Sliver trade goods from 18th and

19th century Caddo sites. Courtesy Tim Perttula.

|

At historic Caddo sites, Caddo-made

pottery is often found mixed with trade wares from Europe.

Courtesy Tim Perttula.

|

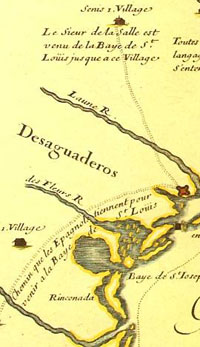

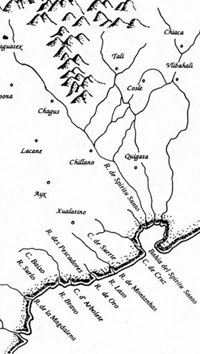

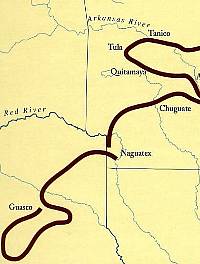

1650 French map by Nicolas Sanson

D'Abbeville entitled "Amérique Septentrionale."

Caddo groups including the Nacguatex are shown 400-500

miles east of their actual locations, reflecting the

poor knowledge of North American geography at that time.

Click to view larger image and a more detailed view.

|

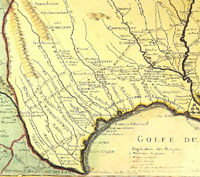

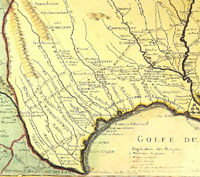

Attractive but very inaccurate 1705

French map by Nicolas de Fer entitled "Les Costes

aux Environs de la Riviere de Misisipi." Click

to view larger image and a more detailed view.

|

:

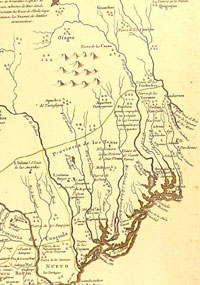

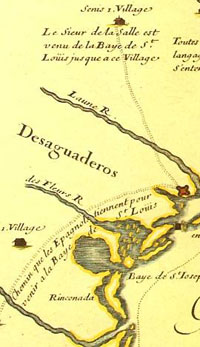

1718 map by Guillaume Delisle entitled

"Carte de la Louisiane et du cours du Mississipi."

This map benefited from the latest accounts of French

explorers and trading missions and fairly accurately

shows the physical and cultural geography of the Caddo

Homeland. Click to view larger image and a more detailed

view.

|

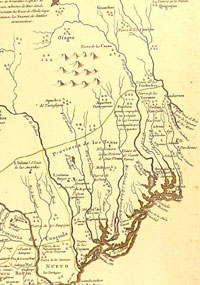

1768 Spanish map by Mexican-born

cleric and leading scientist José Antonio de

Alzate y Ramírez entitled "Nuevo Mapa Geografico

de la America Septentrional." This map shows relative

placements of Caddo groups fairly well, but the rivers

are not depicted accurately. French maps at the time

were greatly superior. Click to view larger image and

a more detailed view.

|

Redrawn version of the Terán

map of the Cadohadacho settlement (Upper Nasoni) on

the Red River in 1691. Note features identified in the

legend. From Sabo, 1992, courtesy Arkansas Archeological

Survey.

|

Osage warrior as depicted by the

French artist Julien Fevret de Saint-Memin in the early

1800s. Well-armed by the French, the Osage were bitter

enemies of the Cadohadacho groups.

|

Caddo-made earthenware bottles from

Allen phase, historic Caddo sites, about A.D. 1650-1750.

TARL archives.

|

Beginning in the 18th century, iron

axe and hatchet heads made in Europe for North American

trade were highly sought-after by the Caddo and other

Indian groups. These examples were found by looters

in historic Caddo graves in the vicinity of Titus County.

|

|

|

| Like

the ripples of skipped stones on a pond, spreading and

deflecting off of one another, the impacts of Old World

intruders reverberated all across North America. |

Keno Trailed, Glendora variant bottle

from the Cedar Grove site in southwest Arkansas, probably

made between 1700-1750. Courtesy Picture of Records.

|

Natchitoches Engraved, Lester Bend

variant, bowl from the Cedar Grove site in southwest

Arkansas, made about 1650. Courtesy Picture of Records.

