Early Days

|

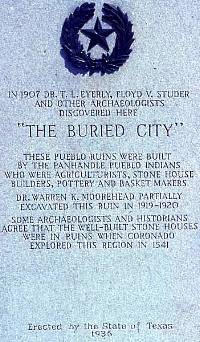

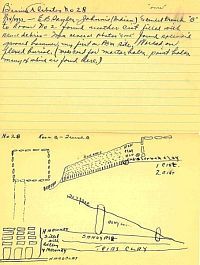

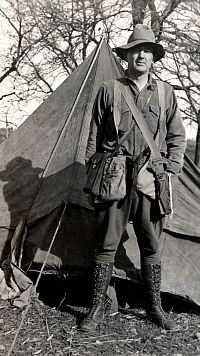

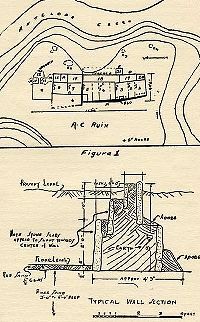

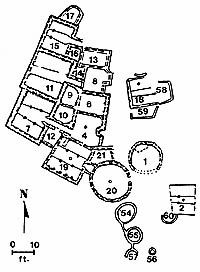

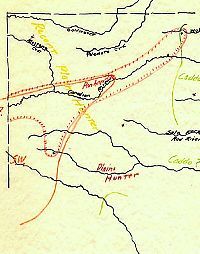

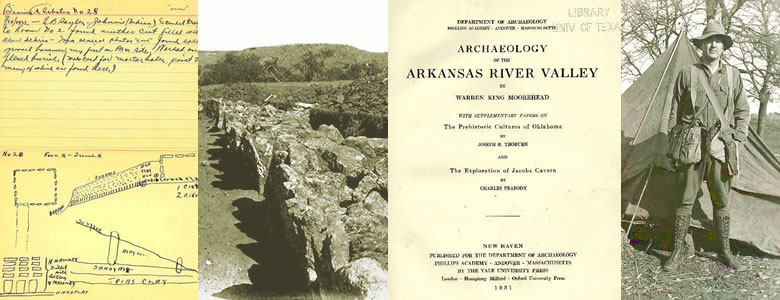

In 1907, T.L. Eyerly and his students from the Canadian Academy, a small Baptist school in the town of Canadian, explored the “Buried City” along Wolf Creek in Ochiltree County. As detailed in the Buried City exhibit, this Plains Village locality had (and still has) an impressive concentration of ruins, particularly the remains of large houses with stone foundations. Local residents had already dubbed the site the “Buried City,” a characterization that Eyerly rejected. Like Woodruff, he thought the Plains village ruins were mainly graves. During the brief Wolf Creek expedition, Eyerly and his students apparently dug into several of the buildings and probably encountered burials, giving them a false impression. The expedition was the first organized archeological investigation in Texas. Eyerly’s 1907 report on the work was the first scientific documentation of an archeological site in the state. Because of Eyerly’s reports (he published several similar accounts in different journals) and, perhaps more importantly, because of the efforts of one of Eyerly’s students, Floyd Studer, the existence of Buried City and other Plains Village sites in the Texas Panhandle began to attract national attention. Studer would become the central figure in Panhandle archeology for some 50 years. According to Studer, it was he at age 15 who had egged on his teacher, Eyerly, to mount the 1907 Wolf Creek expedition. And it was Floyd Studer’s passionate interest in Panhandle history that resulted in visits to the area by some of the leading figures in American archeology. After graduating from the Canadian Academy, Studer joined the family ranching business, got married, and served as an officer in a local bank. In 1925, he moved to Amarillo and became involved in the insurance business. He continued his life-long interest in local history by visiting every archeological site he learned about. He also wrote letters to archeologists in the major academic and research institutions in the Eastern U.S. urging them to take note of the important ruins in the Texas Panhandle, especially the Buried City. Passing references hint that he must have also sent artifact samples to some of these institutions to pique their curiosity. National and Statewide AttentionThe Buried City and other substantial ruins in the Texas Panhandle drew the interest of professional archeologists because of the area’s strategic location between the Puebloan Southwest and the Mississippian Midwestern and Southeastern United States. At the time it was widely believed that cultural developments in the Southwest were heavily influenced by the civilizations of ancient Mexico. Some authorities also thought that the Mound Builders of the Southeast and Midwest must have been influenced by prehispanic cultures in Mexico. The Southern Plains was seen as a key area where evidence of the movement of things (pottery, corn agriculture, etc.) and ideas (such as mound building) might be found. More generally, the occurrence of substantial ruins of stone architecture did not seem to match what was known about historic Plains Indians and raised many questions. Was the Panhandle area a forgotten outpost of the Puebloan Southwest? Or perhaps Pueblo culture began there before moving west? To answer such questions, prestigious scientists began visiting the Texas Panhandle and digging into the Plains Village ruins. The first was archeologist and ethnologist Jessie Walter Fewkes of the Bureau of American Ethnology at the Smithsonian Institution in Washington D.C., who paid a brief visit to Buried City in 1914 or 1915. Apparently, he dug into at least one structure and found a burial, but seems to have decided that the site paled in comparison to the more impressive ruins he was familiar with in the American Southwest. Fewkes is best known for his work at Mesa Verde, the Hopi mesas, and the Mimbres Valley in the American Southwest. Although a prolific author, he never wrote a published account of his Buried City visit. Another leading American archeologist, Warren King Moorehead, developed a more serious interest in the area. From his post as head of the Peabody Museum at Phillips Academy, a private preparatory