Polished stone celts such as these

were included as grave offerings in Mound C and were

also found within postholes. They were used as axes,

but some of those found as offerings are so small they

do not look like functional objects. Davis site. TARL

archives.

|

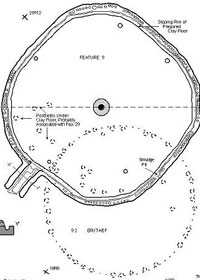

The "Ceremonial Maze"(Building

F35) as outlined by WPA excavators. View looking west

across the "wings" thought possibly to represent

those of a turkey, a special bird to the Caddo. The

orientation of the narrow extended entranceway (or "neck")

on the right (north) appears to have shifted a few degrees

during remodeling, making it look as if the entrance

was blocked. The raised ridge of baked clay on the opposite

"tail" end is the result of the intentional

burning of the structure when it was dismantled hundreds

of years ago. TARL archives.

|

Building F9 during the WPA excavation.

Over 4,600 pottery sherds, a piece of copper attached

to a cord, fragments of three clay pipes, a ceramic

ear spool, a ceramic effigy, and various stone tools

and flint flakes littered this unique semi-rounded building

at the Davis site. Some of the artifacts are visible

in this photo. TARL archives.

|

Building 125 during excavation. Thought

to be a fire temple, the intensively burned deep central

hearth had yet to be excavated when this 1970 photo

was taken, yet its location is obvious. The two large

holes nearby are where two of four large posts stood

around the hearth (the postholes have been cleared by

the excavators). TARL archives.

|

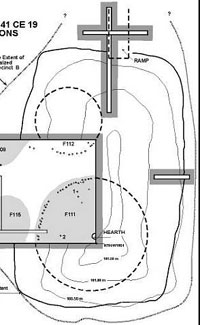

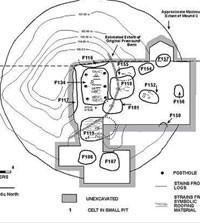

Plan map of Building 125 and cross-section

of its deep, multi-layered central hearth. Graphic by

Dee Ann Story.

|

The excavation walls in the central

area of Mound C revealed a complicated sequence of cut

and fill layers. The intentional use of contrasting

soil colors by the ancient Caddo probably had symbolic

meaning. It also allowed the archeologists to unravel

the sequence of events. TARL archives.

|

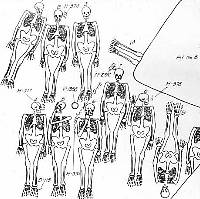

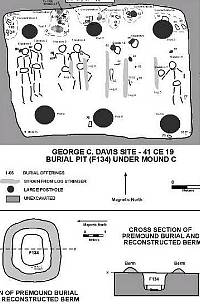

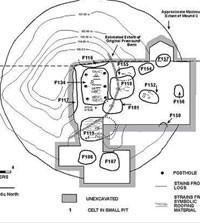

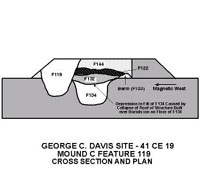

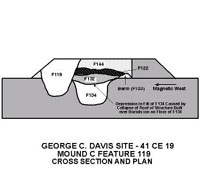

Plan map of the "log tomb" (Feature 134) so

named because of the two rows of massive log posts that

ran down the walls of the tomb and presumably supported

a low roof only about three feet above the tomb flour.

The construction of the log tomb is inferred from stains

and traces as no wood survived. On the floor of the log

tomb were eight individuals in extended positions (heads

to the north) and neatly arranged into four pairs. Graphic

by Dee Ann Story.

|

Front and back of a set of incised

stone earspools. Mound C, Davis site. TARL archives.

|

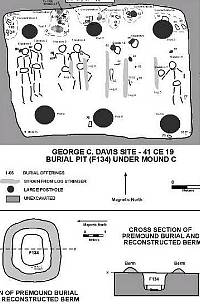

This small tomb is typical of many

of those under the outer part of Mound C. It measured

about 7 by 5.5 feet and contained a single engraved

pottery bottle as a grave offering. No bones were preserved,

probably because the burial pit was relatively shallow

(8 feet deep) and on the edge of the mound. Graphic

by Dee Ann Story.

|

|

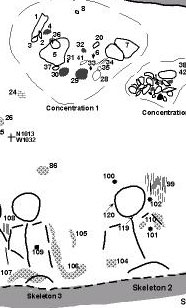

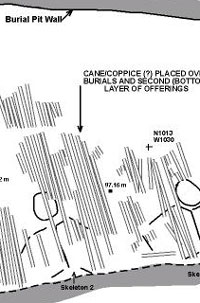

Floor of the cane tomb. (Click to enlarge.) As can

be seen, the four individuals were arranged in extended

positions in two pairs. The pair on the right was

obviously paramount (most important) as they were

widely spaced with arms outspread (the legs were not

exposed by excavation), heads placed facing up, and

accompanied by high-status grave offerings. In contrast, the other pair of individuals was closely

spaced, with arms to the sides, had few grave offerings,

and had been arranged so that the heads faced east,

toward the paramount pair. The lesser pair (perhaps

slaves) were probably sacrificed in honor of the paramount

individuals (of whom the one on the far right was

accompanied by the greatest amount of offerings and

personal ornaments.) Graphic by Dee Ann Story. |

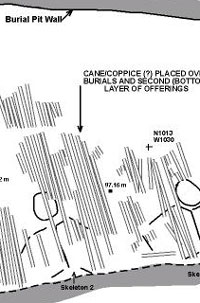

Drawing showing the layer (or coppice)

of river cane that may represent the symbolic roof of

the tomb. Graphic by Dee Ann Story.

