|

Within the main Caddo Homeland, the

cultural continuity is unbroken from prehistory to early

history and the link to today's Caddo Nation of Oklahoma

is unquestioned.

|

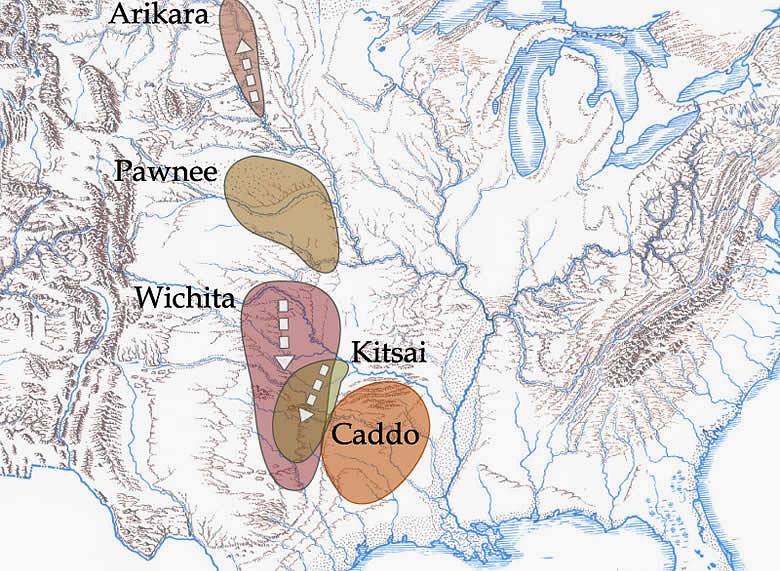

Ethnologist and famed explorer John

Wesley Powell formally defined the Caddoan language

family in 1891. Courtesy Smithsonian Institution.

|

Arikara bison-scapula hoe. This type

of tool was used in farming by main Plains groups. Smithsonian

Institution National Anthropological Archives. Click

to enlarge.

|

Walter Ross, a Wichita, ca. 1927.

Photograph by Edward S. Curtis, The North American

Indian, Volume 19.

|

Wichita grass house, ca. 1927. Photograph

by Edward S. Curtis, The North American Indian,

Volume 19.

|

"Nasutoeas, Kichai Woman, Akahedik

(Wichita)," ca. 1898. Photograph by F. A. Rinehart,

courtesy Omaha Public Library. The Kitsai (Kichai) are

the least known of the Caddoan language groups. The

Kitsai tribe no longer exists as a separate entity;

surviving members joined the Wichita in the mid-1800s.

|

Small protected buffalo herd grazing

near Wichita Mountains, southwest Oklahoma, 1908.

|

"Buffalo Bull: A Grand Pawnee

Warrior," by George Catlin, 1832. The Pawnee relied

heavily on buffalo and, in early historic times, lived

in what is today Nebraska.

|

Pawnee earth lodges and corral, Nebraska

Loup Fork Village, late 19th century. Smithsonian Institution

National Anthropological Archive.

|

Wichita Tribal center near Anadarko,

Oklahoma. Photo by Steve Black.

|

The rolling prairie in west-central

Oklahoma where the Wichita and Caddo tribes in the 1860s

were at last given small territories and allowed to

settle in peace. Photo by Steve Black.

|

Pawnee village, ca. 1875. In the

background are two massive earth lodges. Photograph

by William H. Jackson. The northernmost Caddoan groups,

the Pawnee and their close relatives the Arikara, lived

in earth lodges to survive the brutal winters of the

Central and Northern Plains.