school in Andover, Massachusetts, Moorehead launched exploratory archeological expeditions to many different areas in the Eastern United States. By 1915 he was familiar with much of the eastern United States and decided to look farther west beyond the Mississippi and beyond the territories of the Mound-Builder cultures. In 1916 Moorehead began working with Professor J. B. Thoburn of the Oklahoma Historical Society and they explored sites along the lower Arkansas River including the famous site of Spiro, the significance of which was then unknown. Recognizing that this area was still part of Mound-Builder territory, Moorehead expanded his search westward up the Arkansas and its tributaries. Moorehead probably learned of the stone ruins of the Texas Panhandle through letters from Floyd Studer and by reading Eyerly’s accounts. Although he held a prestigious post, Moorehead was largely a self-educated man obsessed since youth with archeology and American Indians. Because of his lack of formal training, he was apparently uncomfortable with the fact that American archeology was becoming dominated by professional archeologists at major universities. Moorehead depended on wealthy East Coast patrons to support his work and raising the money to explore the Arkansas Valley must have been quite a challenge. Keep in mind that few overland transportation systems had been developed in the early 20th century beyond the urban areas and railroads. These factors help explain why Moorehead’s exploration project seems to have unfolded slowly and irregularly. When he had funds, Moorehead hired assistants and sent them out. In 1917 he sent Harvard-trained archeologist Fredrich H. Sterns to Buried City to do preliminary work including excavation. Sterns had already done similar exploration in the Central Plains. Sadly, within a year Sterns and Moorehead had a falling out over who had the intellectual rights to the Buried City findings and they ended up in court battling over the field notes and artifacts. Stung by the debacle, Moorehead hired an untrained but willing explorer from Fort Smith, Arkansas, C. B. Franklin. In 1919 Franklin retraced Sterns footsteps at Buried City and also visited other sites in the eastern Texas Panhandle and western Oklahoma. Finally, in 1920 Moorehead himself excavated for three weeks at Buried City and then visited a number of other Plains Village sites in the central Panhandle, an area we today recognize as the core of Antelope Creek culture. Moorehead and his associates including Studer, who undoubtedly led Moorehead to most of the sites he visited, identified over 100 sites in the Texas Panhandle and described considerable diversity in location and architecture. Moorehead felt a sense of urgency because archeological resources were being damaged and stolen as an indirect result of oil exploration in the Texas Panhandle. Sites were recorded along Tarbox and Cottonwood creeks. Along Antelope Creek, Moorehead visited a large, multi-room pueblo-like structure, Antelope Creek Ruin 22 (named by Studer), that was to become famous. Moorehead was the first archeologist to proclaim that the Antelope Creek ruins were neither Puebloan nor Mississippian; instead, he saw them as part of the Canadian Valley or Texas Panhandle culture. He described the Texas Panhandle as an area containing important archeology where Cliff Dweller (Puebloan), Plains tribes, and Texas cultures came in to contact. After 1920 Moorehead turned his attention to the now-famous major mound sites of Cahokia (Illinois) in the Midwest and Etowah (Georgia) in the Southeast. Most of the results of his “Arkansas expedition” were not reported until 1931 when he published Archaeology of the Arkansas River Valley, which includes the edited field notes and reconnaissance maps of Floyd Studer. By then several other archeologists had led their own expeditions to the Texas Panhandle and had promptly published their results. For instance, J. Alden Mason of the University of Pennsylvania Museum led a 1929 expedition to the Texas Panhandle to explore sites along the upper Canadian. Among the sites that Mason tested was Alibates Ruin 28, another Studer site that would become famous. Mason identified a building pattern of rectangular houses with four central roof support posts and realized that the artifacts were characteristic of the Plains, while the architecture was similar to pueblos in the Southwest. Although he initially described the result as a Southwest/Plains cultural