|

Archeologists Kathleen Gilmore and

R. King Harris at the Roseborough Lake site.

|

Metal artifacts of dating to the

18th- and 19th-centuries found at the Roseborough Lake

site by King Harris. TARL archives.

|

Tiny Nacogdoches Engraved bottle

from Caddo burial at Rosenborough Lake excavated by

King Harris. TARL archives.

|

Caddo pottery from Roseborough Lake

found by King Harris. TARL archives.

|

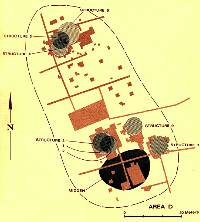

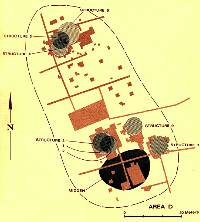

Schematic layout of the Allen phase

Caddo hamlet at the Deshazo site. Most of the houses

stood on either side of an open plaza. On the opposite

side of the creek was a single "special structure"

and a small cemetery. TARL archives.

|

|

In the last decade, Caddo archeologists and

ethnohistorians have studied anew the contact between Europeans

and Caddo peoples seeking to better understand how contact

changed Caddo societies. Part of this renewed ethnohistoric

and archeological interest has focused on reconstructing the

precise routes of Spanish and French explorers and colonists,

especially that of Hernando de Soto. At the same time, Caddo

researchers have been reconsidering the socio-political character

and ethnic identity of prehistoric and early historic Native

American groups.

In June, 1542, the De Soto entrada, led by Luis

de Moscoso, entered into the Caddo world and over the

next seven months passed through Caddo lands in present-day

Arkansas and Texas. Perhaps not far behind were the Old World

epidemic diseases. While Europeans would not tread again on

Caddo lands for 144 years, the Caddo world continued to feel

the impact of the spreading European colonization. Like the

ripples of skipped stones on a pond, spreading and deflecting

off of one another, the impacts of Old World intruders reverberated

all across North America.

Yet, despite close scrutiny of archeological,

bioarcheological, and historical data, no real consensus as

been reached on the precise effects of De Soto's first intrusion

on the Caddo world. The interwoven and still unsettled questions

include: How did Caddo populations change through time and

across the homeland? When did epidemic diseases enter the

Caddo area? When did post-contact population declines occur?

And, what were the cultural impacts of those declines on Caddo

societies and communities?

One thing is clear, the all-too-easily (and

often) told story: "when the evil Spanish (and somewhat

less evil French) came, the Caddo world was quickly ruined,"

is not true. The consequences of European colonization were

ultimately catastrophic for Caddo peoples, but these unfolded

in fits and starts over several centuries. Indeed, the story's

twists and complications do not fit within a simple plot.

When La Salle's expedition arrived among the

Hasinai groups in 1686, most Caddo peoples lived primarily

in relatively small groups on the Red River and in East Texas.

Over the next century and a half Europeans laid claim to their

lands and loyalties, and the Caddo found themselves wedged

between the outer edges of the French and Spanish empires.

Epidemic upon epidemic ravaged Caddo populations—possibly

by as much as 95 percentage between 1691 and 1816. Yet, European impact

was not all disastrous. The Caddo were situated perfectly to

participate in the French fur trade, and they traded guns,

horses, and other essential items to Indian groups and Europeans.

In the process they developed new trade and economic networks,

and acquired new European goods and ornaments. The resulting

economic symbiosis between the Caddo groups and Europeans

was the key to the political success, resilience, and strength

of the Caddo tribes through much of the colonial era.

Caddo Territory

Over a century passed after De Soto's failed

entrada before the Spanish again took notice of the Caddo,

This time the Spanish came from the opposite direction, the

southwest. In the mid-1600s, Spanish priests learned about

the Caddo at La Junta de los Ríos (the confluence of

the Rio Grande and Rio Conchos), some 550 miles west of the

nearest Caddo village. Jumano Indians, famed as long-distance

travelers and traders, told the Spanish about the "Great

Kingdom of the Tejas," a populous and well-governed

people. The term "Tejas" referred mainly to the

Hasinai groups of east Texas, but the characterization applied

equally well to the greater Caddo world.