|

This cluster of grave offerings on

the north side of the log tomb included a celt, a marine

shell "dipper," and an upside-down ceramic

bowl. TARL archives.

|

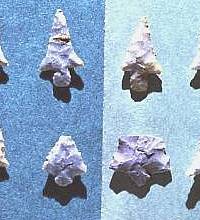

Gahagan bifaces—extremely thin

knives made of high quality flint—left as offerings

in the cane tomb. TARL archives.

|

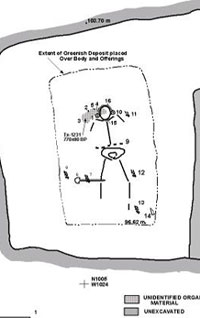

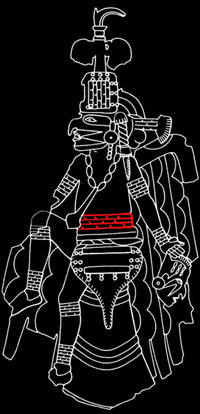

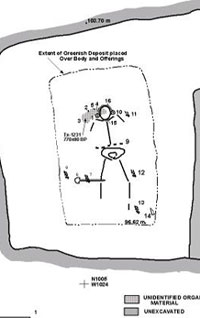

This large tomb in Mound C contained

a single young adult resting on his or her (sex not

determined) back with arms and feet spread out. Around

the waist was heavy belt made of tubular marine-shell

beads (item 9). At the right knee was a greenstone scepter.

On either side of the head were copper-covered stone

earspools apparently held in place by a pearl-beaded

band that went over the top of the head. Frank Schambach

thinks this individual is dressed and positioned as

the Bird-Man, a suggestion we find compelling. Graphic

by Dee Ann Story.

|

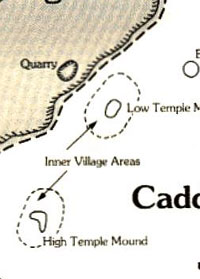

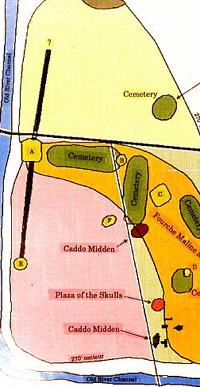

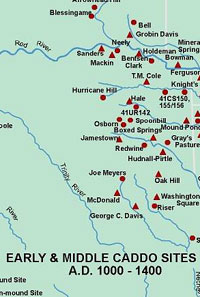

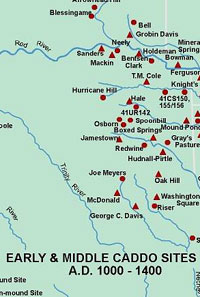

Shown here are some of the better-known

and important Early and Middle Caddo sites dating to

roughly A.D. 1000-1400. Map by Dee Ann Story.

|

|

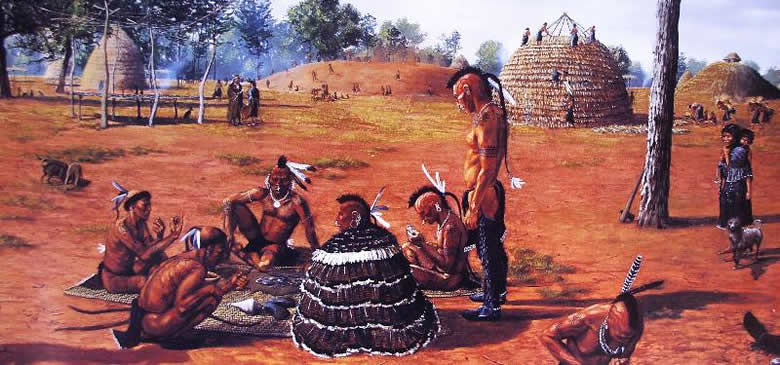

Special Buildings and their Earthen Mounds

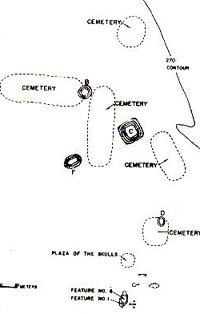

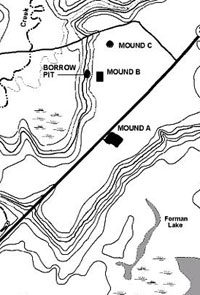

The three earthen mounds at the Davis site are

visible reminders of the Caddo community and of the generations

of villagers for whom the site must have been the sacred center

of their world. The mounds, which were built at different

times during the site's history, served various functions,

all of them important to the life of the community. Mounds

A and B were begun as low "capping" mounds that

purposefully covered (capped) the floors of dismantled temples

and communal buildings (collectively, "special buildings").

