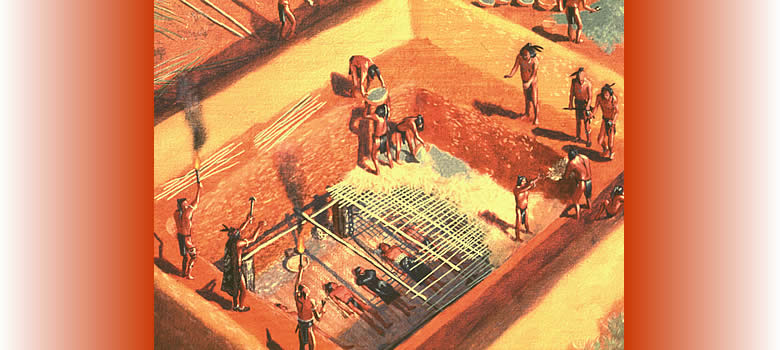

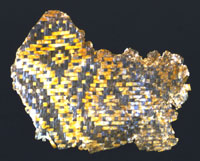

Woven mat fragment with bird design

found in a large Early Caddo tomb at the Mound Plantation

site along the Red River in northwest Louisiana. The

mat fragment was preserved only because the tomb was

waterlogged. According to early chroniclers, the Caddo

were famous for their woven mats. Deceased individuals

were often laid to rest on such mats. Courtesy Pictures

of Record.

|

Small part of the collection of a

notorious grave robber who dug up hundreds of Caddo

graves in northeast Texas. Following his death, the

looted grave offerings were sold to private collectors.

Photo from TARL archives.

|

| Caddo

ancestors were laid to rest within the Caddo Homeland

for generation upon generation. Following the accepted

burial custom of the day, grieving relatives laid each

departed Caddo in his or her grave with solemn rituals

that, in historic times, traditionally lasted six days, during the journey of the deceased to the House of the Dead in the Sky.

|

The interpretive displays at Caddo

Mounds State Historic Site (George C. Davis archeological

site) allow the public to see artifacts from graves

in context with information about many aspects of ancient

Caddo society. Courtesy Texas Parks and Wildlife Department.

|

This replica "tail-rider"

bowl was made by Caddo tribal member Jerri Redcorn based

on the original found in a grave at the Battle site

in 1912. Redcorn has almost single-handedly revived

the Caddo ceramic tradition and uses ancient Caddo pottery

as sources of knowledge. Bowl courtesy Tim Perttula.

Photograph by Sharon Mitchell.

|

Archeologists document a recently looted grave in early 1980s at the Hatchel site (part of Upper Nasoni village) on the Red River near Texarkana. The uncontrolled digging apparently had been done with the permission of the landowner. (The present landowner of this site does not allow grave robbing.) Photo courtesy Texas Historical Commission.

|

|

Caddo ancestors were laid to rest within the

Caddo Homeland for generation upon generation. Following the

accepted burial custom of the day, grieving relatives laid

each departed Caddo in his or her grave with solemn rituals

that, in historic times, traditionally lasted six days,during the journey of the deceased to the House of the Dead in the Sky. Often

the custom included burying the dead with special artifacts

or offerings, especially beautifully decorated pottery vessels,

but also with shell ornaments and other items symbolizing

their role in society and other things as well. Since Late

Woodland times, over 1200 years ago, Caddo people were buried

soon after death in a manner that archeologists describe as

primary interments. Typically, the deceased were laid out

on their backs in a fully extended position, a single individual

in each grave. In contrast, in many areas of the Eastern United

States (including the Arkansas Basin) the deceased were placed

in charnel houses where priests defleshed

the bones and stored them for months or even years. In such

societies, the stored remains were periodically gathered and

buried in ossuaries, large communal graves, as secondary interments,

as part of communal rituals. Craig Mound at Spiro is an extraordinary

example of a complex mortuary facility.

In prehistoric and early

historic times, the offerings and burial rituals for important

Caddo leaders were very elaborate, representing major expenditures

of effort and wealth apparently thought to befit the leader's

exalted position in society. Sometimes leaders were buried

in deep tombs dug through mounds and into the original earth,

perhaps symbolically connecting sacred times past with the

departed. At other times leaders were buried among their people,

but even then their graves were set apart by size, location,

and offerings. Ordinary Caddos had less elaborate graves and

were often buried in family cemeteries and sometimes (especially

children) buried beneath the floors of their houses. These

differences are just a few of those that could be mentioned;

Caddo burial practices were somewhat different from group

to group and they changed over time.

We know this because grave

robbers, farmers, archeologists, and construction bulldozers

have been digging up Caddo graves for over a century, a fact

that causes great pain to many Caddo people today. If

it were the graves of your ancestors that were subject to this distruction, you would understand

how the Caddo feel: violated, disrespected, and very sad.

There is no easy way to explain what has happened or why and

no way to reconcile all the conflicting views on the subject

of Caddo graves.

