A woman cuts strips of mammoth (Ice-Age

elephant) meat on a hide, perhaps to be carried elsewhere

for dinner. In the background, the beast is being carved

up.

|

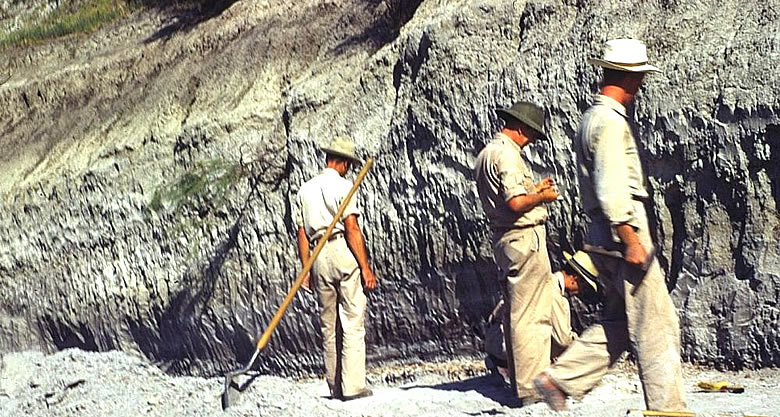

Folsom point found in place amid

bones of extinct bison, June,1951.

|

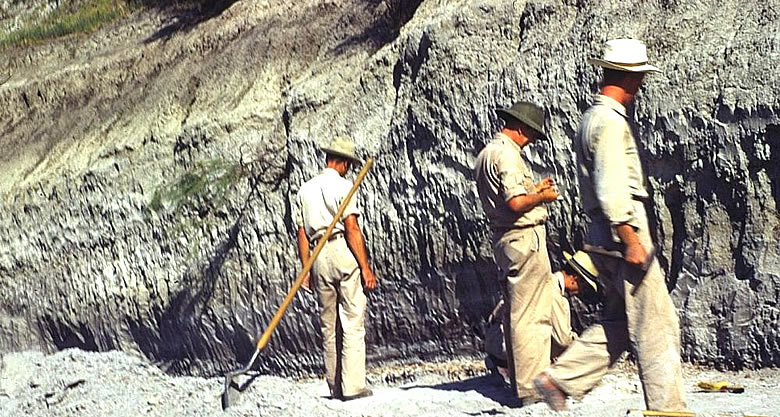

Geoarcheologist Vance Holliday points

out new evidence to TAS Field School Director Eileen

Johnson.

|

|

For over 13,000 years the inhabitants and visitors

to the Llano Estacado (Staked Plains) have frequented a locale

known today as the Lubbock Lake Landmark. Until recently the

main attraction was a major spring that flowed out of the

Ogallala aquifer and into Yellowhouse Draw. The abundant water

and sheltered draw was a haven for plants and animals. The

water, plants, and animals drew humans, beginning with Clovis

hunters and their families and continuing right on up into

historic times, each leaving behind a few traces. The end

result is an archeological record that has few parallels in

the southern High Plains—layer after layer reflecting

changing climates, environments, and cultures. Archeologists

and other scientists have been studying the Lubbock Lake site

for over 65 years and there is still much to be learned from

this remarkable locale.

The place takes its name from a reservoir created

in the 1930s in a U-shaped bend of Yellowhouse Draw, a tributary

of the Brazos River. Up until the late 1880s, a natural, spring-fed

lake existed in this same area. In the early 1900s, the springs

began to dry up, the victim of too many thirsty people and

their bountiful crops. In the late 1930s a project to dig

out (and hopefully renew) the springs turned up Folsom points

and other evidence of Paleoindian peoples. This led to the

first archeological digs in 1939 and 1941 under the sponsorship

of the Works Progress Administration (WPA). To run the excavation,

W. Curry Holden, Director of the West Texas Museum (now the

Museum of Texas Tech University) hired Joe Ben Wheat, a young

Texan who would later become a noted Paleoindian expert. But

everywhere the WPA crew dug, they soon hit water. While the

springs never came back, the water table had been raised temporarily

by the creation of the artificial reservoir. The Folsom deposits

lay deep below the water table and only a few Paleoindian

artifacts were recovered.