Then the top of Mound A (and possibly that of Mound B) served

as a platform upon which new special buildings were built.

Platform or temple mounds are one of the hallmarks of Mississippian

life. Burial mounds like Mound C had been around since early

Woodland days if not before.

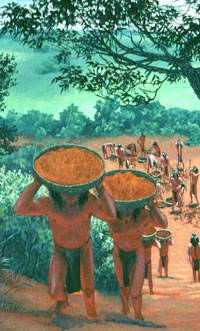

Each earthen mound at Davis was built in stages,

probably during short periods of time when the community pitched

in for the common good. The villagers dug up the soil from

areas below the low bluff that borders the wide, flat terrace

upon which the site sits. A large depression left by one of

the barrow pits where soil was removed can still be seen today

after 800 years of gradual infilling. Basketload after basketload

of soil was carried up the bluff, brought to the mound site,

and dumped. This was not a casual process, but a very deliberate

one done with care. Often the villagers selected layers of

soil having differing colors or textures for particular mound

construction layers, particularly in Mound C, the burial mound.

There, it is clear that certain colors must have be chosen

for their symbolic value. For example, a special green clay

obtained elsewhere in the Neches Valley was used to cover

certain of the shaft-like tombs that held the bodies of very

special members of the community. While we cannnot decipher

the specific meanings of the soil colors chosen a thousand

years ago, the patterning is clearly purposeful and must have

had deep symbolic value.

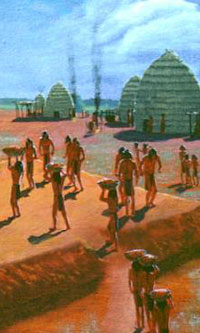

Mounds A and B mark the inner

precincts within the Davis community, a pattern than began

before the mounds were begun and one that continued for generations.

Within these precincts stood tall and often spacious beehive-shaped

wooden buildings with grass-thatched roofs that were larger

than ordinary houses. Some were probably the houses of community

leaders and their close kin. Others were temples where priests

or shamans lived and kept sacred paraphernalia and conducted

sacred rites. Still others were probably something like council

houses where men gathered on solemn occasion to plot revenge

or otherwise deal with crisis, as described by the Spanish

many centuries later. Unfortunately, the Caddo rarely left

many telltale clues as to what each building was used for.

They kept the buildings (and probably much of the village)

swept clean. And when an important building had served its

purpose, it was very carefully dismantled, its timbers yanked,

and everything above the floor was either burned on the spot

or taken elsewhere for disposal (or reuse). This is why we

use the purposefully vague term "special buildings"

to characterize these imposing and obviously important buildings.

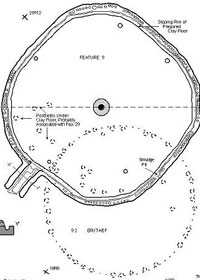

At Davis several special buildings stand apart

from all others because they are so unusual and so complicated.

Named the Ceremonial Maze by Perry Newell

and, less prosaically, Feature 35, Building F35 was uncovered

some 11 meters (36 feet) south of Mound A. Its outline is

most curious, consisting basically of three concentric, discontinuous

wall trenches, one of which was partially offset from the

others. An apparent extended entranceway faced north and there

was a hearth in the center of the building. Strangely, the

innermost trenches and two of the exterior ones had no evidence

of posts. All the other trenches had post hole patterns or the actual remains of burned posts.

The two intersecting entranceway patterns on

the north side are enigmatic. As described by Newell, they

"gave the impression that they might form an entranceway

but the narrowness of the passageway between the posts makes

this unlikely, although possible. The idea that they might

have formed two entranceways for two successive structures

seems unlikely as … the uniformity of the whole patterns

makes it appear a single unit." (From Newell and Krieger,

1949.)

We think it more likely that two building stages

are represented and that the entranceway and perhaps other

parts of the building were remodeled (and slightly reoriented)

during its life. Regardless, Building F35 is probably some

sort of religious temple, perhaps built in the shape of a

bird. Bird-shaped buildings and mounds are known elsewhere

in the Eastern Woodlands. Use your imagination and look at

the plan map of this building. Think about a turkey, a favorite

bird of the historic and the living Caddo peoples. The entranceway

at the north is the bird's neck, its wings are spread east

and west and its tail fans out to the south. Keep in mind

that you are looking at only the foundation pattern. If this

really was a bird-effigy temple, the roof, walls, and perhaps

carved wooden sculptures would have fleshed out the design,

so to speak. You might think this notion far-fetched, but

Building F35 is most definitely a strange bird.