Since the early 1900s archeologists

have sought out and excavated Caddo graves, most of which

faced imminent destruction by looters, farming, and natural

erosion. The graves, skeletal remains, and associated offerings

have provided critical knowledge about the Caddo past. For

example, information on social organization, health, and disease

based on Caddo graves is not otherwise obtainable from archeological

evidence. The way a society treats its dead says much about

that society, and clearly there is no other comparable source

of information for prehistoric societies. In addition, physical

remains are practically the only source of information on

individual lives of ancestral Caddo people, as well as on the

biological relationships among individuals and populations.

Unfortunately, for many decades archeologists

treated Caddo graves with little awareness of the feelings

of living Caddo peoples. Taking a Western scientific perspective,

archeologists regarded human remains and grave offerings as

mere evidence, perhaps important evidence, but evidence nonetheless.

In this view, the remains are considered dispassionately and

treated like any other fragile and potentially important kind

of artifact. With that attitude, most archeologists had no

interaction with the Caddo Nation because they really did not appreciate

the connection between the ancient Caddo and the living

Caddo.

Part of the problem was that, by the 20th century,

very few Caddo people lived in the Caddo Homeland where archeologists

were working. Unfortunately, the thought that Caddo people

living in west-central Oklahoma might still care about the

graves of their distant ancestors was just not there. To be

fair, to most archeologists the concept of "ancestors,"

as seen through western eyes, refers mainly to relatives a

family still retains memory or record of. They did not realize that in Native American eyes, ancestors of the recent

past are thought of in much the same way as ancestors of the

ancient past. This attitude was not unique to the archeologists

who worked in the Caddo area—it was widely shared by

most American archeologists. American archeologists came to

believe that many aspects of prehistoric North American were

essentially unconnected to modern tribes—too much time

and too many changes had occurred; cultural continuity had

been lost.

Archeologists saw themselves as the only ones

truly interested in the prehistory of North America and thought

that archeology was the only thing standing between ignorance

of the past and willful grave destruction. As enlightened

scientists, archeologists sincerely believed they were working

against the inevitable march of progress and against the "dark

side"—grave robbers and land development.

In truth, most people who dig up Caddo graves

are not archeologists; they are artifact collectors intent

on finding valuable things, most of all, whole pottery vessels and other funerary offerings. They

are usually called pothunters, looters, or grave robbers.

Some do have an interest in documenting what they find and

consider themselves "amateur archeologists," but

most dig up graves solely to find grave offerings. Most dig

without regard to whatever human remains they find and keep

little or no record. As a group, grave robbers are highly

secretive and rarely publish descriptions of their work and

findings. Some want the artifacts just for their own personal

collections, but increasingly the motive is greed. An intact,

finely engraved Caddo pottery vessel can bring thousands of dollars on

the antiquities market. Untold hundreds of Caddo graves have been dug up every year in this manner, at least an order of magnitude

more than the number of graves that archeologists excavate.

Today, archeologists rarely excavate Caddo graves

except in circumstances required by federal and state cultural

resource laws and/or occasioned by emergency salvage. When

archeologists encounter Caddo graves during the course of

cultural resource management projects, they routinely consult

with the Caddo Nation of Oklahoma. In contrast, grave robbing

continues apace and slows only because so many cemeteries

have already been destroyed. Still, many Caddo graves

are dug up each year by those hunting Caddo pots. Grave robbers

often trespass on private, state, or federal lands and dig

up graves surreptitiously and illegally.

Arkansas, Oklahoma, Louisiana, and Texas all have laws affording some legal protection to "unmarked graves." In Texas, these legal protections fall under the recently amended Health and Safety Code of Texas and the Texas Administrative Code. Today, most professional archeologists in Texas do hold the view that human graves, marked or unmarked, Indian or Anglo-American, historic or prehistoric, Christian or non-Christian, should be protected by law and left unmolested except when unavoidable or with particularly good cause, such as a significant research question that can only be answered by studying graves. In such cases archeologists should work with descendant communities to reach an equitable compromise between scientific and humanistic concerns. Such a compromise is not always possible.

While all Caddo people may not have the same

attitude toward the graves of their ancestors, most believe

the resting places of their ancestors are sacred and should be left undisturbed

out of respect for their memory. One of the most remarkable

things about ancestral Caddo cemeteries is that one grave rarely

intrudes into another, even in cases where the burials were

separated in time by decades or even centuries. Given the

complete absence of headstones or other durable markers, the

graves must have been marked by perishable materials, likely marker poles, that

were periodically renewed. This shows that Caddo cemeteries,

like most cemeteries in the United States today, were created

as permanent resting places that were cared for by succeeding

generations. Given this tradition, it is easy to understand

why some Caddo see grave robbing as grave robbing whether

it be done in the name of science, curiosity, or commerce.

Other Caddo see a difference and acknowledge that archeologists

have learned many things about Caddo ancestors that had been

lost. Much of the content of the Tejas exhibit you are reading

comes from archeological research.

