs combined

resources to construct the last large

mill at the town of Wiergate, with timberlands

covering about 86,000 acres in Newton,

Jasper, and Sabine counties. The Wiergate

Lumber Company logged what was perhaps

the last great Texas stand of longleaf

pine.

By 1920, many of the lands

acquired by the big mills had been cut

out, leaving tangled thickets of second

growth hardwoods, mixed with a few pine

seedlings. Foresters and conservationists

complained that the practice of free-range

husbandry eliminated pine regeneration

and promoted the growth of hardwood,

thereby eliminating the potential for

sustained yield logging. Some companies

moved to the West Coast, where large

tracts of lands and forest were available

to sustain the cut-and-run method of

logging. Others went bankrupt, letting

their lands fall into receivership.

Because Texas had retained

its public lands when it became a state

in 1845, the federal government lacked

national parks and forests in the state.

In May 1933, the Texas legislature passed

a bill, supported by both lumbermen

and conservation groups that authorized

the U.S. Forest Service to appraise

and purchase lands. The federal government

purchased more than 90% of the lands

that were to comprise the National Forests

in Texas from 11 lumber companies.

Beginning in 1898, the

Forestry Bureau of the U.S. Department

of Agriculture began an agreement program

with Texas lumber companies and private

individuals to develop working plans

to restore the forests and develop a

sustained yield strategy. From the 1930's

to the present, the U.S. Forest Service

has replenished the East Texas forest

reserves and developed effective sustained

yield practices, while conserving soil,

water, and other natural resources.

The cultural, social and

economic structures for modern East

Texas were shaped and molded by the

early 20th century logging industry.

Mill towns have become cities; logging

railroads have become multi-lane highways;

and family-owned mills have become multi-national

corporations, all in the last 100 years.

There are few, if any, facets of modern

East Texas that have not been directly

affected, or influenced, by the boom-bust

cycles of the early 20th century logging

industry.

Tracking Historic Sites in the Texas National Forests

|

|

It is rare now to find a good

body of pine standing along the

railroad, the best must be sought

ten and fifteen miles back . .

. The hope of the forests is that

the State or the United States

government will intervene, and

pass laws limiting the cut to

certain sizes, also employing

a forestry patrol to guard against

fires and waste.-William Goodrich

Jones, following a horseback survey

of the East Texas pine forests

in 1898.