Before the initial European contact, in the

early 1500s, the Hasinai Caddo groups lived in permanent communities

throughout the upper Neches and Angelina river basins. They

are represented archeologically by sites belonging to the

Frankston phase (ca. 1400-1600) and Allen (ca. 1600-1800)

phases of what archeologists call the Anderson Cluster. Although

occasional Hasinai Caddo groups or bands lived west of the

Neches and Trinity rivers in historic times, they usually

did not go beyond that boundary, "unless going to war,"

according to Henrí Joutel, the chronicler of the La

Salle expedition. The Hasinai groups continued to live in

the upper Neches and Angelina river basins until they were

driven out of East Texas by the leaders of the Republic of

Texas after 1836.

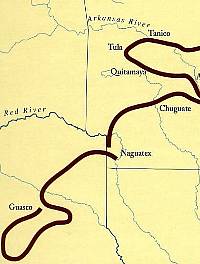

European maps of the late 1500s to the mid-1600s

located Caddo and Caddo-allied groups such as the Naguatex,

Nisoone (Nasoni), Lacane, Ays, Xualatino (or Soacatino) and

Guasco on a western tributary of a drainage labeled Rio de

Leon or Rio de Spiritu (Espiritu) Santo, the Mississippi River,

but it is clear from similarities between 1572 and 1656 maps

that geographic knowledge of the territory of the interior-living

Caddo and other Texas tribes had not changed over that period.

It was not until Europeans (principally La Salle's group)

ventured again into the Caddo area in the 1680s, that the

territory of the various Caddo tribes, their non-Caddo allies,

and their enemies became better understood.

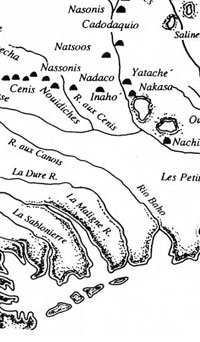

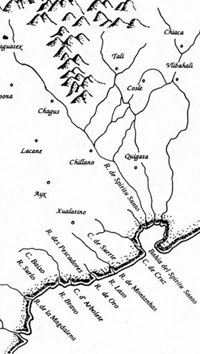

Delisle's map of 1703 places a series of related Caddo groups

along a considerable stretch of a western tributary of the

Mississippi River, obviously the Red River. Beginning on the

lower Red River with the Nachitoches [Natchitoches] and proceeding

up river, other Caddo groups included the Nakasa (one of the

enemies of the Kadohadacho in 1687, according to Joutel),

Yatache [Yatasi], Natsoos [Nanatsoho], Cadodaquiro [Cadohadacho],

the [upper] Nachitoches, and the Nassonis [upper Nasoni].

Upstream from them on the Red River were the Canouaouana and

Chaquanhe tribes, apparently enemies of the Cadohadacho, again

according to Joutel.

The westernmost Caddo groups were shown by Delisle

(1703) living on and near the Rio aux Cenis (probably the

Neches River), Cenis (or Senys) being the French name for

the Hasinai Caddo. Other than the mistake of having the Rio

aux Cenis running into the Red River, Delisle's map shows

that the French had a good understanding of the locations

of the various Hasinai Caddo groups, from the Inahe [Hainai]

to the east (on the Angelina river), the Nadaco and Nassonis

[lower Nasoni] to the north and west, and a series of Cenis

(Hasinai) communities along the western boundaries of their

territory. No Caddo communities are depicted west of the Trinity

River (Rio Baho), with the closest non-Caddo communities living

between the Trinity and Brazos (La Maligne R.) rivers. On

the Brazos River lived the Canohatino tribe, one of the enemies

of the Hasinai Caddo. That tribe felt the brunt of a French-Caddo

attack in 1687 where more than 40 Canohatino were massacred

by the joint armed forces.

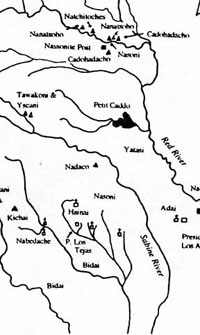

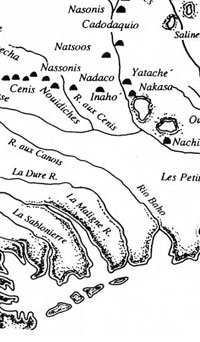

By the 1750s, the Europeans (especially the

French) possessed a much better perception of the location

of the Hasinai Caddo groups and related Caddo tribes in east

Texas and western Louisiana. This is not surprising considering

that, reportedly, there was a French trader living at each

of the major Caddo settlements, even those in the province

of Texas (which was claimed by Spain). In a 1757 French map,

Caddo groups are dispersed from east of the Sabine River (Rio

Zavinas), near the Spanish presidio at Los Adaes, to just

west of the Neches River (Rio de Nechas), with Spanish missions

in their midst at Nacoudoches [Mission Nuestra Senora de los

Nacogdoches] and de los Hays [Mission Nuestra Senora Dolores

de Ais].

