Unlike Las Vegas, what happens in the radiocarbon lab does not stay in the radiocarbon lab (nor should it). Like Las Vegas, having a thoughtfully conceived strategy can help a radiocarbon budget pay off to its maximum potential, or at least offset the risks inherent to the destructive process that is radiocarbon dating. This section explains the process by which most radiocarbon assays are made in an accelerator mass spectrometry (AMS) radiocarbon laboratory today: pretreatment, graphitization, radiocarbon measurement, and age calculation.

Pretreatment

The laboratory scientist begins by cleaning the radiocarbon sample, which ensures that only the sample material is assayed and not carbon-bearing contaminates (see below). Contaminates are removed by one or several of five methods: physical removal, acid extraction, base extraction, solvent extraction, and separation at the molecular level. The pretreatment method(s) selected by the technician depends on the contaminant type and the durability of the sample material.

The typical pretreatment steps for some of the most-common sample material types—wood, non-wood plant materials, and bone—are described below. Other less-frequently dated materials, like terrestrial and marine shell, hair and other keratin-based animal tissues, and residues coating artifacts (such as from inside pottery vessels) are not discussed here. See Credits & Sources for additional resources that discuss these topics.

Wood and wood charcoal are the most dated archeological materials. Past peoples had many uses for wood, such as fuel for fires and as construction material for dwellings. Charred wood survives longer than most other plant remains in archeological deposits, and the strong cellular structure of wood withstands rigorous pretreatment. A typical first step in pretreating wood samples is to remove visible contaminants like rootlets which grew around or through the sample material. Larger rootlets can be removed with tweezers. Strong chemical washes are also used to remove smaller rootlets but may reduce sample size by up to 40%.

Soil humics (humic and fulvic acids) are another common wood contaminant. Soil humics in active soil horizons can be incorporated into buried wood when carbon-rich acids are transported by groundwater through soils. Soil humics extracted from wood charcoal have been dated separately from wood, and age discrepancies between the two fractions have been found on the scale of centuries for Holocene-age wood, and millennia in Pleistocene-age wood. In other words, samples contaminated with humics yield erroneous dates. The abundance of soil humics varies with depositional environment—organic-rich environments result in higher levels of contamination. Humic acids are soluble in base washes, and fulvic acids are soluble in acids and bases. Wood is typically treated with an acid-base-acid sequence to remove humics, with sterile water rinses between each step.

Non-wood plant materials, such as leaves, seeds, and stems, are pretreated in the same manner as wood, with a series of acid and base washes. Non-wood plant materials are often more fragile than wood, and sometimes disintegrate easily during chemical washes, so radiocarbon scientists try to be cautious when processing such samples.

Bone, like wood charcoal, is relatively abundant in the archaeological record. Bone is comprised of both organic and inorganic carbon. The organic fraction consists of proteins and lipids—chiefly collagen—the fraction typically radiocarbon dated. The inorganic fraction, apatite mineral, is easily contaminated by dissolved carbonates in groundwater which seeps into bone apatite. Because of its proclivity for contamination, bone apatite is not typically radiocarbon dated.

In the early years of radiocarbon dating, the entire bone was assayed, both organic and inorganic fractions, without pretreatment; these legacy bone dates are grossly inaccurate. Collagen extraction was pioneered by geochemist Harold Krueger in the mid-1960s, but bone pretreatment methods at that time were insufficient to remove contaminants. By the late 1980s, modern pretreatment methods and AMS technology allowed accurate dates to be obtained from small samples of bone collagen, and even from amino acids extracted from collagen. Nonetheless, dating bone sometimes still presents challenges. Most archaeological bone has little unaltered collagen, and the older the bone is, the more altered the collagen is likely to be. Pleistocene age bones, in particular, require special consideration during pretreatment because of their low organic carbon content.

During pretreatment, the exterior of the bone may be removed by abrasion or other methods and discarded. The interior bone is then typically crushed. Removal of visible contaminants, such as rootlets, may occur at the beginning of pretreatment or after the first acid step, or both. The inorganic bone apatite is removed with hydrochloric acid. The remaining organic fraction is typically then treated with sodium hydroxide to remove humic acids and other base-soluble contaminants. Sterile water rinses occur between steps.