|

|

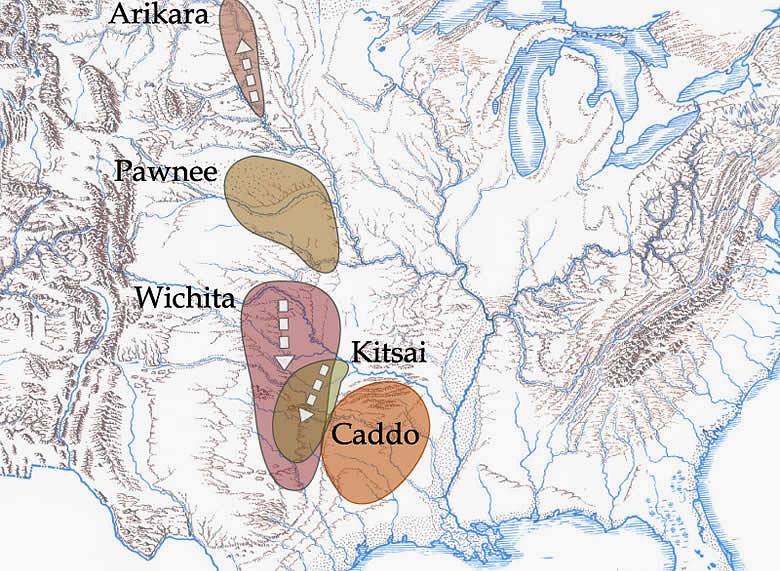

The Caddoan languages are Caddo, Wichita, Pawnee,

Arikara, and Kitsai, the latter four making up the Northern

Caddoan languages. The speakers of the Northern Caddoan languages

are also referred to as the Plains Caddoans because all four

tribes (and their various bands) lived in the Southern and

Central Plains during historic times. Caddo is the only Southern

Caddoan language.

"Caddo" vs. "Caddoan"

The words "Caddo" and "Caddoan"

have been used to mean different things by different researchers

and writers, adding considerable confusion to the complex

and often impossible task of understanding the relationships

among historic tribes and their ancestors. In the Tejas exhibits

we have tried to use these terms consistently.

In historical documents the word Caddo

is sometimes used to refer just to the Cadohadacho, but today

it is more commonly applied to all of the Caddo-speaking groups.

Although there was not a united Caddo Tribe until 1874 when,

under pressure from the U.S. government, the remnants of the

groups speaking various dialects of the Caddo language formally

joined together for survival, the term Caddo is still very

useful to refer to (1) the united Caddo Tribe; (2) all of

the groups known to have spoken Caddo dialects before 1859;

(3) the Caddo language; and (4) the direct ancestors of the

Caddo-speaking groups as inferred from archeological evidence.

Further the word is used both as a singular (i.e., the Caddo

village) and plural noun (i.e., the Caddo were corn farmers),

although the plural form, Caddos, is also used.

Fine so far: Caddo means anything to

do with the Caddo Tribe and its direct ancestors. It

is the term "Caddoan" that causes trouble. In

normal English language usage, the word can correctly be used

as the adjectival form of Caddo (i.e., the Caddoan village).

But it took on another meaning in 1891 when ethnologist and

famed explorer John Wesley Powell formally defined the Caddoan

language family. Powell, like other scholars before him, recognized

that the Caddo language was closely related to the Wichita,

Pawnee, Arikara, and Kitsai languages and, rightly, lumped

them together in one language family.

Since the 1940s, archeologists have used the

term Caddoan Area to refer to the southern and easternmost

region containing prehistoric and historic sites linked to

the ancestors of the Caddoan language family groups, although this term has fallen out of common usage. The Caddoan Area was mainly the home of the Caddo-speaking groups; however, its northern part may have been occupied in prehistoric times by some of the ancestors of certain other Caddoan groups, notably the Wichita and Kitsai. This is uncertain because the ancestors of all Caddoan language groups appear to have migrated over hundreds of miles during their histories. (Except the ancestors of the Caddo language speakers, who seem to have stayed more or less in one general area throughout their known history.) In 1542 when the De Soto entrada traveled through parts of the area, all of the Caddo groups who were encountered apparently spoke a Caddo dialect. Unfortunately, the Caddoan

Area as traditionally defined includes both the main area

that we will call the "Caddo Homeland" as well as

what is often called the "Northern Caddoan Area."

The main Caddo Homeland lies south of

the Arkansas River in the valleys and tributaries of the Ouachita,

Red, Sabine, and Neches rivers where the historically documented

Caddo speakers lived until the 19th century. This area, sometimes

referred to as the "Southern Caddo Area," has

abundant and unmistakable archeological evidence that the

direct ancestors of Caddo-speaking peoples lived there since at least A.D. 800 and probably for 3000-4000 years or longer,

perhaps much longer. In other words, within the main Caddo

Homeland, the cultural continuity is unbroken from prehistory

to early history and the link to today's Caddo Nation of Oklahoma

is unquestioned.

In contrast, the cultural continuity of the

Arkansas Basin (the so-called "Northern Caddoan

Area"), the valleys of the Arkansas River and its tributaries

and adjacent southern Ozark Highlands in northeastern Oklahoma

northwestern Arkansas, and even southwest Missouri, was broken prior to the arrival of the earliest European visitors.

This circumstance is discussed elsewhere (see "Spiro

and the Arkansas Basin"). Briefly, it is not known

whether the area was occupied by the ancestors of Caddo-speaking

peoples, the ancestors of the Kitsai, or the ancestors of the

Wichita.