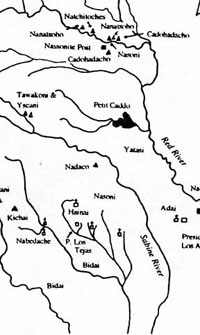

Between the 1750s and the 1780s, the Tawakoni,

Yscani, and Kichai tribes, affiliated Wichita-speaking tribes,

had moved south (from Kansas and Oklahoma) and settled in

large villages along the margins of the Post Oak Savanna,

in traditional Caddo hunting territory. The Hasinai Caddo

tribes and the Wichita groups became strong allies, and the

Caddo leaders were of great assistance in concluding formal

and peaceful relations between the Wichita-speaking tribes

and the Spanish in 1771-1772, and again between the Caddo,

the Wichita-speaking tribes, and the Republic of Texas in

1843. The Bidai tribe, also allies to the Hasinai, lived to

their south along the Trinity and Neches-Angelina rivers.

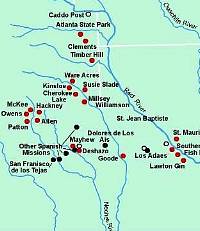

Because of the outbreak of epidemics at the

Spanish settlement of Nacogdoches in the late 1770s to early

1780s, the Nadaco Caddo moved north along the Caddo Trace

(a major trade path/road probably in existence for hundreds

of years) to resettle on the Sabine River, where they remained

until the establishment of the Republic of Texas. The Cadohadacho

groups, with populations also diminished by epidemics, by

this time had coalesced into one village for protection against

the Osage, and relocated by 1795 along a small tributary feeding

into Caddo Lake, a natural lake formed by the Great Raft along

the Red River valley. Most of the Cadohadacho remained in

the Caddo Lake area until 1842, while others had moved into

Indian Territory (Oklahoma) shortly after 1836, or had settled

in the upper Trinity River drainage.

The Hasinai Caddo groups—the Nacogdoche,

the Hasinai, and Nabedache—remained in their east Texas

homelands, living in the early 1800s outside of the Spanish

settlement of Nacogdoches, west to the Neches River, and north

of the El Camino Real. Anglo settlement had pushed immigrant

Indians from the Southeastern U.S., including the Biloxi,

Alabama, Coushatta, Choctaw, and Cherokee, into the Caddo

Homeland. These groups began to settle within traditional

Caddo territory, both north and south of Nacogdoches, as well

as along the Red River north and east of Caddo Lake. The Alabama

and Coushatta people asked for, and received, the permission

of the Cadohadacho caddi to resettle along the Red

River, and they became strong allies of the Caddo peoples.

This was not the case with the Choctaw, as conflicts began

between them and the Hasinai Caddo groups over hunting territories

almost immediately after the Choctaw moved into East Texas.

Later, however, the Choctaw allied with the Caddo peoples

and the Cherokee in war parties against the Osage.

Between about 1836 and 1842, the Hasinai, Nadaco,

and Cadohadacho tribes had all been forcibly pushed out of

East Texas, some moving into Indian Territory, while others

moved west into the upper Brazos River drainage. This was

the final and bitter end to the Caddo settlement of their

traditional homelands. Though the Caddo groups made a successful

agricultural living for a few short years in the hard but

seemingly fertile lands of the Brazos River valley, they were

never secure from Anglo-American encroachments, even when

settled on the Brazos Reserve in 1855. They were compelled

in 1859, according to John R. Swanton, noted ethnologist at

the Smithsonian Institution, "to abandon their homes,

the fruit of their labors, and the graves of their kindred,"

and were removed to the Washita River valley in Indian Territory.

Learn more about later Caddo history in Caddo

Voices.

Interaction with Friends and Strangers

No Caddo community, town, or mound center was

ever fortified, and there is little evidence in the archeological

record for warfare or violent conflict between the Caddos

and other peoples. That is, evidence of individuals dying

from wounds inflicted from an arrowhead, scalping, or forms

of mutilation after death are rare indeed, and seemingly very

rare when compared to contemporaneous Indian groups in the

Southern Plains and Southeast U.S. [Admittedly, the prevailing

poor preservation of bone in the typically acidic soils of

the Caddo Homeland lessens the chance that such evidence would

be spotted.] The Caddo circumstance is also quite a contrast

with the densely packed societies living in the Mississippi

Valley and interior Southeast, where heavily populated towns

were palisaded and where political and economic dominance

was asserted through warfare. Prehistoric and historic Caddo

settlement patterns are characteristically dispersed and lack

any hint of a defensive posture.