By the late 1940s, irrigation wells had drawn

down the water table considerably lower, making the Folsom-age

deposits accessible. Holden permitted new excavations to be

carried out under the direction of E.H. Sellards, Director

of the Texas Memorial Museum (TMM) at UT Austin. Sellards

and his TMM teams had been exploring a series of "Early

Man" sites including the famous Blackwater Draw in eastern

New Mexico. Geologist Glen Evans and paleontologist Grayson

Meade were in charge of the intermittent field work between

1948-1955 at Lubbock Lake. The main excavations were undertaken

in 1950-1951. Taking advantage of the lower water tables and

the almost vertical walls of the dredged-out waterway, Evans

and Meade were able to document a complex sequence of natural

and cultural deposits including bone beds associated with

Folsom artifacts. Glen Evans' color photographs can be seen

in the TMM 1950-1951

Photo Gallery.

Leg bone from extinct bison found in Bed 2,

notable for the finely banded layers of diatomite, pond

deposits of one-celled, algae-like organisms.

Since 1972, the Lubbock Lake Landmark has been

investigated by archeologist Dr. Eileen Johnson and geoarcheologist

Dr. Vance Holliday and their students and associates. Field

research has taken place almost every summer. The hallmark

of their work has been meticulous documentation borne out

of the realization that at Lubbock Lake most archeological

deposits are the result of one-time events. Here the smallest

trace can be a crucial clue to unraveling a "day-in-the-life"

occupational episode—a bison kill, an overnight camp,

a meal—sealed by the almost unbroken deposition of wind-borne

dust, overbank flood mud, or pond and marsh deposits.

Lubbock Lake is now a state and federal historic

landmark protected by a 336-acre preserve on the north side

of the city of Lubbock, Texas. The park contains the Lubbock

Lake Landmark (which includes a series of nearby archeological

locales along Yellowhouse Draw), an interpretive center, and

a research center operated by the Museum of Texas Tech University.

Today anyone can visit the interpretive center,

see the incredible outdoor display of life-size bronze statues

of Ice-Age animals, and sign up to participate in workshops

and tours. This is one of the most accessible archeological

and paleontological sites in Texas.. The interpretive center

has a very active public education program that involves thousands

of school children in the region every year. Check out the

Lubbock

Lake Landmark website for details.

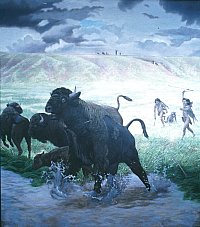

You can get a closer look now at some of the

vivid "day-in-the-life" recreations created by artists

from the Texas Parks and Wildlife Department for the Lubbock

Lake Landmark Interpretive Center in our special Mural

and Diorama Gallery.

Under the archeological leadership of Dr. Eileen

Johnson, the Texas

Archeological Society (TAS) held its 33rd annual

field school at Lubbock Lake Landmark June 3-11, 1993. Some

225 TAS members carried out site surveys and excavations at

various locales within the Landmark and at several ranches

elsewhere in the area. The biggest challenge was the relentless

wind and the dusty bone-dry conditions it brought. The campers'

tents "shook and flapped, and some collapsed" as

Dr. E. Mott Davis put it. In hindsight, it seems fitting that

those taking part in the field school had to face the exact

same forces of nature that shaped the Lubbock Lake Landmark

throughout its history. You can get a good look at many of

the activities in the TAS

1993 Photo Gallery.

|

Lubbock Lake Reservoir dredged out

and dried up, August, 1950. Unidentified man stands

above exposure where Folsom deposits were found.

Click images to enlarge

|

Folsom points from TMM excavations.

The specimen on the left and the one on the right are

casts of the originals.

|

Archaic hunters spring up from the

grass to hurl darts with atlatls at bison at the lake's

edge. The hunters disguised themselves as wolves and

slowly crept closer before springing. On the horizon

family members watch the scene hoping for a successful

hunt.

|

Jaq Jaquier takes note as TAS members

begin a new excavation at Lubbock Lake Landmark.

|

|