The Caddoan archeological tradition clearly

represents the ancestors of the Caddo, but it may also, in

part, include archeological sites occupied by the ancestors

of the Wichita and Kitsai. In fact, as explained below, thousands

of years ago in Woodland and Archaic times it is likely that

the ancestors of all the Caddoan language family lived in

or near the Caddoan Area.

To avoid the confusion between the Caddoan language

family and the word Caddoan as the adjectival form of Caddo,

throughout the Tejas exhibits we use the term "Caddo"

to refer only to the Caddo speakers, their language, and their

direct ancestors as identified archeologically. We use the

term "Caddoan" only in the linguistic sense to refer

to the Caddoan language family.

Brief History of the Caddoan Language Family

Before modern transportation and communication

systems existed, languages spread and changed in similar,

fairly predictable ways. When a people speaking a common language

split apart, with one group migrating elsewhere and becoming

geographically isolated from the other, the "mother"

language as spoken by each group gradually changed over time.

For instance, new words may be coined, old words may be dropped,

and pronunciation changes. (Witness the differences in the

English spoken by Britains, Americans, and Australians.) The

mother language becomes two dialects that, over time, become

more and more different until eventually the speakers of one

dialect cannot understand the other. This is how new languages

form.

Linguists are the specialists who study languages

and how they relate to one another. They have worked out the

basic relationships among most of the world's surviving languages

and have classified them into various families and branches.

Linguists often use a branching tree as a metaphor for how

languages are related. English, German, Dutch, and Yiddish,

for instance, are all Germanic languages that represent the

West Germanic branch of the Indo-European language family.

Similarly, the Romance languages that developed out of Latin,

such as Spanish, French, and Italian, form the Italic branch

of the Indo-European language family.

By systematically studying how different and

similar two related languages are, linguists can estimate

how long ago they split apart, a technique called glottochronology.

Glottochronology is controversial because, among other reasons,

not all languages change at the same rate and because it is

often difficult or impossible to compare languages that are

poorly known. A great many languages have become extinct in

the last few centuries including over half the languages spoken

by Native American peoples 500 years ago. Still, studying

the relationships among languages is a powerful way of reconstructing

the early histories of different peoples across the world.

Unfortunately, the last published glottochronology

for all the Caddoan languages dates to the 1960s, before the

technique was refined. According to this estimate, the Caddoan

languages did not begin splitting apart until 3,000 to 3,500

years ago. Some Caddo archeological experts such as Timothy

K. Perttula reject this estimate and suggest that the initial

split between Southern and Northern Caddoan languages (see

below) may have taken place thousands of years earlier. That

said, as one goes back in time, confidently linking language

and ethnicity with archeological evidence is increasingly

difficult, if not impossible.

Nonetheless, the linguistic estimate is that

prior to about 3,500 years ago, the distant ancestors of all

of the Caddoan groups were a single people who spoke an ancestral

language that linguists call Proto-Caddoan. Of course,

Proto-Caddoan has long been extinct or, rather, it evolved

into the various Caddoan languages as the Proto-Caddoan ancestors

split apart and went their separate ways. It is estimated

that about 3,500 years ago (1500 B.C.) the ancestors of the

Northern Caddoan groups split from the Caddo and the two languages

began to change. Sometime after the time of Christ, the Proto-Northern-Caddoan

speakers began splitting off from one another, first the Wichita,

then the Kitsai, and finally the Pawnee. Still later, only

400-500 years ago, the Arikara split from the Pawnee.

The Caddoan languages are distantly related

to the Iroquoian languages (such as Iroquois and Cherokee)

and even more distantly related to the Siouan languages (such

as Dakota and Crow). Because of certain similarities, linguists

theorize that these three language families have had a common

origin (a shared ancestry) at some remote point in time, probably

in the central part of the country, perhaps somewhere along

the central valley of the Mississippi River. But this was

so long ago (perhaps more than 10,000 years?) that any historical

reconstruction is little more than a guess. Within the Caddoan

language family, however, we can reconstruct at least the

general patterns of movement over time.

All of the groups that spoke a Caddoan language

lived west of the Mississippi River, along its western tributaries.

During historic times the Caddoan groups were spread across

an area that spanned about 1200 miles north-south and almost

500 miles east-west. At historic contact, the latest groups

that had split off among the Northern Caddoans lived the farthest

north. The Arikara lived in what is now South and North Dakota,

while the Pawnee lived in present day Nebraska. The Northern

Caddoan groups that had split off earlier, the Witchita and

Kitsai, lived between the Pawnee and the Caddo, in what is

today Kansas and Oklahoma. Based on such geographical clues,

linguists surmise that the original homeland of the Proto-Caddoan

speakers was in the forested western fringe of the Eastern

Woodlands, within or very near what has been recognized as the Caddo Homeland.