This is not to say that Caddo peoples can be

regarded as peaceful and non-aggressive. Indeed, French and

Spanish documents of the 17th and 18th centuries clearly show

that the Hasinai and the Cadohadacho had many enemies, some

of long-standing like the Chickasaw, Lipan Apache, and Osage.

Relations with many of their other enemies probably alternated

over the years between alliances and hostility, depending

upon the needs of the moment, particularly the willingness

to trade and confront common enemies. All this was to change

with the appearance and adoption of the horse and gun among

the Caddo and their Southern Plains neighbors.

By the 1680s, non-agricultural groups (such

as the various Apache bands) to the west and southwest of

the Hasinai Caddo tribes had horses in numbers, but lacked

guns, which the Caddo peoples began to obtain (if sometimes

only periodically) in trade with the French fur traders. The

Hasinai Caddo peoples also had horses obtained through trading

with their allies on the prairies and plains of east-central

and southern Texas (where herds of wild mustangs now roamed)

and through raiding on their enemies. The Caddo groups were

well placed at the juncture of the Horse Frontier and

the Gun Frontier. As of about 1716, the Hasinai and

the Cadohadacho territories marked, respectively, the frontier

of horses moving eastward, and of muskets moving westward

in trade.

Access to desirable goods such as guns and horses

contributed strongly to the maintenance and expansion of Caddo

social and political power relationships with their Native

American neighbors, allies, and enemies. Horses and guns allowed

the Caddos to increase their bison hunting in the prairies

and plains well west and southwest of their territory. This

probably exacerbated existing animosities with peoples to

the west, but did not prevent Caddos from establishing new

hunting territories and new settlements astride Indian and

European trade routes. It also assured the Caddo peoples of

continued trade with the Europeans and an active role in arranging

political and economic measures between other Native Americans

and the Europeans that directly affected their well-being.

Fighting between the Caddo and their enemies

mainly consisted of hit-and-run raids upon an enemy, aimed

at capturing or killing a few foe and snatching booty, rather

than battles with large numbers of casualties on either side.

This enmity did not prevent the Caddo peoples from hunting

and trading regularly west of the Trinity River both before

and after they had the horse. The Hasinai Caddo peoples were

quite familiar with these regions, giving Fray Mazanet in

1691 their names for each of the streams from the Nabedache

village on San Pedro Creek (just west of the Neches River)

200 miles to the southwest in the San Antonio area. Once they

acquired horses, Caddo hunters expanded their forays into

portions of north, central, and south Texas to obtain deer

and bison hides for trade with the French.

For the Cadohadacho tribes, on the other hand,

according to Joutel in 1687, "most of the hostile tribes

are to the east...and have no horses; it is only those towards

the west which have any." The hostile tribes to the east

(especially the Osage) had plentiful supplies of guns obtained

from both French and British sources, and they aggressively

raided Caddo villages and seized Caddo slaves, horses, and

furs.

This disparity in supplies of the coveted horses

and guns led to a profitable trade for the Caddo peoples,

either in direct exchange or acting as middlemen. But over

the long-run, the trade bounty did not serve to better protect

them against the Osage and Chickasaw, who ceaselessly raided

the Caddo for slaves from the late 1600s to the early 1700s.

Shortly thereafter, the Caddo became involved in the thriving

traffic in Apache slaves, an outcome of the Southern Plains

warfare between the Comanche and Apache that began in the

early 1700s. The Caddo traded Apache children for European

goods at the French and Spanish markets at Natchitoches and

Los Adaes. By the 1760s, the Osage were expanding their hunting

and trapping territory to obtain more furs, however, and their

depredations against the Caddo changed to a war of conquest.

Over a period of about 80 years, the Osage succeeded in reducing

the Kadohadacho tribes from five villages to only one. This

reduction forced the Cadohadacho, along with the Yatasi, to

move far down the Red River, closer to the European post and

fort at Natchitoches, abandoning the Great Bend area, in a

desperate attempt to escape the aggressive expansion of the

Osage tribe.

