This Plainview dart point

from Bonfire Shelter dates to about 12,000 years ago.

|

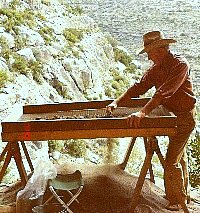

Baker Cave excavations, 1984. The

screens were placed at the edge of the rockshelter in

hopes that the updrafting winds would carry the dust

away, but at the end of the day, the archeologists were

often coated in cave dust. Photo from TARL archives.

|

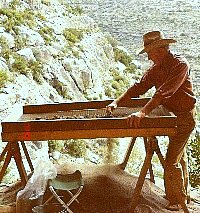

Pete Saunders found a picturesque

spot to sieve for small artifacts from the 1984 excavations

at Baker Cave. Photo from TARL archives.

|

Late Archaic dart points from the

Lower Pecos.

|

Earthenware pottery sherds from an

Infierno phase site. Photo by Steve Black.

|

Tipi or wickiup ring at an Infierno

phase site in the Lower Pecos Canyonlands. These sites are situated

at prominent points overlooking canyons and are thought

to date after A.D. 1500, perhaps representing groups

of Plains Indians. Photo by Steve Black.

|

|

Paleoindian Period (12,500 - 7000 B.C. or

14,500-8500 RCYBP). The earliest human occupations in the

region are poorly understood. The bones of extinct Ice-Age

animals found in Bone Bed I at Bonfire Shelter are thought

to show evidence of butchering, but no stone tools were documented

from this level. (See Bonfire

Shelter exhibit.) At Cueva Quebrada ("broken cave"),

burned Pleistocene mammal bones with butchering marks were

recovered in association with 10 chipped stone flakes and

a stone adze (Clear Fork tool). Charcoal from the same context

as the burned bone yielded dates ranging between 10,500 and

12,500 B.C. (12,000 to 14,300 RCYBP) The connection between

these early dates and the tools is tenuous, and very early

human occupation (pre-11,500 B.C.) of the Lower Pecos Canyonlands remains

to be confirmed.

The presence of humans in the Lower Pecos region

is well documented by 10,000 B.C. In Bone Bed 2 at Bonfire

Shelter, extinct bison bones (possibly Bison antiquus)

were recovered along with Folsom and Plainview points. (Several possible Clovis point fragments hint that Bone Bed 2 began forming even earlier.) These

animals were stampeded over a cliff into the canyon below.

On many of the bones found in the archeological deposits,

butchering marks are clearly visible. Bison antiquus

bones were also recovered from the middle levels of Cueva

Quebrada and the lowest level of Arenosa Shelter, both of

which are roughly contemporaneous with Bone Bed 2.

Around 9,500 years ago (7500 B.C.), distinct

changes in the lifeways of Paleoindian groups are reflected

in artifact changes. Dart point styles became more localized

and diverse. Numerous Angostura and Golondrina points, typical

of the late Paleoindian period, have been recovered from the

Lower Pecos Canyonlands. The large animals of the Pleistocene had become

extinct, and the Late Paleoindian economy emphasized smaller

game and more plant foods. This is best illustrated by analysis

of a well-preserved hearth dating to 7000 B.C. in Baker Cave.

The fill of this hearth contained the remains of 16 different

kinds of plants, 11 different mammals, 6 fish, and 18 reptiles.

This diverse assemblage suggests that the area was already

a semiarid savannah with plants that are typical of the modern

environment.

Early Archaic (7,000 to 4,000 B.C. or 8500-6000

RCYBP). The combination of a semiarid climate, deep canyons,

and dry rockshelters has created perfect conditions for the

best preserved records of Archaic cultures in North America.

The earliest perishable materials in the Lower Pecos date

to the latter part of the Early Archaic. Both coiled and plaited

basketry and various tool forms —including dart points,

knives, scrapers, manos, metates, and bedrock mortars—have

been documented. Lechuguilla and yucca fiber was used to make

nets, snares, and sandals. The technology of basketry and

sandal manufacture is so similar to that documented at sites

in northern Mexico that it has been suggested that Lower Pecos

groups of the period were closely related to the peoples living

to the south and west in Coahuila.

During the Early Archaic, rockshelter occupation

became widespread in the region. At Hinds Cave in Val Verde

County, specialized activity areas were well defined, including

a latrine area, a living floor made of prickly-pear pads,

grass-lined pits, and oven areas surrounded by burned rock

refuse. Dart points characteristic of the period include Early

Corner-Notched, Early Stemmed, and Early Barbed, as well as

Baker and Bandy point types.