To replay the outlines of Caddoan history, we

can guess that Proto-Caddoan ancestors lived in the Caddo

Homeland, perhaps in or near the valleys of the Red and Arkansas

rivers and the intervening Ouachita Mountatins. One group

stayed on and became the Caddo and another split off and began

moving north and west, probably up the Red and Arkansas river

systems. The Proto-Northern Caddoan speakers gradually moved

farther out onto the Plains and split apart as they moved

west and north. The ancestors of the Pawnee and Arikara moved

farther and farther north and west up the Missouri River and

its tributaries, eventually losing all memory of the Caddo.

The ancestors of the Wichita and Kichai stayed in the Southern

Plains. Nonetheless, the Caddo were separated from all of

the Northern Caddoan groups long enough ago that they had

no tradition of a common ancestry, nor could they speak to

one another.

By the end of the Plains Woodland era (about

A.D. 900), if not before, the ancestors of most (all?) of

the Northern Caddoan peoples were Plains villagers,

farmers and buffalo hunters who lived in villages scattered

through the wooded valleys across the Plains. Some archeologists

think that Caddoan-speaking groups spread westward across

Oklahoma, north Texas including the Panhandle, and Kansas,

as far as the eastern foothills of the Rocky Mountains in

what is today northeastern New Mexico and southeastern Colorado.

After A.D. 1350 in the 14th and 15th centuries, the "southwestern"

Plains villagers abandoned that area and moved north and east,

apparently in response to climatic changes and the encroachment

from the west and northwest of Apachean peoples. The ethnic

affiliations of the southwestern Plains villagers are not

known, but some archeologists believe they may have included

the ancestors of the Pawnee/Arikara and the Wichita.

In contrast with the Caddo, who stayed put in

their original homeland, all of the Northern Caddoan groups

appear to have migrated hundreds of miles during the last

two millennia. Their inferred early history makes ecological

sense. The relatively dry climate of the southern and central

Great Plains is prone to periodic drought and thus is often marginal

for dry land farming. (The western Caddoan Homeland is also

drought prone, but to a lesser extent.) And without modern

machinery and irrigation, the great grasslands of the Plains

could not be farmed. Hence the Plains villagers lived along

the relatively narrow and well-watered river valleys where

farming was possible. The bands of each group had to spread

out along the narrow valleys and were susceptible to raids

from enemy groups. Raiding and climatic change are two of

the main factors that explain why the Plains Caddoans moved

from place to place. The complex histories and migrations

of the Wichita, Kitsai, Pawnee, and Arikara peoples reflect

their precarious existence on the Plains.

Northern Caddoan Peoples

Sadly little can be said about the poorly known

Kitsai tribe (also spelled Kichai). The Kitsai language

is no longer spoken and only a bit of it was recorded before

the last Kitsai speaker passed away in the 1930s. The tribe

no longer exists as a separate entity; surviving members joined

the Wichita in the mid-1800s. The Kitsai appear to have been

farmers and hunters, like all Caddoan peoples, and are mentioned

in various French and Spanish documents. Throughout their

known history during the 18th and early 19th centuries, the

Kitsai were relatively few in number and divided into two

groups, a northern band allied with the Wichita, and a southern

band allied with the Cadohadacho and other Caddo groups. Their

known territory was in south-central Oklahoma and north-central

Texas, just west of the Caddo, especially along the Red River.

Several archeological sites in north Texas have been linked,

speculatively, to the Kitsai, including the mid-18th century

Gilbert site,

although the evidence is not compelling. Some archeologists

believe that Kitsai ancestors were the prehistoric people

of Spiro and the Arkansas Basin.

The Wichita are much better known than

the Kitsai, because they were a more numerous people, and

because they survived as a tribe. Like the Caddo, the Wichita

were made up of a number of related, but independent groups

including the Tawakoni, Yscani, Hueco, and Wichita proper,

that probably each spoke a separate dialect. The Wichita groups

(along with the remaining Kitsai) became a single tribe in

1835 when they signed a treaty with the United States. Ancestral

Wichita groups were first encountered in 1541 by Coronado's

expedition in the vicinity of the Great Bend of the Arkansas

River in present day south-central Kansas. The Spanish named

the area Gran Quivira and reported visiting a series of large

villages, some containing 200 large dome-shaped grass houses

similar to those built by the Caddo. During the historic era,

the Wichita groups moved southward through Oklahoma and into

Texas as far south as Waco, which was named after the Wichita

Hueco band whose village once stood where the city was built.