Newell's "Ceremonial Maze" may not

be too far off the mark. We speculate that the narrow passageways

and dividers within the room may have been used for ritual

performances with costumed dancers entering from the sides

unexpectedly at key moments. The trenches lacking posts may

have been covered with wooden planks to form foot drums. If

so, lines of performers keeping beat with their feet would

have created quite an otherworldly din within the smoky and

dimly lit confines of the interior of the bird temple. Or

the drama may have unfolded on the Mound A platform overlooking

the building, an otherworldly place from which religious practitioners/performers

emerged. Whatever the actual purpose of this building, it

is unlike any other known at the site and, for that matter,

unlike any other known in the Caddo world. It was, indeed,

a "special building."

On the opposite side of Mound A was another

intriguing, if not quite as unusual, structure. Building

F9 measured about 11 meters (36 feet) across and stands

out for a number of reasons: (1) instead of being circular,

it is squared off with rounded corners (about 11 meters across;

(2) it was built with a shallow depression 14 inches deep

(other structures were built on the ground surface); (3) the

exterior wall posts were set in a trench (the posts of ordinary

houses at Davis were always set in individual holes, the wall

trench is a Mississippian technique that is uncommon in the

main Caddo Homeland, but often used in the Arkansas Basin);

(4) there were five interior posts set at regular intervals

around the circumference of the building (these may have supported

benches); (5) the floor was formed by the addition of a thin

layer of clay (prepared floors were rare at Davis); (6) the

extended entranceway was higher than the floor level; (7)

the structure was burned, yet not completely cleared away,

as was the usual practice at the site; and (8) a great many

artifacts were found within the building, most of which appeared

to have been placed there after the building was burned.

Within Building F9 were over 4,600 pottery sherds,

a piece of copper attached to a cord, fragments of three clay

pipes, a ceramic ear spool, a ceramic effigy, and various

stone tools and flint flakes. Only one other excavated Caddo

building has been found to have such an array of artifacts

near it and that is the apparent fire temple at the A.C.

Saunders site, a Late Caddo center some 57 km (35 miles) upstream

on the Neches River. While the small hearth in Building F9

does not seem to fit the notion of a fire temple, the building

was obviously something special. The purposeful depositing

of debris, including broken ritual items, suggests that is

was a conscious and presumably meaningful disposal of artifacts in the building site, perhaps following a ritual feast.

There is a better candidate for a fire temple

at the Davis site. Building 125 was uncovered about

half way between Mounds B and C. It had a simple, circular

outline about 7.4 meters (24 feet) in diameter. In the center

of the building was a deep and intensively used hearth that had

been refurbished at least twice with new clay linings. This

hearth is far more complex and intensively burned than any

other known from the site. Another unusual feature is that

four large interior posts were set at regular intervals around

the hearth, presumably to support the roof. Interestingly,

the posts were not placed on cardinal directions. This seems

to fit the early historic descriptions of the Hasinai fire

temple rather well:

The perpetual fire, the distinguishing

characteristic of the fire temple, was fed by four large,

heavy, logs arranged in cruciform pattern so that the arms

coincided with the cardinal points of the compass. In the

center of the floor, where the four logs abutted, the flame

was kept alive by feeding in small firewood from piles that

were maintained outside the structure. The ashes from the

fire were removed and were allowed to accumulate in a heap

outside. (Griffith 1954)

Special Cemetery

While is accurate to call Mound C a "burial

mound," it functioned as a special cemetery for certain

privileged ("elite") members of the Davis community

and others who were singled out to accompany the elite in

the afterlife. We are not sure where the ordinary villagers

were buried, but it was not here. This special cemetery was

established early in the site's history and periodically refurbished

and reused for the next 300-400 years. The mound itself was

built over the first pre-mound tomb as a flat-topped mound

resembling those built to serve as platforms for temples.

Once built, the mound was periodically enlarged and resurfaced,

never standing any taller than about 20 feet (6 meters). Although

the flat-topped appearance was maintained throughout its long

period of use, no trace of any crowning structure was detected

and it is likely that none was ever present.

Only about a third of Mound C was excavated,

and within this area 11 burial pits were investigated in 1968-1970

by University of Texas crews led by Dee Ann Story. It is estimated

that 15-20 burial pits remain in the unexcavated part of the

mound. While most of the pits contained no more than one individual

(or, more often,had no preserved bones), three large tombs

had multiple interments (one with eight individuals and two

with four). In contrast to the pattern at the Crenshaw site,

none of the later tombs in Mound C at the Davis site significantly

intruded into earlier tombs. (This suggests a continuity of

community, a continuity that was perhaps broken at times during the

history of the Crenshaw site.)

In the center of Mound C were relatively large

and complex tombs with elaborate grave offerings. Around the

outside of the mound and surrounding the pre-mound tomb, most

of the tombs were smaller and contained far fewer grave goods.

This pattern suggests that the most important individuals

were buried in the central area with less important people

buried in the outer mound. These "less important"

individuals were still buried in a special place in relatively

large tombs and were probably not ordinary members of the

community.