Ultrafiltration & XAD-Purification

If amino acids are separated from collagen, processing may include removal of trace humic and fulvic acids with a resin such as XAD (name trademarked by Dow, not a known acronym), or ultrafiltration to extract the high molecular weight fraction. The high molecular weight fraction isolated during ultrafiltration is comprised of long-chain gelatins which are assumed to be higher-quality than the short-chain fraction, which also contains broken amino acids and trace humates. However, this process can result in sample sizes too small to be dated.

In contrast, XAD-purification removes trace contaminants by passing the material through XAD resin. It retains both long and short-chain gelatin fractions, resulting in a larger sample size, which makes XAD-purification well suited to obtaining accurate dates on very old bone and bone with little collagen remaining. Although XAD-purification is an expensive and likely unnecessary step for most bone samples, archeologist Jon Lohse and his colleagues have used the technique to obtain precise dates of bison bones and pin down the timing of the intermittent prehistoric periods during which bison were present in the far Southern Plains (central Texas).

Graphitization

Laboratory Subsampling

Radiocarbon labs often use only a small portion, or subsample, of the sample submitted for dating—the remainder is kept as backup. The subsample often weighs less than 0.01 gram prior to graphitization. After graphitization for AMS measurement, the same sample may weigh less than 0.001 gram (conventional radiocarbon measurement methods require much more material).

Interestingly, the more carbonized the material is already, the less sample material required; in other words, it takes a lot less wood charcoal to obtain a radiocarbon assay than it does unburned wood.

After pretreatment cleans the radiocarbon sample of carbon-bearing contaminates, graphitization removes all of the other elements from the sample, reducing it to elemental carbon. Graphitization occurs in two steps: combustion and reduction. The specific methods employed varies between labs, so this is a generalized description of the process.

During combustion, the laboratory scientist heats the sample to very high temperatures until it produces CO2 gas. The next step is reduction, during which the CO2 undergoes treatment to reduce the gaseous carbon to mineral form—graphite. The graphite is then pressed into cathodes (tiny vessels that hold individual graphite samples) for measurement by AMS or conventional methods.