Like the Caddo, the Wichita were resettled in Indian Territory

after the Civil War and today maintain a tribal center near

Anadarko, Oklahoma.

The Pawnee and Arikara had a shared

history (i.e., were one people) until splitting apart perhaps

400-500 years ago, just before historic contact. Their ancestors

have been identified archeologically as the Upper Republican

phase of the Central Plains Village tradition in Kansas and

Nebraska. After they split apart, the Arikara moved farther

north into what is today South Dakota. Both groups lived in

earthen lodges in compact villages that were sometimes fortified.

Like other Caddoans, both groups had a mixed economy with

farming and buffalo hunting being important. The Pawnee relied

heavily on bison, while the Arikara were also fishermen as

well as traders. Prior to consolidation during the 19th century,

both the Arikara and Pawnee were made up of independent bands

speaking their own dialects. Today the Arikara remain in North

Dakota, where they settled on a reservation with the Sioux-speaking

Mandan and Hidatsa. The Pawnee have a tribal center in north-central

Oklahoma, where they were given land in 1876 in exchange for

giving up much of Nebraska.

|

"Arikara Village of Earth-covered

Lodges, 1600 Miles above St. Louis," by George

Catlin, 1832. The Arikara are the northernmost of the

groups who spoke one of the Caddoan languages. Today

they share a reservation with the Sioux-speaking Mandan

and Hidatsa in North Dakota.

Click images to enlarge

|

John Tatum, a Wichita man, and six

others, (on the left is Nasutoeas,a Kitsai woman), ca.

1898. Photograph by F. A. Rinehart, courtesy Omaha Public

Library..

|

|

Throughout the Tejas exhibits we use the term "Caddo"

to refer only to the Caddo speakers, their language,

and their direct ancestors and … "Caddoan"

only in the linguistic sense to refer to the Caddoan

language family.

|

Fred Carruth, a young Wichita man,

ca. 1898. Photograph by F. A. Rinehart, courtesy Omaha

Public Library.

|

All of the Plains Caddoan groups

depended on bison herds for food, clothing, and tools.

The Pawnee, in particular, were famed bison hunters.

Courtesy Texas Parks and Wildlife Department.

|

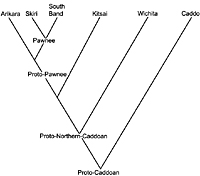

This diagram shows the relationships

among the various Caddoan languages and indicates the

order in which the various language groups are thought

to have split from one another. How long ago the various

splits occurred is very poorly known. Linguistic estimates

suggest that, prior to about 3,500 years ago, the ancestors

of all of the groups were a single people who spoke

an ancestral language that linguists call Proto-Caddoan.

About 3,500 years ago (1500 B.C.) the ancestors of the

Northern Caddoan groups split from the Caddo and the

two languages began to diversify. (Some archeologists

think the initial split may have occurred thousands

of years earlier.) Sometime after the time of Christ,

the Proto-Northern-Caddoan speakers began splitting

off, first the Wichita, then the Kitsai, and finally

the Pawnee. Still later (not long before Europeans arrived)

the Arikara split from the Pawnee and Pawnee split into

two groups.

|

Pawnee Chief Boss Sun wearing bear

claw necklace, peace medal, and holding feather fan.

Late 19th century. Smithsonian Institution National

Anthropological Archives.

|

"The Rush Gatherer," an

Arikira woman, ca. 1908. Photograph by Edward S. Curtis,

The North American Indian, Volume 5. The Arikara

were the last of the Caddoan language groups to develop,

they split apart from their close relatives, the Pawnee,

about 400-500 years ago.

|

|

|

All Caddoan groups were corn farmers

to varying degrees. Corn was more important to the Caddo

in large part because climatic conditions in the Caddo

Homeland was much more favorable to growing corn than

it was on the central Plains were the Pawnee and Arikara

lived. Photograph by Frank Schambach.

|

Kitsai Chief Knee-War-War in partial

native dress with ornaments, 1872. Smithsonian Institution

National Anthropological Archive.

|

Wichita grass house on display at

Indian City, Anadarko, Oklahoma. Photograph courtesy

Dee Ann Story.

|

Wichita grass-house ceremony, ca.

1927. Photograph by Edward S. Curtis, The North American

Indian, Volume 19.

|

|