We will not discuss each of the excavated tombs

at Davis. The accompanying pictures provide glimpses of some

of the variation. Instead we will briefly describe a few contrasting

examples and then summarize some of the important patterns

and unusual finds. The special cemetery at Davis began with

the construction of a single, massive log-roofed tomb containing

eight individuals and an array of fancy grave goods. This

"log tomb" (designated Feature 134) measured

about 23 by 18 feet (7 by 5.5 meters) and was dug 11 feet

(3.5 meters) into the original earth. Two parallel rows of

three large postholes ran along the north and south walls

(long axis) of the tomb and presumably supported a low roof

only about three feet above the tomb flour. The construction

of the log tomb is inferred from stains and traces as no wood

survived.

On the floor of the log tomb were eight individuals

in extended positions (heads to the north) and neatly arranged

into four pairs. The heads of the pairs at either end were

turned to face inward toward the center of the tomb. One of

the central pairs faced toward the other central pair; the

latter includes the paramount (most important) individual

to judge from the arrangement of grave goods. Because of the

very poor condition of the bone, the age and sex of the many

of the individuals is not known. Of those that could be discerned,

most were adults 20-30 years of age and most were males, but

at least one was a female and another a child of about 6 years.

Most of the offerings were placed on the north

side of the log tomb, beyond the heads of the deceased, in

clusters or piles. Among the numerous grave offerings were

conch shell drinking cups, stone ear spools, stone celts (axe

heads), wooden objects covered in thin sheets of copper, various

patches of colored mineral pigments, effigy pipes, and arrow

points. Many of these items were of exotic materials obtained

hundreds of miles away. Interestingly, there were no pottery

vessels in this first tomb. Although there are finely engraved

vessels in some of the later tombs, these are found in small

numbers that pale by comparison to the large numbers of pottery vessels

(sometimes dozens) found in elite burials at other Caddo sites,

especially those along the Red River.

The apparent paramount individual in the log

tomb at Davis had a beaded waist belt made of marine shell

(probably whelk obtained from the Gulf coast) and an exceptionally

large, beautifully made chipped-stone knife (sword, really).

This spectacular artifact is almost certainly a prized symbol

of authority and rank. It is almost 19 inches (480 mm) long,

yet just over a half-inch thick (15 mm) at its thickest point,

making it so delicate that it was broken by the weight of

the soil when the tomb roof collapsed. It is made of an almost

white exotic chert (flint) possibly obtained in the Midwest

from the Mill Creek area of southern Illinois. Other somewhat

similar, but much smaller knives were found in the clusters

of offerings on the north side of the log tomb at Davis.

When the log tomb was sealed, the extra earth

from the pit was neatly piled around it, forming a low ring-shaped

berm. The berm was constructed in a deliberate sequence of colored

earth that was the reverse of the natural stratigraphy. In

other words, the red surface soil was placed at the bottom,

then a layer of orange soil, and finally a cap of yellow soil,

the site's deepest. The roof of the tomb was covered with

a thin layer of an unusual greenish (glauconitic?) soil, then the soil removed

from the burial pit. Enough time elapsed for the tomb's roof

to decay and collapse, spilling earth into the tomb and doubtlessly

crushing some of the skeletons and delicate offerings. The

collapsed tomb was then covered over (capped) by several layers

of fill, creating the initial flat-topped mound.

At least three burial pits were dug into and

extended below the mound at this stage. Subsequently, the

first mound was enlarged and capped by more fill layers, renewing

the flat-topped mound. More burial pits were dug from the

top and sides of this mound and then it too was renewed by

a new cap. All burial pits extended into the premound soil,

suggesting that reaching the original ground surface was ritually

important. This pattern of burial use and mound capping/addition

was repeated at total of five times over a 300-400-year period.

In contrast to the log tomb, some burial pits,

particularly those dug into the outer edges of the mound were

much smaller and did not contain many offerings. For instance,

one burial pit under the south edge of Mound C (Feature 156)

measured only about 7 by 5.5 feet and contained only a single

engraved pottery bottle. No bones were preserved, probably

because the burial pit was relatively shallow (8 feet deep)

and on the edge of the mound.

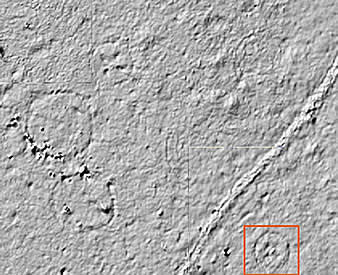

The most complicated tomb (Feature 119) was

located under the central mound. It measured about 22 by 16

feet and its floor was 16 feet beneath the mound's surface.

We can call this the "cane tomb" because

there was a layer of cane (or coppice) above the four skeletons.

(Woven cane mats or bundles of cane were probably placed on

the floors of all of the tombs.) The cane layer was the roof

or ceiling of the tomb, perhaps symbolically equivalent to

the thatched roof of a house or temple.