Two types of mobile art are known from the Early

Archaic—painted pebbles and clay figurines, the latter

rare. Painted pebbles are thought to represent human figures,

usually feminine. Clay figurines have exaggerated female attributes,

but are typically headless. Burial customs during the Early

Archaic are poorly known; however, 21 individuals representing

all age groups and both sexes were recovered from Seminole

Sink, a vertical-shaft cave near Seminole Canyon.

Middle Archaic (4000-1500 B.C. or 6000-3000

RCYBP). As populations continued to grow, the people relied

more heavily on small animals and a greater variety of plant

resources. In the Lower Pecos region, the Pandale dart point

is the time marker for the onset of the Middle Archaic. A

definitive characteristic of the Early to Middle Archaic is

the use of earth ovens for plant baking. Evidence from Hinds

Cave documents the use of earth ovens with rock heating elements

to bake lechuguilla (Agave lechuguilla) and sotol (Dasylirion

texanum). This appears to indicate a shift to less-desirable

plant resources requiring more intensive labor input.

By 2000 B.C., the localized Archaic culture

of the Lower Pecos Canyonlands was quite distinctive. Population

increase is indicated by higher numbers of both "upland"

and "lowland" sites. This coincides with the appearance

of a complex, polychrome pictographic art form, termed the

Pecos River Style, which is also considered a hallmark of

the Middle Archaic in the Lower Pecos region. These pictographs

depict anthropomorphic (human-like) and animal figures resembling

deer, mountain lions, fishes, birds, humans, and many enigmatic

figures with both human and animal characteristics. The human-like

characters adorned with feathers, wings, and antlers, and

holding plants, atlatls, darts, sticks, and pouches are believed

to have been associated with shamanic rituals, and have been

specifically linked to spiritual transformation of the participants.

Recent formal analyses of Pecos River style rock art sites

have demonstrated that some represent single panels of work

depicting specific types of rituals.

Late Archaic (1500 B.C to A.D. 1000 or 3000-1200

RCYBP). The onset of the Late Archaic in the Lower Pecos Canyonlands

is marked by the return of bison into the region. This seems

to coincide with a wet period as indicated by increases in

pine and grass pollen. The most spectacular archeological

example is Bone Bed 3 at Bonfire Shelter, which contained

the bones of an estimated 800 modern bison (Bison bison).

Bison bones have been identified at other sites in the region

including Eagle Cave, Arenosa Shelter, Castle Canyon, and

Skyline Shelter. The environment of the period has been interpreted

as cooler and wetter, promoting the growth of grasslands which

allowed bison to return to the region. Some have suggested

that plains hunting groups may have migrated into the area

following the buffalo and may be responsible for the Red Linear

rock art style.

During the final millennium of the Late Archaic,

the climate apparently returned to a more arid condition,

as is implied by a decrease in grass and tree pollen and by

the disappearance of bison from archeological deposits. The

Flanders subperiod is marked by presence of the Shumla point

type. Turpin maintains that people from the plains of Coahuila

and the surrounding mountains moved into the lower Pecos River

region following the withdrawal of bison hunters.

The presence of numerous burned rock middens

both inside and outside rockshelters suggests that the Late

Archaic was a period of intensive plant baking. An analysis

of plant materials from the refuse of a roasting pit in Hinds

Cave identified 35 plant species. Although the heated rock

was primarily used to bake sotol and lechuguilla, other very

important plant resources recovered from the midden context

included prickly pear (tunas and nodes) and mesquite (beans

and seeds).

Late Prehistoric/Protohistoric (A.D 1000

to 1500 or 1300-500 RCYBP). This final prehistoric period

is marked by the appearance of arrow points and the use of

the bow and arrow. In the Lower Pecos, the earliest appearance

of arrow points occurs around 650 B.C (1380 RCYBP) at Arenosa

Shelter. Many well-excavated sites in the region do not contain

Late Prehistoric deposits, either due to changes in settlement

patterns or to destruction of upper deposits by artifact hunters.

Point types typical of the period include a variety of arrow

points including Scallorn, Perdiz, Livermore, and Toyah .

The apparent increase in the number of ring-

or crescent-shaped burned rock middens at open sites in upland

settings has been attributed to an intensification of the

use of lechuguilla and sotol. Late Prehistoric burial customs

included flexed interments, cremations, secondary disposal

in vertical-shaft caves, and cairn burials. The Red Monochrome

art style, some examples perhaps depicting bows and arrows,

may be linked to this time period.