hybrid, he later argued that the culture was Plains in origin. Mason, like Moorehead, felt Texas might be the key to many important problems concerning the relationships of Mexican, Pueblo, Plains, and Southeastern Indian cultures. The year 1929 also saw the first archeological expedition in the region from a Texas university. History professor W. C. “Curry” Holden of the Texas Technical College at Lubbock (today's Texas Tech University) had begun taking groups of students to sites in the Texas Panhandle and eastern New Mexico. Holden wanted to explore the relationships among Pueblo and Plains Village sites. During the next few years he and his students carried out extensive test excavations at a series of prominent Antelope Creek sites in Texas including Tarbox Ruin, Antelope Creek 22, and Saddleback Ruin. The results were published in the Bulletin of the Texas Archeological and Paleontological Society and in several student theses. During the summer of 1932, E.B. Sayles visited the Panhandle as part of a statewide reconnaissance for the Gila Pueblo, a private research foundation headquartered in Globe, Arizona. Sayles was a native of Abilene and, with his friend Cyrus Ray, had been one of the founders of the Texas Archeological and Paleontological Society (today’s TAS) in 1928. In 1932, Sayles was a self-taught archeologist just embarking on a long professional career, most of which would be spent in Arizona and the Southwest. His reconnaissance work in Texas was an ambitious, even audacious, attempt to compare archeological sites across the state, define its prehistoric cultures, and examine the relationships between various regions. Sayles’ unpublished field notes show that he visited 21 sites in the Panhandle and carried out minor excavations at Antelope Creek 22, Alibates 28, and Saddleback Ruin. He spent the most time (four days) at Antelope Creek 22, where Curry Holden and his students had been working. Sayles dug in several places, including a trench through a circular room designated as Room A. Room A protruded from the northeast corner of the main room block and was the only large circular structure (the other large rooms were rectangular). Studer thought it was a kiva (Puebloan ceremonial room), but Sayles recognized that it was actually a residential room added late in the site's history. The day after he finished digging at Antelope Creek 22, Sayles wrote a six-page manuscript entitled "Conjectural Evolution of the Slab House of the Panhandle." This fascinating document was never published, but it is of interest to serious students. It reveals that Sayles was a keen observer who reached his own conclusions based on what he saw, "without regard to previous publications on the site." (View Sayles manuscript in pdf format.) Unfortunately, little of what Sayles learned about the Panhandle villages is discussed in his 1935 report, An Archaeological Survey of Texas. This study is largely a compilation of comparative tables, interpretive maps, and broad characterizations attempting to link a small number of historically known tribes with archeological cultures now known to span well over 10,000 years. While Sayles’ study was an impressive accomplishment, given the limited state of knowledge of the day, it had little impact on the development of Texas archeology. Still, Sayles noted the occurrence of many house ruins representing what he called a “Panhandle phase” agricultural group along the Canadian River. He cited Holden’s finds of Puebloan pottery at Saddleback Ruin to estimate the age of these sites at A.D. 1350, an estimate still regarded as falling squarely within the Antelope Creek occupation span. Thus by the mid 1930s the Texas Panhandle was archeological terra incognito no more. The existence of numerous ruins of stone-based buildings was known nationally. The full age range of the ruins was uncertain, but known to be prehistoric and at least partially contemporary with relatively late Pueblo ruins in nearby New Mexico. The relationship between the Texas Panhandle culture and the Pueblo societies of New Mexico and the Southwest was being debated. To paraphrase Curry Holden, there were three logical possibilities: (1) the Pueblo sites were older and had given rise to the Panhandle culture; (2) Panhandle culture was older and gave rise to the Pueblos; or (3) the Texas Panhandle culture developed more or less independently of Pueblo culture. Several more decades would pass before the third option became widely accepted. |

|