The four individuals buried in the cane tomb

had been arranged in extended positions in two pairs. One pair

was obviously paramount; these individuals were widely spaced

with arms outspread (the legs were not exposed by excavation),

heads placed facing up, and accompanied by high-status grave

offerings. In contrast, the other pair of individuals was

closely spaced, with arms to the sides, had few grave offerings,

and had been arranged so that the heads faced east, toward

the paramount pair.

Like the log tomb, the cane tomb had concentrations

of grave offerings on the north side of the tomb, above the

heads. There were hundreds of individual items ranging from

stream-worn pebbles (from a rattle?) and lumps of pigment

to finely engraved bottles and human effigy pipes. The artifacts

had been purposefully placed in two layers, one above and

one below the cane layer capped by a thin layer of green clay.

The paramount individuals had copper-covered wooden or stone

earspools, bone pins, a large ceremonial knife, pearl and

shell beads, traces of woven mats beneath some offerings (and

perhaps the bodies), and copper stains, one of which was once

a copper hair ornament, among other items. (Only half of the

tomb was excavated; many more offerings were probably present.)

But how do we explain the multiple skeletons?

In each tomb, the bodies were clearly interred during the

same event while the bodies were still intact, leaving us

to explain the coincidental deaths. Because of the lack of

obvious signs of warfare or disease and because the tombs

often contain individuals of different ages and different

sexes, including many young adults, we suspect that most did

not die a natural death. We suspect that the larger tombs

contain a paramount individual who died a natural death and

was accompanied by retainers or family members who were immolated

(put to death) to honor the deceased and accompany him (or

her) in the afterlife.

Such behavior is well documented in the Southeast

by archeological finds and, to a lesser degree, by early historic

accounts. In 1725, the Frenchman Le Page du Pratz witnessed

the ritual strangling of the wives, servants, and others to

accompany the deceased brother of the Great Sun, the chief

of the Natchez. Although it goes against our religious and

civil sensibilities today, other forms of human sacrifice

are well documented in prehistoric and contact period North

America as well as in Mesoamerica, most infamously among the

Aztecs (not to mention in Africa, Asia, and medieval Europe.)

In North America, slaves taken from other tribes were chosen

for sacrifice and it is possible that some or even all the

retainers in the Davis graves were slaves.

We think it more likely, however, that most of the individuals

buried in Mound C were members of the Davis community. The

repeated pattern of episodes of multiple interments can be

speculatively linked to episodes of renewal and rebuilding

at Mound A. There, evidence was found of the periodic dismantling

of special structures, followed by capping of the dismantled

buildings and the building of new structures, often of about

the same size and in the same position as the just-buried

building. Such cycles of renewal may be part of periodic ceremonies

tied to some sort of ritual or astronomical cycles or perhaps

to the deaths of paramount leaders. Unfortunately, the excavated

skeletons at Davis were poorly preserved, rendering it impossible

to make the detailed observations and comparisons that might

confirm or deny our suggestions.

Several intriguing patterns hint at the nature

and meaning of the ritual behaviors represented by the special

cemetery at Davis. The exact meanings are lost to the past,

but the repeated patterns known from the Davis site and others

are telling. One pattern is the arrangement of the skeletons

within the tombs with multiple individuals. In most cases

where the skulls were preserved, the heads of the presumed

retainers/slaves faced toward the paramount individual. The

paramount individuals had exotic artifacts obviously symbolizing

authority and high rank such as the large flint knives, stone

earspools sometimes covered in copper, shell beaded belts,

and, in two cases, polished stone staffs made of exotic greenstone

(these are often called "spuds," an unfortunate,

but memorable choice of terms). In the earlier graves most

of the offerings are piled on the north side of the tomb,

above (north of) the heads of the deceased.

Another fascinating pattern is the purposeful

selection and placement of layers of earth having certain

colors and textures. Mound C is composed of dozens of

cut and fill layers representing the digging and filling of

pits and the addition of layers capping and even repairing

the mound. Archeological trenches cut through many of these

layers and showed both how complicated the sequence of events

was and how purposeful the selection of fill was. With so

many disturbances and intrusions, one would expect the mound

fill would be jumbled and homogenized. That sometimes occurs,

but often specific layers or fills were composed only of a

certain soil with a markedly distinct color. One especially

significant earth at Davis is a green glauconitic soil that

may have been obtained from natural exposures elsewhere in

the Neches River valley (such exposures are not known to occur in

the site vicinity). A thin layer of this greenish gray soil

was placed above the high status burials and almost nowhere

else. (Newell reported finding an "altar" made of

green clay on one of the Mound A platforms, but it was poorly

documented.) The purposeful use of certain soils for certain

layers suggests that the colors and perhaps the contrasts

between colors had symbolic importance.

