The towering flower stalks of the

sotol plant are a common sight in the Lower Pecos Canyonlands. Sotol

prefers thin rocky soils and steep terrain and often

grows in great abundance in such areas. Prehistoric

peoples harvested sotol hearts or "cabezas" (heads) in quantity and baked them in earth ovens. Photo

by Phil Dering.

Click images to enlarge

|

Prickly pear cactus was used for

many purposes. The young pads (nopalitos) are edible

with minimal cooking, as are the ripe fruits (tunas).

The larger pads were used to line earth ovens to provide

moisture and keep dirt off the baked goods. Large pads

were also split open or hollowed out and used as containers.

Photo by Phil Dering.

|

Mesquite beans ripen in the late

summer and are an excellent carbohydrate source. They

require minimal cooking, but preparing the beans is

a time consuming process. The beans must be gathered

before animals can devour them and then allowed to dry

thoroughly. Dried, they must first be torn by hand into

small pieces and then pounded until the tough, almost

unbreakable, seeds can be removed. The seedless pod

fragments are then pulverized into a fine powder that

can be stored or used in a variety of ways. Photo by

Phil Dering.

|

Lechuguilla stand growing in rocky

"soil." Photo by Phil Dering.

|

Trimmed lechuguilla hearts are placed

on top of a layer of prickly pear pads in this experimental

oven. Beneath the pads are hot rocks. The pads protect

the lechuguilla from burning and add moisture. The lechuguilla

hearts will be covered with more prickly pear pads and

then a thick layer of earth. The steamy heat inside

will slowly cook the lechuguilla and break down complex,

inedible carbohydrates into simple sugars. Photo by

Phil Dering.

|

Quids, chewed lechuguilla and sotol

leaves, were found in large numbers in Hinds Cave. Lower

Pecos peoples chewed on the lower part of the baked

leaves until all the sugary carbohydrates were gone

and then discarded the leftover fibrous quids. Photo

by Phil Dering.

|

The edible parts of a baked lechuguilla

heart, like that of an artichoke, are the lower parts

of the inner leaves and the base of the plant to which

the leaves are attached.

|

|

The basic economy of the Lower Pecos Canyonlands throughout the prehistoric era was hunting and gathering

(also called foraging). Although hunting may have been the

emphasis during intervals when bison were present in the region,

as the Bonfire Shelter example clearly shows, plants probably

played a much greater role in the day-to-day survival. The

rich archeological record of the region has provided much

data for the reconstruction of prehistoric hunter-gatherer

economy in the region. The economy of the Archaic period has

been studied through the analysis of many different kinds

of materials including animal bones, plant remains, coprolites,

and human skeletal remains.

What we think of as the characteristic Archaic

economy of the Lower Pecos Canyonlands began developing at least as early

as the Late Paleoindian period. This is well illustrated by

analysis of a well-preserved hearth dating to 7000 B.C. in

Baker Cave. The fill of this hearth contained the remains

of 16 different kinds of plants, 11 different mammals (most

of them rodents), 6 fish, and 18 reptiles. This diverse assemblage

suggests that people were foraging widely and making use of

practically any creature that moved as well as many plants.

By 4,000 B.C., if not sooner, agave, yucca,

sotol, and prickly pear were used as staples, particularly

during times of subsistence stress. These were prepared in

earth ovens, the remains of which dominate the archeological

record. Nonetheless, the diet was highly varied and included

other plants, small and large mammals, reptiles, and fish.

Because large game, if available, provides more meat than

small game, one would expect evidence of large game (deer,

pronghorn, and bison) in well-preserved habitation sites in

the region. In fact, a sizable sample of bones from Hinds

Cave revealed that rodents and rabbits provided most of the

protein. In the Early Archaic burials from Seminole Sink,

the largest single regional burial population studied to date,

there was a high incidence of dental cavities, the result

of a diet very high in carbohydrates. These individuals had

even worse teeth than those of later agricultural peoples

elsewhere in North America who relied heavily on corn. Basically,

their teeth were rotten by early adulthood. Their bones also

indicate dietary trouble including severe stress caused by

periods of near starvation.

Recent experimental studies and botanical analyses

of earth ovens have demonstrated that Archaic period earth

ovens in the Lower Pecos region would have yielded only modest

quantities of food (as measured by calories) compared to the

amount of labor required. Furthermore, intensive reliance

on plant baking would have led to the quick depletion of local

lechuguilla and sotol fields, and the large quantities of

wood needed to fire the ovens would have exhausted local fuel

supplies. The tremendous amount of refuse generated by lechuguilla

and sotol processing in earth ovens created the impression

of an economy driven by plant resources that in reality do

not produce that many calories. The overwhelming archeological

visibility of earth-oven debris may have led archeologists

to overestimate group size and length of stay, and to underestimate

the degree of mobility.