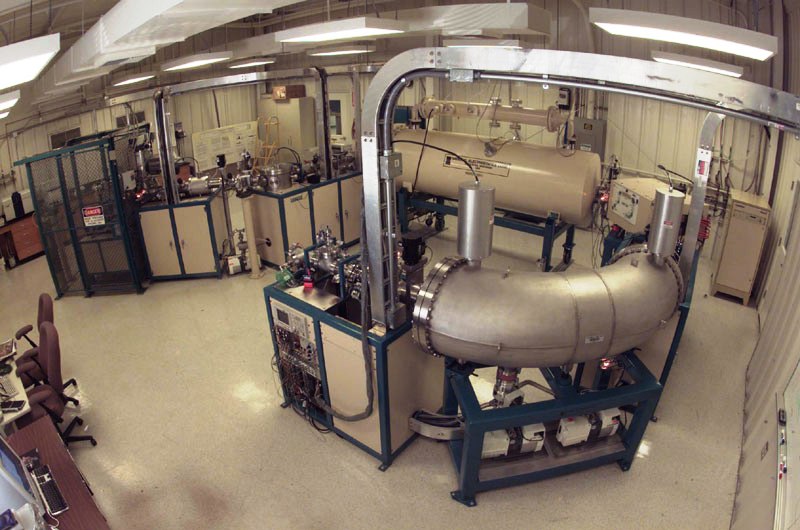

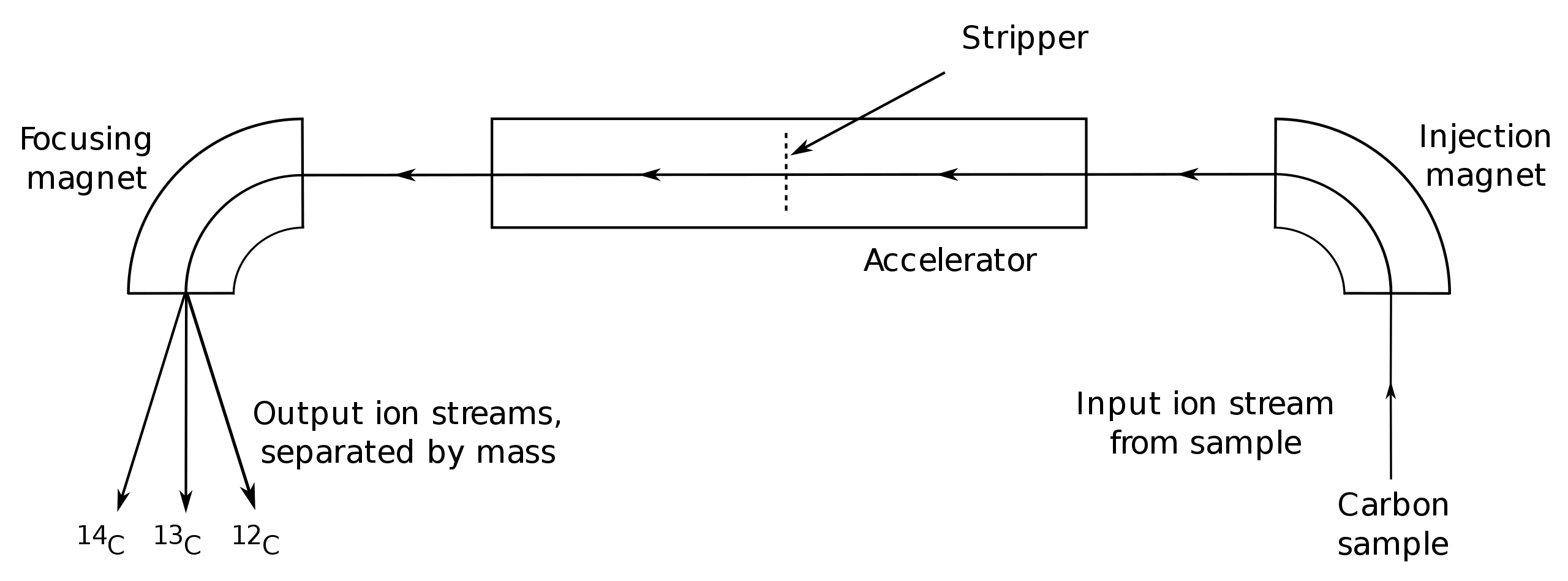

AMS Measurement

For measurement by AMS, graphite-filled cathodes are loaded into a sample wheel, which can hold dozens of cathodes in its flat face. Control cathodes are included among the sample cathodes to detect problems that might occur during various steps of the radiocarbon lab process. Controls include blanks for detecting and measuring background contamination and for quantifying isotopic fractionation that might occur in chemical pretreatment or handling, as well as "dead" graphite used to measure any background contamination and fractionation in the accelerator, and reference standards containing known levels of carbon. The cathode-filled sample wheel is then loaded into the ion source (a part of the AMS equipment), where it is bombarded by a beam of ions, usually cesium, under vacuum. The liberated carbon atoms then travel down the beamlines and into a mass analyzer, which sorts the ion beam into 12C, 13C, and 14C. The carbon isotope currents are then measured in Faraday cups. Multiple measurements may be taken on each sample cathode and a weighted average calculated.

Age Calculation

The AMS measurements made on the radiocarbon sample and on control samples are both used to calculate the radiocarbon age. The controls are used to adjust, or normalize, the measured isotope ratios. The ratio of carbon isotopes measured on the sample is used to calculate the fraction of modern carbon, or percent Modern Carbon (pMC). pMC is a ratio of carbon in the sample to the "modern" control standard (1950 AD, or year zero before present) it was processed with. The modern standard must either be oxalic acid distributed by the National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) or a sample with a precisely measured relationship to NIST-distributed oxalic acids. From pMC, the radiocarbon age is calculated. Radiocarbon labs report the conventional (normalized) age in radiocarbon years before present (RCYBP) as well as the calibrated radiocarbon date in calibrated years before present or AD/BC (cal BP or cal AD/BC).