The very deliberate and carefully arranged patterns

represented by a single large tomb can be thought of as a

sacred scene designed to symbolize, justify, and affirm the

legitimacy, importance, and authority of the leader whose

death occasioned the tomb. Such sacred scenes may well have

embodied mythological stories such as origin myths and the

central characters in those stories. These scenes must have

reflected important Caddo icons in much the same way that

Christians use the cross and the fish, as well as biblical

characters and saints. For example, the pattern of pairs of

bodies seen in two of the tombs may relate to Caddo stories

recorded many centuries later that feature a pair of mythical

twins. According to anthropologist Robert Hall, twin-related

myths are known from many different groups in both North and

South America and may have been part of the oral tradition

of the earliest people in the New World.

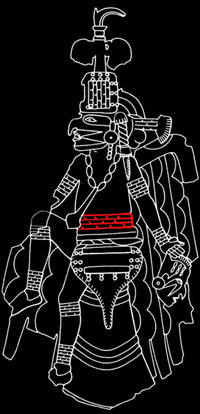

Another character common to much of the Mississippian

world is often called the Bird-Man, a central icon

in the Southern Cult or Southeastern Ceremonial Complex. The

Bird-Man is usually a human figure (male) dressed in a feathered-wing

costume with a bird mask clearly representing a raptor, probably

the peregrine falcon. Variations on the Bird-Man theme are

known from many engraved shell gorgets and drinking cups,

on copper repoussé (raised relief) plates, and occasionally

on pottery or stone artifacts from Etowah, Spiro, Moundville,

and sites in eastern Tennessee, among others. In some depictions,

the human and bird elements are combined such that the figure

is neither human nor bird. Bird-Man or Man-dressed-as-Bird,

the figure usually has arms and legs akimbo, as if dancing.

Bird-Man usually looks fierce and warlike, sometimes brandishing

weapons or grasping severed human heads. Another common element

is a wide, beaded belt around the Bird-Man's waist. In sum,

the Bird-Man is probably a mythical being associated with

conflict and power, but one that was frequently personified

in ritual dance at Mississippian centers.

The Bird-Man personification may also be represented

by several of the paramount individuals in the major tombs

at the Davis site. The clearest examples come from a massive

burial pit (Feature 118) measuring (at the top) 29 by 24 feet

(9 by 7.5 meters) and dug down about 23 feet (7 meters) from

the top of Mound C. This huge tomb contained only a single

young adult (sex not determined) resting on his or her back

with arms and feet spread out. Around the waist was a heavy

belt made of tubular conch shell beads. At the right knee

was a greenstone scepter. On either side of the head were

copper-covered stone earspools apparently fastened to one

another by a pearl-beaded band that went over the top of the

head. Four clusters of 24-40 arrow points surely represent

quivers of arrows placed around the body. The arrow points

were arranged into clusters of different types of flint (chert)

including some from central Texas and others from eastern

Oklahoma. Other offerings include bits of copper, green pigment,

shell, and possible bark cloth around the skull that may represent

some sort of headdress, a pearl necklace, and a small flint

knife. Frank Schambach thinks this individual is dressed and

positioned as the Bird-Man, a suggestion we find compelling.

Individuals in several other tombs at Davis may also represent

the Bird-Man character.

While we tend to assume that the tombs and graves

in Mound C represent burial rites following the natural (or

battle) deaths of leaders, this is hard to demonstrate. Given

all the ritual patterning and the episodic nature of destruction

and renewal cycles in Mound A, it is possible that we are

wrong and that the triggering event was not the death of some

important person. An alternative possibility that we do not

rule out is that all of the individuals interred in the special

cemetery at Davis may have been sacrificed during special

ceremonies tied to either major events in the community's

history, crises (such as severe droughts), or perhaps to celestial

events (such as the alignment of Venus and Mars or a major

eclipse). In other words, the ritual/astronomical event itself

triggered death (sacrifice), not the other way around.

Demise of the Davis Community

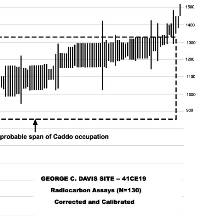

We do not know exactly when the Caddo community

who lived at the Davis site decided to move on. The community

continued into the Middle Caddo period, but was in decline

by the late13th century. The latest radiocarbon dates that

make sense suggest that some activities continued into the

14th century (early to mid-1300s), well over 450 years after

the community was established. It is clear that the abandonment

of the site was planned and orderly.

The best evidence of this is that Mounds A and

C (and probably B, although the evidence there was destroyed

by plowing) were each capped with a final layer of clay that

sealed the mounds. At Mound A, the final buildings were first

dismantled, just like earlier buildings, and then a substantial

layer of homogenous clay was added that physically capped

the mound and symbolically sealed its contents. This same

pattern has been seen at many other Caddo mound centers. When

a Caddo community abandoned a place, ordinarily they did so

with forethought and purpose.

We do not know where the community moved. One

candidate is the Washington Square site about 30 miles due

east within what is now downtown Nacogdoches, Texas. The heyday

of that site began in the mid-13th century, not long before

construction and activity at the Davis site began to wane.

Perhaps prestige and power of one ritual/political center

was eclipsed by another, as must have happened many times

in Caddo history.