For their part, most archeologists today realize

that science is only one perspective and that Caddo peoples

have every right to play a major role in deciding what should

happen to Caddo skeletal remains, graves, and grave offerings.

Most of the change in attitude came about after the passage

of the Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation

Act (NAGPRA). This federal law enacted in 1990 is really a

civil rights law that has had profound consequences for the

Caddo and other federally recognized Indian tribes. Essentially

NAGPRA says that human graves on federal and tribal lands

are to be protected. It also says that Native American descendants

should decide the fate of the skeletal remains, grave offerings,

and sacred objects of their ancestors that are encountered

by the federal government and held by any institution, such

as a museum, that receives federal funding. NAGPRA requires

federal agencies that administer or carry out archeological

research on federal or tribal lands to consult with the appropriate

tribes in advance of work that might disturb graves associated

with their ancestors.

The result has been that, for the first time,

the Caddo tribe has been given a say-so in what happens when

Caddo graves are encountered that fall under NAGPRA regulations.

The Caddo tribe also has the right to decide what happens

to the Caddo skeletal remains and grave offerings in museums

and repositories across the country. As a consequence, constructive

dialogues have taken place in recent years between the tribe and all of the major

agencies and organizations that are involved in archeology

in the Caddo Homeland.

NAGPRA attempts to balance the legitimate interests

of Native Americans and scientists. While the intent of the

law is clear and reasonable, the enabling regulations have

created a tedious and contentious process that sometimes pits

Native Americans against archeologists, oral tradition against

science, and one tribe against another. For instance, who

should decide the fate of the many skeletal remains and grave

offerings that cannot be definitively affiliated to a living tribe?

What happens when two tribes both claim the same grave? How

about when a scientist proposes to use destructive analytical

methods in order to determine which, if any, living tribe

can be linked to those skeletal remains?

Fortunately, things have gone relatively smoothly in the Caddo Homeland in comparison to many other places in the country. For one thing the Caddo Homeland and the archeological sites within it is well known and there are few disputes about whether a grave is associated with the tribe or not. Still, there are many issues that remain to be resolved. For instance, the Caddo Nation has not made a final decision regarding what to do with all the Caddo skeletal remains and grave offerings in museums and repositories, although they have established a reburial cemetery on their tribal land. Some say "rebury them all," but how and where? Who will pay for proper burials for so many things? Others recognize that the thousands of Caddo pottery vessels sitting on shelves represent a tremendous cultural legacy. In many cases the skeletal remains the pottery vessels once accompanied have not survived (mainly due to acidic soil conditions). Should all these objects be buried again and, in essence, removed from visible Caddo history? Some say that Caddo pottery vessels and other grave offerings should be returned to the tribe and sensitively displayed in a museum run by the Caddo. But building and running a museum takes lots of money and training. The tribe has taken positive steps in this direction with the creation of the Caddo Heritage Museum and its own Tribal Historic Preservation Office. In the end, under NAGPRA, the Caddo Nation of Oklahoma makes the final decisions on the repatriation and reburial of human remains and funerary offerings affiliated to them.

|

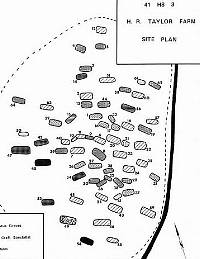

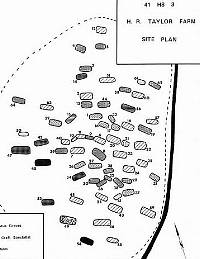

Plan of a Late Caddo community cemetery

(about A.D. 1600-1700) at the Taylor Farms site near

Lake O' the Pines within the valley of Big Cypress Creek

in northeast Texas. The University of Texas excavated

this site in 1931 and documented 64 graves. Note the

fairly consistent east-west grave orientation and the

fact that the graves do not intrude into one another.

Click images to enlarge

|

| In truth, most people

who dig up Caddo graves are not archeologists; they are

artifact collectors intent on finding valuable things,

most of all, whole pottery vessels and other funerary offerings. They are usually called pothunters,

looters, or grave robbers. |

Caddo grave offerings displayed as

trophies in the home of a notorious grave robber. Photo

in TARL archives.

|

This unusual "tail-rider"

bowl was found in a grave at the Battle site near the

Red River in southwest Arkansas in 1912 by C. B. Moore.

Such vessels resemble those found in the Mississippi

valley in northeast Arkansas and represent connections

between the two areas in Late Caddo times.

|

This Late Caddo cemetery in northeast

Texas was destroyed by looters in search of whole pottery

vessels. Broken pots and human skeletal remains were

left behind in the churned up mess.

|

| While

all Caddo people may not have the same attitude toward

the graves of their ancestors, most that we know do. They

believe the resting places of their ancestors should be

left undisturbed out of respect for their memory. |

Small, Late Caddo jar excavated from

a grave by the couple shown in picture on the left at

the Hatchel site on Red River near Texarkana. Photo

courtesy Texas Historical Commission.

|

|