Caddo Responses

European epidemic diseases among the Caddo peoples

resulted in regional population declines (certainly noticeable

after 1691), group movements, and the eventual coming together

of once-separate Caddo bands. It has been estimated that Caddo

populations plummeted by as much as 75 percentage between 1687 and 1790

due to epidemics. Population declines and settlement changes

appear to have been more substantial along the major rivers,

as seen by the complete abandonment of the Ouachita and Little

rivers by 1700, and the Arkansas River earlier in the 1600s,

but there was no major abandonment of east Texas by the Hasinai

Caddo in historic times. The view here is that the strong

Kadohadacho, Hasinai, and Natchitoches alliances ("confederacies")

that were formed in the early 1700s were a direct result of

regional population decline, village abandonment, and group

coalescence.

While the establishment of the Spanish missions

in the southern part of the Caddo homeland failed to convert

Caddo peoples into Christianity and to resettle Caddo communities

around the missions, some Caddo apparently chose mission life

rather than remain in east Texas. After the east Texas missions

failed in the early 1730s, a few Tejas (Hasinai) individuals

were enrolled at missions San Jose and Valero [also known

as the Alamo] in San Antonio in the mid to late 1700s. The

vast majority, however, stayed put in the homeland.

The Caddos' participation in the fur trade (mainly

deer and buffalo hides) had important consequences for them,

as well as for their European partners in the trading system.

Through the fur trade, the Caddo acquired and accumulated

large quantities of desirable European goods, which they in

turn kept for their own use or exchanged with other Indian

groups for furs and horses, all the while exploiting existing

trade networks to their advantage. Trade success also allowed

the Caddo to expand their hunting activities into new territories,

and/or reoccupy abandoned river valleys (such as the upper

Sabine River basin after about 1740) for the same purposes.

The Caddo's participation in the European frontier economy

was recognized and rewarded by the French and Spanish governments

through programs of annual gifts and presents. Such programs

reflect the existence of political and economic commitments

between the Caddo peoples and the Europeans. These all had

considerable economic, military, and social prestige to the

Caddo peoples in their dealings with other Indian groups.

George Sabo's ethnohistorical studies of late

17th and early 18th century Caddo societies in East Texas

have shown how the Caddo drew Europeans into their world by

including them in sacred and secular rituals and ceremonies.

This inclusion gave the Caddo the means to absorb and manipulate

Europeans. In effect, the Caddo made foreigners in their midst

part of the tribe and created intricate social relationships

with them following the same basic principles that ordered

and shaped Caddo societies. This helps explain why Caddo rituals

and greetings seemed excessive to Europeans and why discussions

of these exchanges seem to dominate much of the Spanish and

French archival documents. Similar interactions are sadly

missing from the observations and records of the Americans,

strongly hinting that the Caddo by the 1810s were unable to

exploit existing American trade and military relationships

in the same way they had the Spanish and the French.

Even in the late 18th and early 19th century,

Caddo political leaders were still recognized as politically

astute and masterful mediators and alliance-builders between

European and Anglo-American explorers and colonists, as well

as with Native American groups such as the Comanche, Wichita,

and Apache tribes. Among the most influential Caddo leaders

were the caddices (or caddis) Tinhiouen (from ca. 1760-1789)

and Dehahuit (from ca. 1800-1833) of the Kadohadacho, and

Iesh or Jose Maria (from about 1842 to 1862) of the Anadarko

or Nadaco tribe.

As their world was transformed from the outside,

Caddo ritual beliefs and political practices changed on the

inside as well. For instance, Father Gaspar Jose de Solís

noted in 1768 among the Nabedache, the westernmost of the

Hasinai Caddo tribes, that a Caddo women called Santa Adiva

was the principal authority, instead of the xinesi

and caddi, hereditary male leaders. Such a change was

likely related to epidemics that had decimated Hasinai villages

after the coming of the missionaries, as well as to the Spanish

policy of presenting the staff of leadership to an elected

leader, rather than following the then unbroken hereditary

chain.

In the larger context of Caddo society, however,

the hereditary chain of Caddo leadership—strong, peace-

and alliance-building caddis—seems to have continued

unbroken among the Hasinai and Kadohadacho; this ultimately

was the source of their strength. From European and American

accounts, it is clear that the Caddo political leaders played

important and influential roles in shaping the major political

decisions of the day to favor the Caddo peoples, decisions

that affected other Native American groups and Europeans,

and in arranging and bringing to fruition alliances (even

though temporary) between the Caddo, powerful Native American

groups like the Comanche and Wichita tribes, and European

nations.