The Infierno phase is defined by stemmed arrow

points, end-scrapers, beveled knives, and plain brownware

and bone-tempered pottery. Settlements have been recorded

only on promontories and are marked by large concentrations

of circular stone alignments interpreted as tipi rings. The

artifact assemblage is comparable to the Toyah phase of central

and southern Texas, and is interpreted as representing an

influx of outsiders coinciding with the return of bison during

a wetter period known as the Little Ice Age in Protohistoric

and early Historic times. Age estimates for the Infierno phase

of A.D. 1500-1780 are based on comparisons with other regions,

not on radiocarbon dates. The Infierno phase may represent,

as some have argued, a very late, intrusive Protohistoric

Plains culture such as that of the Apache or, alternatively,

it may simply be a late variant of the Toyah culture in the

Lower Pecos region.

Historic (500 RCYBP-Present). In 1590,

Castaño de Sosa was the first European to traverse

the Lower Pecos Canyonlands. Spanish accounts often

describe the region as uninhabited; however, illegal slaving

expeditions that preceded de Sosa's expedition may have encouraged

the Indians to avoid all contact with Europeans. A major factor

influencing our understanding of historic native populations

of the region is that frequently, the historically documented

groups ranged into southern and central Texas as well as the

Lower Pecos Canyonlands. Historic Indian groups were widely displaced

by the expansion of the Spanish frontier from the south and

by intrusions of Apache, Comanche, and their allies from the

north and west. European and Anglo-American settlement of

the Lower Pecos did not take hold until the mid to late nineteenth

century.

This Chinese porcelain rice bowl was found

in one of the laborer camps along the Southern Pacific railroad

within the Lower Pecos region. Chinese laborers were brought

from California in the early 1880s to build the railroad that

finally connected the west with the eastern portions of the

railroad in 1884. An archeological study of one of the railroad

worker camps found many artifacts connecting southwest Texas

with China. Photo from ANRA-NPS Archives at TARL.

|

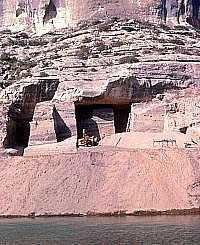

Excavations in progress at Baker

Cave, 1984. Photo from TARL archives.

|

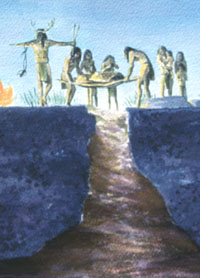

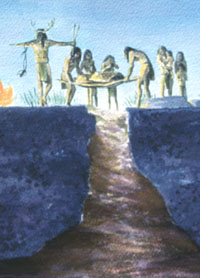

Scene showing an Early Archaic burial

ceremony at Seminole Sink as envisioned by artist Nola

Davis. Courtesy of the Texas Parks and Wildlife Department.

Original on display at Seminole Canyon State Park.

|

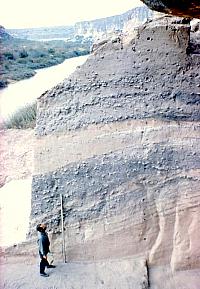

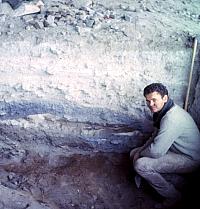

Excavations at the back of Hinds Cave. Here archeologists

have isolated a block on three sides. The profiles allowed

them to see the complex layering and guide their excavations

accordingly, layer by layer. Photo by Phil Dering. |

|

Burned Montell dart point from Bone Bed 3 at Bonfire Shelter.

This bed contained the remains of an estimated 800 buffalo,

driven off the cliff above by Late Archaic hunters. Some

think these hunters came from outside the region to the

north in the southern Plains. |

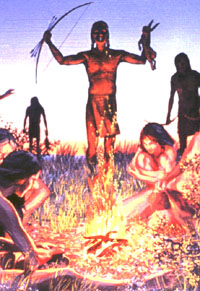

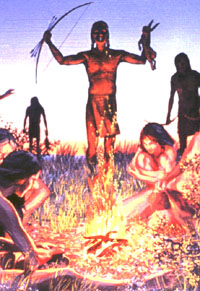

The introduction of the bow and arrow

into the Lower Pecos Canyonlands is evoked by this mural by artist

Nola Davis. Courtesy of the Texas Parks and Wildlife

Department. Original on display at Seminole Canyon State

Park.

|

The Lower Pecos Canyonlands has an interesting

variety of historic archeological sites in addition

to its many prehistoric ones. This stone-walled structure

was a homesteaders house and is located, like many Indian

sites, near a spring within a protected canyon. Photo from ANRA-NPS Archives at TARL.

|

|