Other Early and Middle Caddo Sites

Hundreds of known Caddo sites have yielded pottery

of Early and Middle Caddo styles, which are often very similar.

Some of the better-known sites are shown on the accompanying

map. Many of the same Early Caddo patterns seen at the Davis

site and the Crenshaw site are present or suspected at many

of these sites. Ritual centers, mounds capping special buildings,

buildings built on mound platforms, special cemeteries, shaft

tombs, evidence of social ranking, use of ritual items from

distant sources, and so on. Most of the Early Caddo sites

that have seen investigation are the larger sites with mounds.

We know much less about small, non-mound sites. In the next

section we take a closer look at a small Middle Caddo village

and the continued development of Caddo society.

|

Stone earspools once covered by thin

sheets of copper. These were worn covering the ears,

held in position by cords, traces of which were found

in one instance. They are only found in tombs and other

ritual contexts and were presumably worn as status symbols.

|

Drawing of Building F35, dubbed the

"Ceremonial Maze" by Perry Newell. The complicated

outline of this highly unusual and enigmatic structure

resembles that of an outstretched bird, perhaps a turkey

(some imagination required). We think it is a specialized

religious building within which religious performances

took place that may have featured dancers/characters

entering and exiting the scene through the narrow entranceway

and internal passages. The trenches lacking postholes

may have been covered by wooden planks to create floor

drums. Graphic by Dee Ann Story.

|

Building F9 was an unusual building

in many ways including its squared-off shape with rounded

corners, regularly spaced interior posts that may have

supported benches, and the mass of debris, including

broken ritual items, found on its floor. It looks like

the building was "ritually trashed" after

it was dismantled and burned. (Also visible is Building

F29, an earlier structure built and dismantled before

Building F9 existed.) Graphic by Dee Ann Story.

|

Partially excavated central hearth

in Building 125 (cross-sectioned posthole in background).

The intense burning that took place in this feature

is readily apparent. This hearth may have held a "perpetual

fire" like that in the Hasinai Fire Temples seen

by the Spanish in the late 1600s. TARL archives.

|

Mound C was a special cemetery for

certain privileged ("elite") members of the

Davis community. It was established early in the site's

history and periodically refurbished and reused for

the next 300-400 years. The deceased were placed into

burial pits (tombs) that were dug deeply beneath the

then-existing surface into the original ground. Once

built, the mound was periodically enlarged and resurfaced,

never standing any taller than about 20 feet (6 meters).

Graphic by Dee Ann Story.

|

Archeologists Elton Prewitt and Dee

Ann Story clean the floor and wall of the initial excavation

pit into Mound C in 1968. Sharp trowels were used frequently

to cut fresh exposures and trace out the complicated

layers of the earth mound. Early morning and late afternoon

lighting often revealed subtle differences that could

not be seen in the glaring mid-day sun. TARL archives.

|

Finely made arrow points were found

in several of the Mound C tombs at the Davis site. Often

they were in tight clusters suggesting that they were

originally placed in quivers made of perishable material.

TARL archives.

|

This spectacular artifact from the

log tomb at Davis is almost certainly a prized symbol

of authority and rank—a sword, really. It is almost

19" (480 mm) long, yet just over a half-inch thick

(15 mm) at its thickest point, making it so delicate

that it was broken by the weight of the soil when the

tomb roof collapsed. It is made of an almost white exotic

chert (flint) possibly obtained in the Midwest from

the Mill Creek area of southern Illinois. TARL archives.

Click to see both sides

|

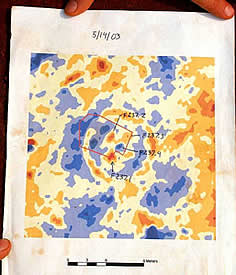

Map showing location of Feature 119,

the cane tomb, and schematic cross-section showing the

relationship of this tomb to others nearby. Notice that

none of the tombs significantly intrudes into the others.

Graphic by Dee Ann Story.

|

Cane tomb (Feature 119) during excavation,

1969. The excavation and recording of this complicated

tomb took several weeks of tedious work as each item

was carefully mapped and photographed in place before

removal. TARL archives.

|

Clusters of grave offerings along

the north wall of the "cane tomb" (Feature

119). TARL archives.

|

Cane impressions left by layer (or

coppice) of river cane that formed the roof of the cane

tomb. TARL archives.

|

Drawing of "bird-man" depicted

on a repoussé copper plate from the Etowah site,

Georgia. In this example the bird-man seems to be a

human dancer wearing a falcon costume. A human head

appears to be dangling by its scalp from the bird-man's

left hand. The bird-man also wears a tubular shell bead

waist band ( highlighted in red), very similar to that

found in tomb F18 at the Davis site.

|

Artist's depiction of the addition

of a final layer of clay to Mound A at the end of the

life of the Caddo community at the Davis site, sometime

around A.D. 1300. The clay layers physically and, ritually

sealed the mounds and the important temples and buildings

that once stood here. Painting by Nola Davis, courtesy

Texas Parks and Wildlife Department.

|

|