|

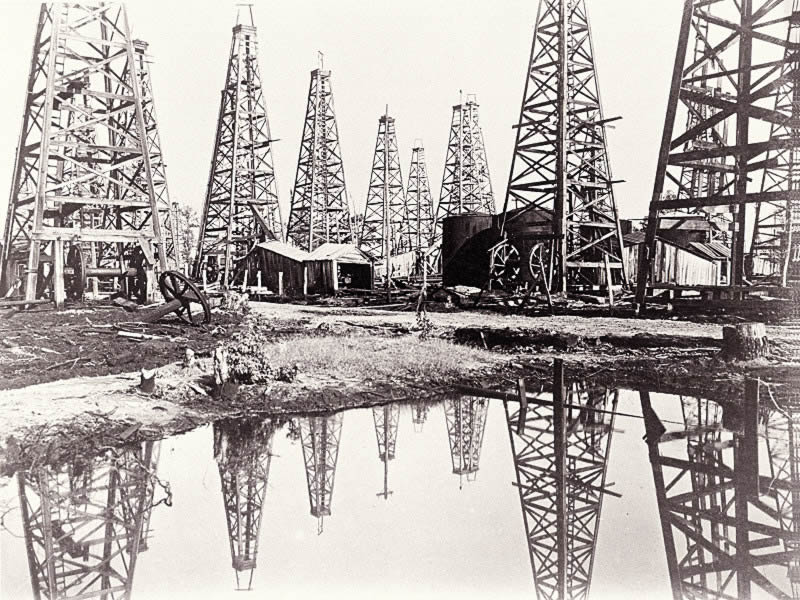

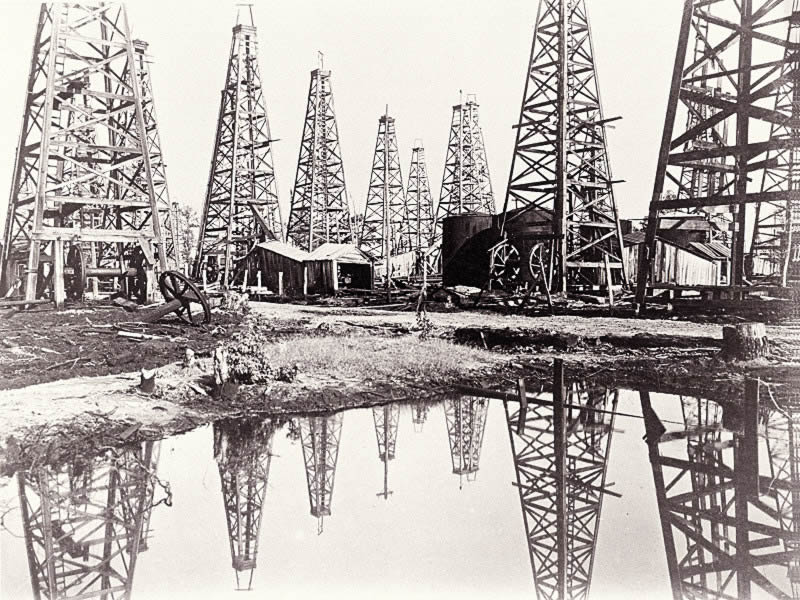

Wooden derricks are reflected in

an oil field pond at Sour Lake,

Texas. Lumber from East Texas provided

building materials for industries

across the state, from oil derricks

to rail ties. Photo courtesy of

Center for American History, University

of Texas at Austin. Click to enlarge. |

|

|

| |

East Texas Sawmill

and Rail Data Bases

|

|

Counties

|

# of Mills

|

# of Trams &

RRs

|

|

Angelina

|

178

|

34

|

|

Houston

|

151

|

9

|

|

Jasper

|

98

|

25

|

|

Montgomery

|

272

|

35

|

|

Nacogdoches

|

272

|

25

|

|

Sabine

|

98

|

9

|

|

San Augustine

|

217

|

16

|

|

San Jacinto

|

86

|

6

|

|

Shelby

|

273

|

10

|

|

Trinity

|

37

|

19

|

|

Walker

|

125

|

19

|

|

|

|

|

The remains of the early

20th-century logging industry which

can be found in the four National Forests

in Texas represent the full range of

logging industry-related sites and features.

Major mills and mill towns, such as

Aldridge and 4-C, represent the highest

level of development, with multiple

saws, large residential areas, commissaries,

hotels, schools, churches, and other

conveniences one would expect in a small

community. Smaller front camps, such

as Bannister, Brittain, Wilburn and

Ragtown, while smaller and only temporarily

occupied, contain equally complex features

as the larger mill towns. These essentially

mobile encampments were laid out in

a precise pattern with primary and intersecting

secondary thoroughfares lined by tents

or other types of temporary housing.

In 1993, the Texas Forestry Museum began

development of a database of historic sawmills in the

twelve county area defined as the Deep East Texas Council

of Governments. The Museum was joined in this development

by the T.L.L. Temple Archives, the Sam Houston Regional

Library, the USDA Forest Service and the School of Forestry

at Stephen F. Austin State University. By the end of

1994, over 5,500 sawmills and logging industry related

sites, located in forty counties from the Red River

to the Gulf Coast in the eastern third of Texas, were

listed on the database. By the end of 1995, a linked

database of Steam Logging Rail Roads had been also been

developed. In 1998, the sawmill database was made available

to the general public through the Texas Historic Sites

Atlas Project, Texas Historic Commission and Texas Archeological

Research Laboratory.

|

To learn more about historic logging

sites in the Texas Pineywoods, search

the online East Texas Sawmill Data Base©

and East Texas Tram and Railroad Data

Base© developed by the Texas Forestry

Museum and maintained by the Texas Historical

Commission. The sawmill data base documents

more than 4500 sites in 54 counties,

and the tram data base details more

than 300 trams and railroads that were

run as sawmill company lines. These

sites may be researched on the Texas

Historical Commission's Historic

Sites Atlas.

|

|

|