Waves of Anglo-American immigrants after about

1815 established permanent, ever-expanding settlements in

the region. It was the Caddos' misfortune to have been living

on choice and fertile farmlands desired by the Anglo-Americans.

In a few short years, they were dispossessed of their traditional

homelands by the U.S. and Texas governments, their lands and

goods swindled from them by U.S. Federal Indian agents in

the Caddo Treaty of 1835, and eventually they were forced

in 1859 to relocate from the Brazos Reserve in Texas to the

Wichita Agency in western Oklahoma (then Indian Territory).

Shortly thereafter, they were caught up in the Union and Confederate

struggle for the Indian Territory during the Civil War, and

with little trust for either the rebel or federal governments,

the Caddo tribe abandoned their lands in Indian Territory

for lands in Kansas.

Historic Caddo Archeology

Finding, recognizing, and positively identifying

Caddo archeological sites dating after A.D. 1680, even famous

ones mentioned repeatedly in historical documents, has often

proven hard to do. Most of the archeological research done

on "historic-era" Caddo sites has involved sites

and site components dating to the protohistoric era, that

part of the Late Caddo period from 1542 to about 1680. Items

of European manufacture are extremely rare in sites dating

to this period, as could be expected because the Caddo did

not have sustained contact with Europeans until after 1686.

But it is surprising that early 18th-century Caddo sites may

have little or no definitive evidence of European contact.

For instance, a well-studied Late Caddo farmstead

called the Cedar Grove site in Lafayette County, Arkansas,

is thought to date to A.D. 1650-1750 because of close matches

between its Caddo pottery and that found elsewhere of known

age (a technique known as "cross-dating"). Yet,

apart from two bone "beads" found in a grave, there

is not a single item from among the thousands of artifacts

recovered at the site that could be of European manufacture.

(A recent study suggested the bone "beads" were

more likely to be children's toys by by the Caddo.) Still,

the ceramic evidence strongly suggested the site dated to

early historic times. To confirm their strong suspicions,

the archeologists who analyzed the Cedar Grove site tried

radiocarbon dating, archeomagnetic dating, and thermoluminescent

dating. All three yielded frustratingly imprecise or inaccurate

age estimates. Still, cross-dating the site's large ceramic

collection shows pretty convincingly that the site spans the

late 17th and early 18th centuries.

Other historic Caddo sites have been located

by matching up places mentioned in historic documents with

archeological sites. But this too can be an exercise in frustration.

Early maps and travel logs were imprecise, even in distinctive

river valleys such as that of the Red River. The Red River

has meandered throughout its history, carving new channels

and abandoning old ones when major floods strike. Today the

river continues to change its course from time to time despite

the best efforts of the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers. Early

maps can help identify where and when the river has changed,

but topographically accurate maps were not made in the region

prior to the late 19th century. And it is not just the river's

swinging course. Historic and modern land use practices, especially

farming, but also the construction of roads, bridges, and

levees, have severely altered the lay of the land.

A good example of the challenge of precisely

locating and identifying known sites important to Caddo history

is case of the Roseborough Lake site in Bowie County,

Texas. This site overlooks an oxbow lake (abandoned channel)

in the Red River Valley about four miles upstream from the

Hatchel-Mitchell-Moores site complex (the upper Nasoni village

visited and depicted in the Terán map). The Roseborough Lake

locality has long been known to contain abundant European

artifacts dating to the early to mid-18th century (and later).

Among them are items of earthenware, porcelain, and stoneware,

as well as many kinds of metal artifacts (gun parts, knives,

nails, etc.), glass beads, and glass bottle fragments. Historic

documents indicated that Benard de La Harpe established a

French trading/military post in the vicinity in 1719. Were

La Harpe's post and the Roseborough Lake locality one and

the same, as a study published in 1973 tentatively concluded?

Or was Roseborough Lake instead the scene of the later Caddo

Post established and run by Alexis Grappe and his family in

the 1730s.