Nonetheless, the remains of earth ovens are

found in almost every prehistoric archeological site in the

region. A special exhibit on earth oven cooking is being planned

for Texas Beyond History. In the meantime, here is

a quick review. All sorts of archeological terms have been

applied to earth ovens and their residue including roasting

pits, baking pits, sotol pits, mescal pits, ring middens,

crescent middens, burned rock middens, pit hearths, and large

hearths. In essence, these are all the result of earth oven

cooking. Here is how it works.

Earth ovens have been used all over the

world, in the past and even today. Although there are many

variations, the basic theme is the same. First a pit is dug.

Then wood is added and a fire is started. Rocks are placed

atop and amid the fuel. When the rocks are hot and most of

the fuel is consumed, the rocks are arranged (using long poles)

to form a flat or bowl-shaped "oven bed" (or hot

rock bed). The hot rocks form a "heating element"

which will hold and release heat for lengthy periods. The

first thing placed on top of rocks is a thick layer of green

plants such as green grass or prickly pear pads. This layer

does two things: it keeps the food from burning and it provides

the moisture needed for steam heating. Next, the food is added.

In the Lower Pecos Canyonlands this often meant the trimmed hearts or

bulbs of lechugilla and sotol. The food is covered by another

green layer, providing more moisture and also keeping the

food clean. Finally, a thick layer of earth is added that

seals in the moist heat. A properly constructed earth oven

will keep a temperature of right at 100º C (boiling temperature)

for many hours. After a long cooling period during which the

heated plants continue to cook, the earth oven is opened.

The total cooking time can be up to three days.

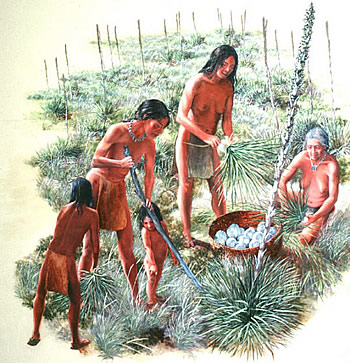

Sotol harvesting as envisioned by artist Nola Davis. (Sotol

bulbs are somewhat larger and less onion-like than depicted.)

Courtesy of the Texas Parks and Wildlife Department.

Sotol bulbs added to the hot rock bed of an earth oven

in the making as envisioned by artist Nola Davis. (Ordinarily,

a layer of green plant material would have been added first

to keep the bulbs from burning, but the finding of numerous

burnt fragments of sotol leaves suggests this step was sometimes

skipped.) Courtesy of the Texas Parks and Wildlife Department.

Cooked lechuguilla could be stored by scraping

off the sugary starches from the leaves and forming a patty

like the one shown here. Such patties are almost pure sugar,

well OK, impure sugar. Dried, these sugar cakes can be stored

for months and even longer. Photo by Phil Dering.

|

Archeologist Harry Shafer holds a

wooden digging stick found in a dry cave. Digging sticks

were probably the most important tool for Lower Pecos

peoples because they could have served many different

purposes in addition to digging.

|

Bedrock mortar holes such as these

are common in the Lower Pecos Canyonlands. Many different foods

require pulverizing, especially hard seeds and seed

pods such as mesquite beans. Photo by Phil Dering.

|

Mesquite bean processing. At top

are the seeds. At the bottom are the pieces of the bean

pods before initial pounding. In the middle row, from

left to right, are the seed husks, the partially pulverized

powder, and the fine mesquite flour. Photo and experimental

work by Phil Dering.

|

Lechuguilla is one of the smallest

members of the Agave family and one of the most important

plants in the Lower Pecos Canyonlands. Its tough fibers were the

preferred material for making sandals, mats, baskets,

and many other items. Its heart or leaf base was a major

carbohydrate source. Large quantities of lechuguilla

hearts were baked in earth ovens. Recent work has shown

that lechuguilla yields more food than the same amount

of sotol, but that both plants require a tremendous

amount of labor for the return in calories. In other

words, people must have eaten these plants only when

they had no other choice. Photo from ANRA-NPS Archives

at TARL.

|

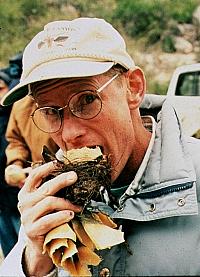

Archeologist and paleobotanist Dr.

Phil Dering chomps into

a cooked lechuguilla heart. Properly cooked, the inner

leaves and base of the plant taste sweet.

|

|