Historians and archeologists poured over old

accounts, maps, and the many European artifacts from the site

and debated these possibilities. There were other candidate

localities, including the Moore's part of the upper Nasoni

village. The matter was not decided conclusively until historical

archeologist Kathleen Gilmore from North Texas State University

brought her undergraduate students to Roseborough Lake in

1976 and carried out test excavations. Gilmore carefully compared

what she found at the site (and that found by others) with

statements in the many related documents, some of which were

contradictory or at least ambiguous. Roseborough Lake, she

concluded, must be the later Caddo Post of Alexis Grappe and

not that of La Harpe. The timing of Gilmore's fieldwork was

fortuitous. Only a few years later the property was sold to

an international soybean company headquartered, ironically,

in France. The company soon cleared the entire area and contoured

it for commercial farming, rendering the Roseborough Lake

site virtually unrecognizable.

|

Glass trade beads from 18th- and

19th-century Caddo sites. Courtesy Tim Perttula.

|

The route of the De Soto entrada

in 1542 through the Caddo Homeland as reconstructed

by Charles Hudson. From Sabo, 1992, courtesy Arkansas

Archeological Survey.

|

Redrawn version of 1656 map by Nicolas

Sanson entitled "Le Nouvea Mexique et la Floride."

Note Caddo groups Naguatex, Nisoona, Lacane, Ayx, and

Xualatino on a western tributary of R. de Spiritu Santo.

From Perttula, 2001, courtesy Texas Archeological Society.

|

Redrawn version of 1703 map by Guillaume

Delisle entitled "Carte de Canada et du Mississippi."

Note Caddo groups on a western tributary (the Red River)

of the Mississippi River, including the Nachitoches,

Ouachita, Nakasa, Yatache, Natsoos, Cadodaquiro, Nassonis,

and Nachitoches [upper], and another series of western

Caddo groups (Inahe, Nadaco, Nassonis, Nouidiches, Cenis,

Ayeche, Nacanne, and Xayecha) around R. aux Cenis. From

Perttula, 2001, courtesy Texas Archeological Society.

|

Redrawn version of 1757 map entitled

"La Province de Texas and Nueva Luciana."

Note the western Caddo and Caddo-allied groups (Adais,

Haysitos, Nacoudoches, Nechas, Nazones, and Texas) between

the Presidio de los Adaes and the Rio de Nechas. From

Perttula, 2001, courtesy Texas Archeological Society.

|

Late 18th-century Locations of the

caddo or Kadohadacho and Hasinai Tribes on the Red River

and in East Texas, the Wichita Tribes (Taovayas, Tawakoni,

Yscani, and Kichai), the Bidai, and a band of Red River

Comanche. From Carter, 1995.

|

Redrawn version of 1801 map by Father

Puelles of the Provincia de Texas and Luisiana, showing

Hasinai tribes between the Sabine and Trinity rivers,

and the Kadohadacho or Caddo tribe west of the Red River

and near Caddo Lake. From Perttula, 2001, courtesy Texas

Archeological Society.

|

"Tuch-ee, Texas Cherokee"

by George Catlin. The Cherokee were one of many immigrant

Indian tribes from the Southeast that were pushed into

Texas by Anglo settlement.

|

Patton Engraved pottery from the

historic Caddo Allen phase, about A.D. 1600-1800. TARL

archives.

|

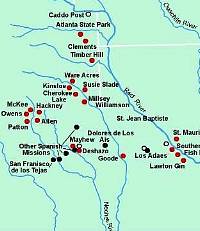

Location of some of the important

and better known Caddo and European sites dating to

the Early Historic period. Graphic by Dee Ann Story.

|

Keno Trailed, Phillips variant bowl

from the Cedar Grove site in southwest Arkansas, probably

made between 1700-1750. Courtesy Picture of Records.

|

Roseborough Lake, an oxbow lake (abandoned

channel) in the Red River Valley about four miles upstream

from the Hatchel-Mitchell-Moores site complex (the upper

Nasoni village visited and depicted in the Terán

map). Bowie County, Texas. TARL archives.

|

Students from North Texas State University

excavating at the Roseborough Lake site. The bricks

you see date from later occupations at the site. TARL

archives.

|

European pottery fragments dating

to the 18th- and 19th-centuries found at the Roseborough

Lake site by King Harris. TARL archives.

|

Map of the excavation units and structures

in one area of the Deshazo site. TARL Archives.

|

Two of the intersecting house patterns

at the Deshazo site, showing that some of the houses

were rebuilt in almost the same spots. Caddo houses

probably lasted 10-15 years before the wood posts rotted

and had to be replaced. TARL archives.

|

Those who excavate Caddo sites in

the middle of summer like to start soon after dawn.

Deshazo excavations in progress. TARL archives.

|

|